“The Durban climate talks have brought us to an important moment where all nations will be covered in the same roadmap toward a long-term solution for the climate crisis,” then-House Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi said at the time.

And yet this historic diplomatic breakthrough is the direct cause of the accounting confusion on display last week, when leaders of 40 nations appeared at President Joe Biden’s climate summit, each one declaring different goals, often expressed in different metrics, with different strategies, levels of domestic support, actual pollution rates, and—perhaps most confusing of all—the myriad baselines by which nations are measuring their proposed emissions cuts. By 2030:

- China intends to reduce the 2005 emissions intensity of its energy use by 60%, and India by 33% to 35%.

- The U.K. and the EU want to cut emissions 68% and 55% below 1990 levels.

- The U.S. wants to cut emissions 50%-52% below its 2005 level.

- Japan, which strengthened its target last week, wants to cut emissions 46% below its 2013 level.

- South Korea wants to cut emissions 24.4% below its 2017 level.

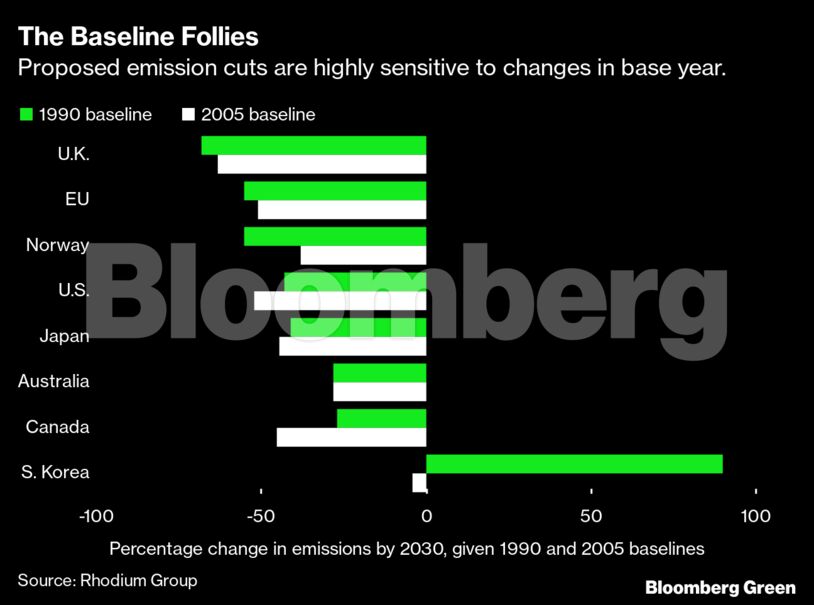

Who’s ahead in the race to cut emissions? It’s very difficult to tell when nations use different baselines.

Several factors contribute to choosing a baseline, the most important one almost certainly being which number puts a country in its best light. But there are other reasons. A 2018 report by the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change put the world on its mad-cap race to eliminate emissions. It concluded that to have a shot at limiting global warming to 1.5° Celsius, emissions must fall by about 45% below the 2010 level by 2030. Few nations have chosen that year. There’s an argument for using 1990 as the base year, which the U.K. and EU do, because it’s the original benchmark chosen in the 1990s when nations first started grappling with pollution reductions.

In the week leading up to the White House climate summit, several analysts tried to reconcile all these ad hoc numbers to try and determine how nations stand against each other. Peer pressure —the force at the heart of the Paris Agreement—won’t work if nobody can tell how anybody else is doing.

These numbers matter in global climate diplomacy and beyond. A nation’s goals might warm or cool bilateral relationships and ease or complicate finance and trade. That helps explain the lengths some nations have been going to put on their best arithmetic.

Australia in particular has earned scrutiny for Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s performance at Biden’s summit. Ketan Joshi, an analyst writing for the clean-energy and policy site RenewEconomy, called Morrison’s math “a dense bush of confusion and misdirection” that “involves twisting the numbers tracking and targeting climate action to artificially manufacture emissions reductions where there are none.” South Korea’s 2030 goal is particularly sensitive to baseline swings because of the timing of its emissions, which more than doubled since 1990.

The baseline year chosen doesn’t actually affect the amount of work a nation needs to undertake to reduce its emissions, wrote Victoria Cuming of BloombergNEF last week, “but it may be selected based on political reasons to appear more ambitious.”

If there’s any consolation in the make-your-own-accounting world, it’s that everybody wishing to slash climate risk knows the right thing to do: Whatever the stated national goal and whether or a nation has policies in place to achieve it, emissions must go down and end as a clean economy takes its place.

Eric Roston writes the Climate Report newsletter about the impact of global warming.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS