By Kelly Gilblom

To strike a balance, one of the strategies for the executives is to sell high-cost and high-carbon projects. But that may only offload the emissions problem on to another company.

“If one asset just passes to another and still operates at its maximum capacity, OK that may have helped the profile of that individual company, but does that actually do anything on a net effect of reduced emissions?” said Adam Matthews, the director of ethics and engagement at the Church of England Pensions Board. “That’s a legitimate question.”

Oil Sands, Coal

BP is not the only one passing on the responsibility. Royal Dutch Shell Plc divested its carbon-intensive Canadian oil-sands business in 2017 that is now operating under a new owner. Total SA sold its interest in a similar project, which was dormant, to a buyer looking to revive it. Miner Rio Tinto Plc exited coal by selling some of its assets to Glencore Plc, which plans to keep running them for years.

The companies’ actions will be discussed when hundreds of executives gather this week at the Oil & Money conference. The event, which saw noisy protests from pressure group Extinction Rebellion outside its London venue on Tuesday, will change its name to Energy Intelligence Forum next year in a nod to climate change and the energy transition.

While the asset sales help reduce costs, Dudley, Shell’s CEO Ben van Beurden and Total’s Patrick Pouyanne will also need to show they’re committed to the environment and not just offloading their responsibility.

Still, for some investors selling the high-carbon projects makes the companies more resilient to future climate legislation, and that’s a step in the right direction.

If companies can use the funds from the sale of carbon intensive projects to develop lower-intensity production, that’s a “decision that we are generally supportive of,” said Nick Stansbury, head of commodity research at Legal & General Investment Management, one of the largest shareholders of major oil companies.

Big Challenge

Oil executives say their big challenge is to cut emissions while continuing to supply energy to a growing global economy. Shutting down production can create shortages that could boost prices, reduce affordability and even encourage the start up of new projects.

Also read: Norway’s Huge New Oil Project Clashes With Growing Climate Focus

To tackle the “radical changes” required to keep global warming at a safe level, demand for low-carbon energy would have to rise dramatically, said Tal Lomnitzer, a senior investment manager at Janus Henderson Investors. It would have to be aided by government policy changes and involve social pressure, he said.

“A much faster transition is technically possible but actors need guidance,” Lomnitzer said. “It’s likely to arrive from the populace and then be expressed via bans, taxes and incentives.”

The oil companies support a tax on carbon as a way to discourage emissions, and are promoting natural gas as a cleaner fuel. France’s Total applies a carbon price internally in its assessment of projects, a spokeswoman said, as do others like BP. Qatar, the world’s biggest liquefied natural gas exporter, started a carbon capture and storage project as part of an effort to address concerns about climate change, Energy Minister Saad Sherida Al-Kaabi said Tuesday.

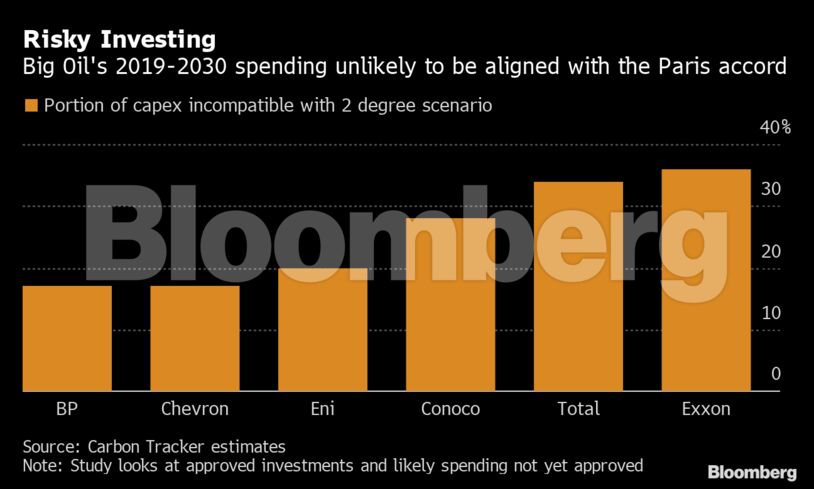

Investor pressure is also forcing the oil majors to increase spending on green energy. They’re building wind and solar projects, boosting electric-vehicle infrastructure and reducing the amount of gas they release into the atmosphere. But these investments are still a fraction of overall expenditure.

“The transition from Big Oil to Big Energy will certainly take time,” said Rob Barnett, an energy policy analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence. “But we do see things headed in that direction.”

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS