By Nathaniel Bullard

The Paris agreement is a landmark in global cooperation, and the U.S. played a significant role in making the pact happen five years ago. Now, the U.S. has essentially no role in global climate discussions, no input, and no leadership. That’s unfortunate, but more importantly for the global climate—and for global business—are the developments underway without U.S. input at all.

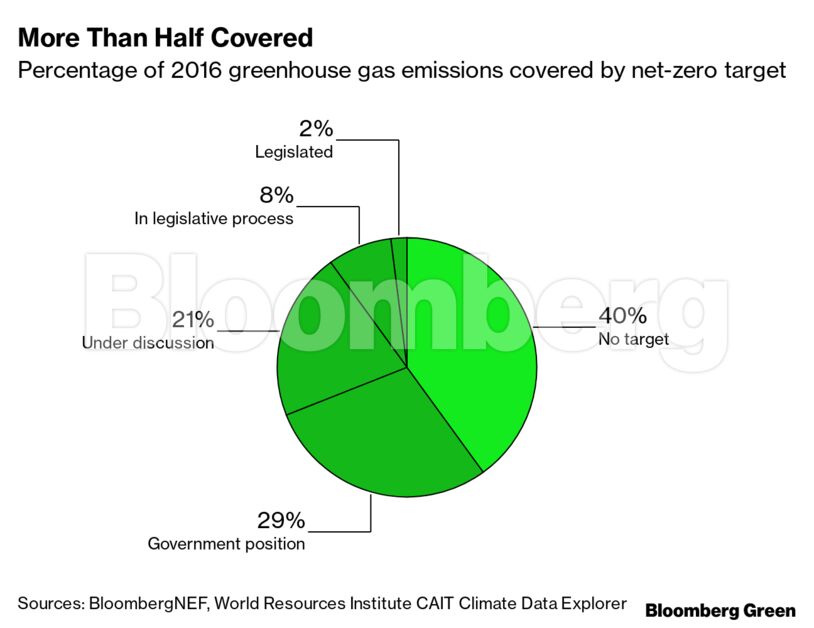

When the Paris agreement was signed, many agreements to limit emissions already existed in countries, regions, and U.S. states. None that I know of had a net-zero emissions commitment in place in 2015. Today, 60% of global greenhouse gas emissions are covered by some form of governmental net-zero commitment.

If the U.S. stays out of the Paris agreement, there will be consequences for American businesses with a global footprint, and even for some without. These consequences all stem from a simple truth: The lack of a plan to substantially (or entirely) eliminate net carbon emissions creates an unfunded liability for companies. Whether that plan is international and set by treaties and agreements or voluntary and set by a board of directors, it prepares companies for a world in which more and more governments and corporations are drawing down emissions. Climate change isn’t coming; it’s here and will have more of an impact on businesses as time goes on. Planning to limit its causes is also a way to limit its consequences—and the liabilities those consequences create.

The unfunded liability of climate inaction could undermine American companies’ global market position in a couple of ways. The first is competitive—with the world moving on in an emissions-constrained fashion, products from unconstrained U.S. companies could become unattractive. There’s a hint of that already in a the liquefied natural gas market, where French utility Engie SA has scrapped plans to buy LNG from a U.S. exporter because of the company’s environmental impact, including flared gas at production wells in Texas’s Permian Basin.

The second is financial. Where capital markets are concerned about climate, they might find U.S. companies wanting. The Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change, a European membership body representing 33 trillion euros of assets, has already urged the U.S. to recommit to Paris. U.S.-based businesses would probably benefit from continued access to global capital, which might be choked off if investors go beyond merely encouraging companies to stick to environmental commitments and start demanding it.

On top of all that, companies’ physical assets will also likely be in danger due to climate inaction. They could be imperiled by rising sea levels, rising temperatures, and more intense storms. They could also risk becoming stranded assets, designed for products that cannot be sold or targeting significantly shrunken markets.

Should it so choose, the U.S. can return to the Paris Agreement. As my colleagues Will Wade and Jess Shankleman noted, “It’s designed to be harder to leave than to join.” Leaving Paris has already created a liability for U.S. companies. The longer the U.S. is out of Paris—whether that’s just a few more months, four years, or even longer—the bigger that liability grows.

Nathaniel Bullard is a BloombergNEF analyst who writes the Sparklines newsletter about the global transition to renewable energy.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS