By Julian Lee

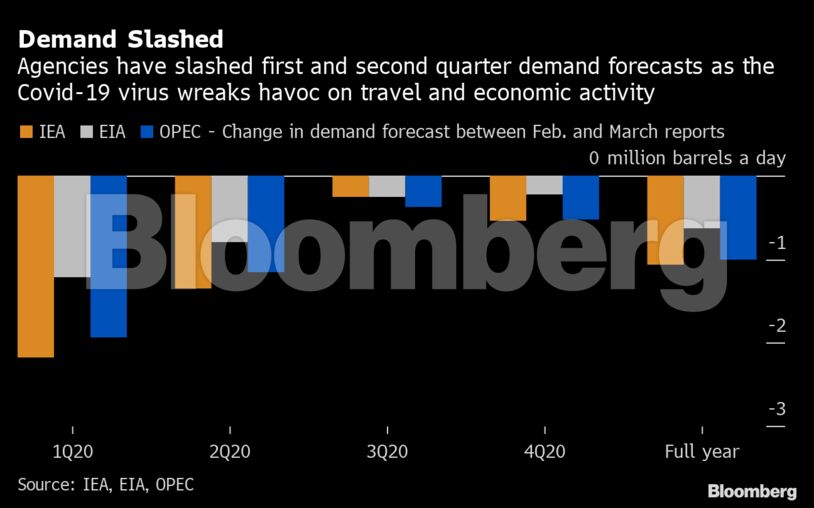

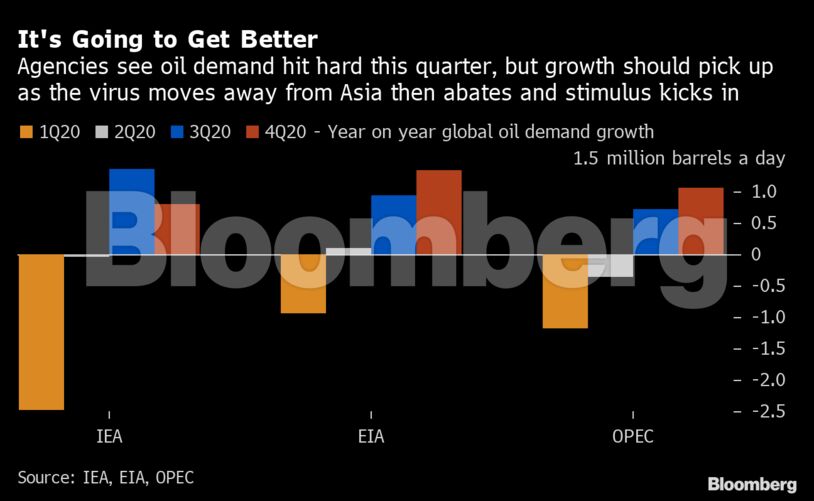

As the Covid-19 virus spreads around the world, demand forecasts have been slashed. The biggest reductions have been made to the first quarter, when the virus is likely to have its most significant impact in Asia. As the disease spreads to Europe and the Americas in the second quarter and its impact on Asia potentially eases, the effect on global oil demand is lessened, although that view may change if governments continue to respond with widespread travel bans like the one imposed by President Donald Trump on flights into the U.S. from Europe.

Forecasts of global oil demand in the first quarter of 2020 have been cut by between 1.22 million barrels a day (EIA) and 2.17 million barrels (IEA). The reductions for the second quarter show a similar pattern, with the IEA making the biggest revision and the EIA the smallest. Demand forecasts for the third and fourth quarters have also been trimmed. Although the reductions are smaller, none of the three agencies is predicting an economic rebound in the second half of the year that’s strong enough to lead them to raise their forecasts for oil demand.

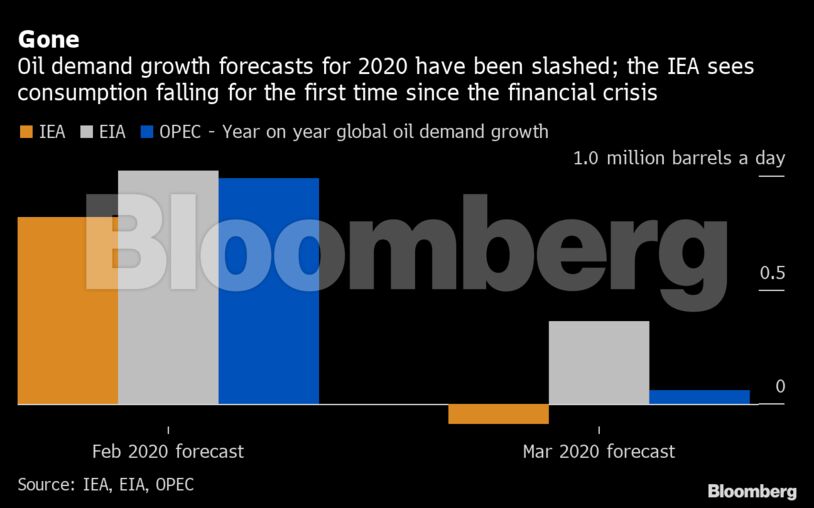

The revisions mean that year-on-year demand growth has all but disappeared. The IEA now sees the world using almost 100,000 barrels a day less oil this year than it did in 2019, while OPEC still sees demand being marginally higher than last year. The EIA is the most optimistic of the three, but even it now expects oil use to increase by just 360,000 barrels a day, down from a forecast of 1.43 million barrels in December.

The biggest hit to demand growth is seen in the current quarter and the picture is forecast to improve as the year goes on and the impact of Covid-19 is expected to weaken. Forecasts for the second quarter of the year vary between a small year-on-year increase in demand (up 90,000 barrels a day according to the EIA) and a second quarter of modest decline (down by 360,000 barrels a day according to OPEC). Growth should return to oil demand in the second half of the year, with all three agencies seeing an increase of close to 1 million barrels a day over consumption levels in the same period of 2019.

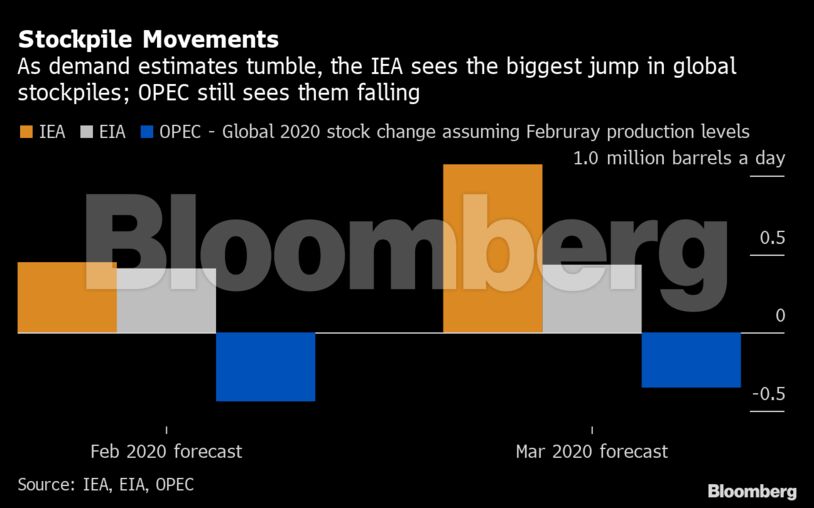

Without a corresponding cut in supply, global stockpiles are expected to swell. But instead of a cut we now look like getting a massive increase, at least in the short term. That supply surge doesn’t appear in any of the three outlooks. The EIA is the only one of the three to project OPEC production and it has it rising, but only back to the level seen in December.

In the absence of agency forecasts for oil production, we examine what would happen to global inventories if the group’s production remains flat at its most recent monthly level. For the IEA that is 28.34 million barrels a day, for the EIA 28.49 million and for OPEC: 27.77 million. The reason for the big difference between the OPEC figure and the others is that it’s the only one of the three to have removed Ecuador from the total after the country left the group in January.

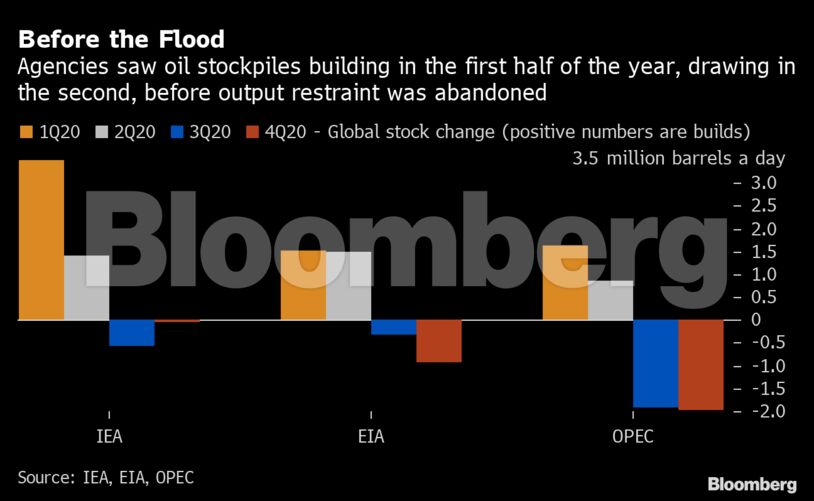

With output unchanged going forward, the IEA already saw the global stockpile building at a rate of more than 1 million barrels a day, more than double the previous month’s estimate of less than half a million barrels. OPEC on the other hand, saw stockpiles falling. Not surprisingly, given the changes to their oil demand outlooks, all three agencies expected stockbuilds in the first half of the year to be followed by draws in the second half.

The Saudi decision to abandon output restraint and flood the market with crude has made the agencies’ projections of global supply-demand balances redundant. Crude production could initially surge by as much as 4.5 million barrels a day, if announcements from Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Iraq, Nigeria and Russia are taken at face value. But lower oil prices will almost inevitably lead to a slowdown in some production elsewhere as the year progresses. These changes have not been factored into the latest outlooks from the three big agencies.

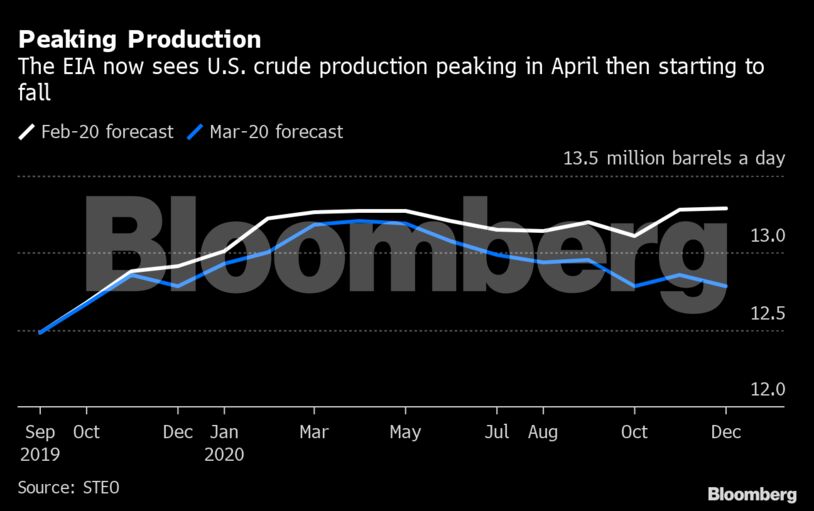

The EIA has begun to cut its forecast for U.S. crude production, which it now sees peaking as soon as April and then beginning to fall. Its latest outlook shows production in December 2020 back where it was at the end of last year. The drop could become much steeper if rival nation producers who have spare capacity begin to utilize it to the full and oil prices fail to recover from their current level near $30 a barrel.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS