The invites had been rolling in since mid-February, with titles such as “Don’t Fund Climate Disaster” and “Drop Line 3,” a reference to the name of the pipeline being funded in part by JPMorgan and built by Calgary-based Enbridge Inc. Dimon wasn’t the only executive invited—the bank’s chief risk officer, its chief operating officer and the CEO of its commercial banking arm, plus several board members, each received thousands of calendar notifications, as well.

Eventually their inboxes became so clogged up with diary dates from climate activists—not to mention the tens of thousands of emails they sent requesting the bank withdraw funding—that the bank’s IT staff intervened and the invites started bouncing back.

That the protesters’ messages could no longer get through to JPMorgan executives meant that their message had gotten through. With the bank having been sufficiently notified of their concerns, the campaigners turned their focus to America’s next largest banks, including Bank of America Corp., Wells Fargo & Co. and Citigroup Inc., as well as the heads of the biggest Canadian lenders, Royal Bank of Canada and Toronto-Dominion Bank. Their goal: to stop the flow of dollars that enable the destruction of habitats, the violation of indigenous communities and the emission of greenhouse gases.

“It is a little bit prankish,” says Alec Connon, a key organizer of the #DefundLine3 campaign that aims to persuade Enbridge’s financial backers to cut ties with the company. “Sometimes something a little creative like that can help us get the attention of very powerful people it can be hard to make pay attention.”

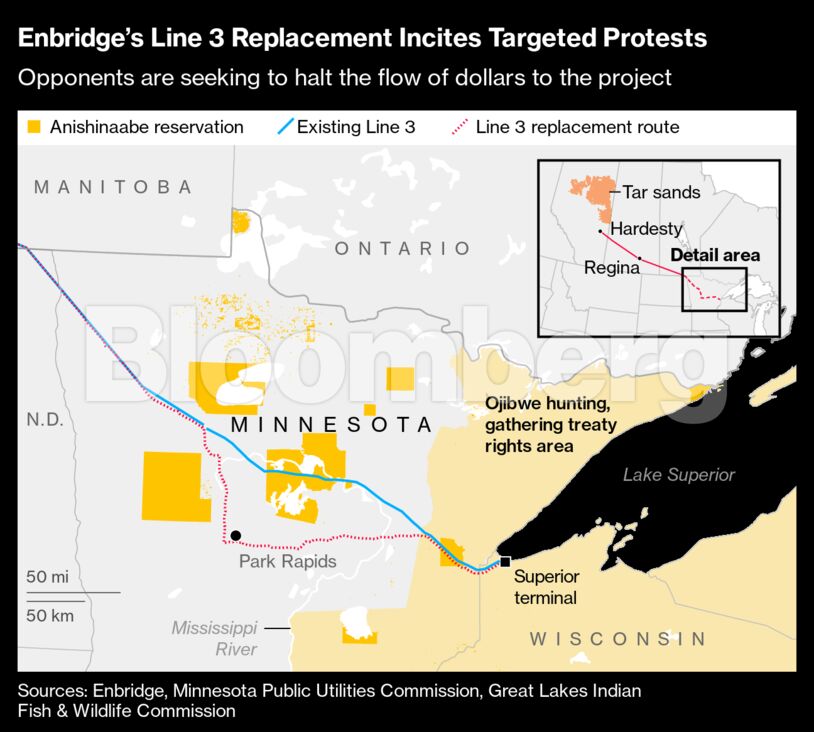

Like the Dakota Access and Keystone XL pipelines before it, Line 3 is becoming a cultural flashpoint. The new pipeline—a C$9 billion ($7.2 billion) steel tube that will transport 760,000 barrels of oil per day 1,100 miles from the tar sands of Alberta to a storage terminal in Wisconsin—will cross more than 200 water bodies, including the Mississippi River twice, as well as sensitive watersheds, ecosystems and pristine northern Minnesota landscapes. The campaign against it is also yet another chapter in the story of the U.S. and its indigenous peoples, as the pipeline will directly affect five Ojibwe tribes with treaty rights to hunt, fish and gather wild rice in the region.

Protesters say the risk of oil spills devastating waterways is too great for communities that survive off the land. Tar sands oil is also typically more carbon-intensive than other types of crude because of the extra energy required to extract and refine the sticky mixture. The #DefundLine3 campaign points to forecasts estimating that the new pipe will add 193 million tons of CO₂ to the atmosphere each year during its lifetime, more than the annual emissions of Argentina.

Enbridge emphasizes that Line 3 is a replacement for an older, existing pipeline, and that its construction was motivated by safety and maintenance concerns. “It is noteworthy that Enbridge’s pipeline has coexisted for 70 years without disturbing wild rice waters,” says Jesse Semko, a spokesperson for the company.

A spokesman for JPMorgan declined to comment on its role in financing Enbridge or its response to the activists who targeted the bank.

Bridging both the indigenous and the financial sides of the protest movement is Tara Houska. The 37 year-old Anishinaabe lawyer, a key organizer of both the on-the-ground activism and the #DefundLine3 campaign, is equally adept navigating the corridors of power in Washington and on Wall Street as she is climbing inside an unfinished pipeline in the freezing Minnesota winter and facing off against armed police in defense of indigenous lands.

That ambidexterity is key to taking on Big Oil, she says: “Make sure that you’ve got the outside game and the inside strategy at the same time.”

The seeds of #DefundLine3 efforts were planted during the Dakota Access Pipeline standoff, when Houska and other protesters were hunkered down 370 miles southwest of the Line 3 route, near the Standing Rock Indian Reservation in North Dakota.

She remembers the exact date: Oct. 27, 2016. “That was the day they had a riot line of 1,000 police officers, and tanks, and were shooting tear gas and mace and rubber bullets at our faces,” she says. “I’ll never forget that day as long as I live.”

Once state troopers and the National Guard moved in to blockade the camp—producing indelible images of cops firing water cannons at protesters in sub-zero temperatures—physically blocking the pipeline’s construction was off the table. So Houska and her fellow demonstrators started thinking about other ways to halt the project.

Yes! magazine, a nonprofit activist journal, had published an article the month before listing the banks backing the DAPL and calling on people to target them by pulling their investments and closing accounts. “It was a way for people to get involved from anywhere,” Houska says. “We essentially took that campaign and ran with it.”

As the movement gained momentum, Houska, through the Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network, began visiting banks and insurers in Norway, Switzerland, Germany and France to speak about the destruction caused by oil pipeline finance.

European lenders, including ABN Amro Bank NV and DNB ASA, stepped back from financing the project or its backers after having supported it initially, with ING Groep NV even selling its portion of a project loan supporting the pipeline. In the U.S., Citigroup’s then Chairman Mike O’Neill said “we wish we could have a do-over on this.”

Ultimately, between the protests, boycotts, legal challenges and divestment campaigns, Energy Transfer Partners, the company behind Dakota Access, and others with an ownership stake spent at least $7.5 billion on the pipeline, according to a study by the University of Colorado Law School and the Leeds School of Business—almost double initial estimates. Banks associated with the pipeline lost an additional $4.4 billion in costs.

“It was a very successful way of campaigning,” says Houska. “Following the money is finding your way to the pocketbook of a company. They do not listen to morality, but they do listen to money.”

Nevertheless, construction on DAPL finished in early 2017, and oil has been flowing through it ever since. Energy Transfer Partners spokesperson Vicki Granado says the company has been “so pleased” with the pipeline, adding that its operation brings tax revenue to states and “supports our country’s energy security and independence.”

The #DefundDAPL campaign wound up raising an army of protesters across the globe that, while temporarily down, were not defeated. In November 2019, a little over a year before #DefundLine3 would kick off, Houska and representatives from half a dozen other groups, including the Sierra Club and Greenpeace, held a gathering in Vermont to discuss ways to better align their efforts. The result was Stop the Money Pipeline, a coalition of more than 150 environmental nonprofits, which coordinates protest movements, including #DefundLine3.

Financing oil infrastructure is becoming increasingly difficult for banks and other financial institutions to justify to their shareholders, making financial institutions an especially ripe target for pipeline protests. Not only have most major U.S. and European banks, as well as some Canadian lenders, committed to reach net-zero emissions in their loan books, but the International Energy Agency said in a seminal report in May that to meet the net-zero target there should be no investment in new fossil fuel supply projects.

Since Enbridge hadn’t raised any project-specific financing for Line 3, #DefundLine3’s aim was to pressure banks not to refinance the company’s next maturing loan, a C$3 billion ($2.4 billion) revolving credit facility coming due on March 31.

Targeting a specific financial instrument is a novel approach for activists, according to Ben Cushing, financial advocacy campaign manager at the Sierra Club, which also is involved in a lawsuit against the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers aiming to revoke Enbridge’s construction permit for Line 3. Such tactics have only been used on a few previous occasions, including in late 2017 to call on Wells Fargo, JPMorgan and other funders of TC Energy Corp., the company behind the Keystone XL pipeline, not to renew two loans totaling $1.5 billion. (Michael R. Bloomberg, the founder and majority owner of Bloomberg LP, the parent company of Bloomberg News, has committed $500 million to launch Beyond Carbon in partnership with the Sierra Club.)

Such moments are opportunities for banks to decide, “do they want to double down and continue financing that kind of business? Or do they want to make a different choice and shift away from that destructive funding?,” says Cushing. “These are key moments, like a fork in the road.”

Protesters and activists started bombarding the banks with emails and calendar invites, all aimed at getting them not to refinance the loan. But what happened next surprised them. Two days after the launch of the campaign, Enbridge repaid the C$3 billion loan in its entirety and refinanced with a C$1 billion credit facility linked to sustainability targets—a type of lending that rewards consideration for climate change or the environment with lower interest payments.

The company announced the new loan in its 2020 annual report, saying that it would help align its performance on environmental, social and governance metrics with its funding costs and calling it the first such loan in its sector. Houska called it “greenwashing at its worst” in a press release, and likened giving Enbridge a sustainability loan to giving a weapons manufacturer a “peace” loan.

Greenwashing is the ultimate slur in the ESG world, yet ESG bona fides are often difficult to come by. Though banks have a legitimate role to play in helping high-carbon companies transition to less environmentally damaging ways of operating, they open themselves up to criticism when they lend to such businesses without closely supervising how those businesses are performing on relevant ESG issues.

For most of the world’s biggest banks, the de facto approach is to pledge to cut the net emissions from their office buildings and lending to zero by 2050, though often without saying how they’ll reach that target, or even how they’ll define it. That gives banks cover to show they’re responding to global warming, while at the same time leaving them plenty of latitude to continue lending to companies that are incompatible with a net-zero world.

The new credit facility is tied to ESG goals Enbridge announced last year. The company said it planned to reach net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 and reduce its emissions intensity 35% by 2030, though its targets don’t include so-called Scope 3 emissions generated by the burning of the oil it transports.

“When we announced our ESG goals, we planned on also releasing a sustainability finance strategy that links our borrowing costs to our ESG goals further incentivizing their achievement,” says Semko, the Enbridge spokesperson. He says the company has been “increasingly investing in making our own operations more sustainable for years,” including efforts to limit scope 3 emissions and backing offshore wind and solar projects, as well as tying executive and employee compensation to ESG goals.

Earlier this month, Enbridge released a framework for the issuance of sustainability-linked bonds, the first for a North American pipeline company. Sustainability-linked bonds are a nascent asset class that generally penalizes issuers with higher borrowing costs should they fail to meet certain environmental, social and governance metrics. If the issuer meets or exceeds the targets, the coupon remains unchanged.

Enbridge issued its first bond tied to ESG goals on June 24, selling $1 billion of the 12-year securities to yield 2.54%. That’s at least five basis points tighter than where the company’s regular debt would’ve been priced, thanks to the more than 100 investors who took part in the transaction, according to Max Chan, Enbridge’s vice president of treasury.

“For a company building fossil fuel infrastructure that will have a climate impact 4.5 times that of the country of Scotland to be having any type of sustainability conversations strikes me as greenwashing,” says Connon. “And any banks continuing to support this awful Line 3 tar sands project clearly need reminding that this pipeline violates any commitments they may have made on climate change.”

Construction on the new Line 3 is already complete in Canada, Wisconsin and North Dakota; work in Minnesota began in December, and is already 60% finished. A key permit for the pipeline was upheld by the Minnesota Court of Appeals in mid-June, removing a potential delay for the controversial project. Enbridge still has the suit against the U.S. Army Corps to worry about, as an adverse ruling would require the government to conduct a new environmental review. But a judge in February declined to issue an injunction until the case was decided, leaving the company free to proceed with construction. Enbridge has said it expects to finish the pipeline by the end of the year.

With their clock rapidly running down, more than a thousand protestors descended on the construction site near the headwaters of the Mississippi river in early June, Houska among them, some scaling fences and chaining themselves to equipment while others used a boat to block the entrance to an Enbridge pump station. To add further drama, a low-flying United States Customs and Border Protection helicopter sent to disperse the crowd caused a dust storm that forced demonstrators from the site. Meanwhile, activist-actor Jane Fonda and tribal leaders went on national television to lobby President Joe Biden to stop Line 3.

While the fight is far from over, either on the ground or in Washington, efforts to cut off the money spigot to Enbridge continue. The Canadian company has three further credit facilities worth a total of more than C$7 billion expiring on July 22 and July 23, and activists will make renewed efforts to call on the more than 20 banks that loaned the money, including Credit Suisse Group AG, HSBC Holdings Plc and Mizuho Financial Group Inc., not to provide further finance.

“I’d be curious to hear how a tar sands fossil fuel company is going to try to tell us, tell the public, that they are engaging in sustainable practices when they are responsible for the expansion of the fossil fuel industry,” Houska says. “I don’t think that they can slap a coat of paint on an entire body of work that involves destroying the planet.’”

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS