However, the EIA tracks primary energy — that is, energy before it has been transformed through combustion or chemical processes — in a meaningful way starting from the 19th century. From 1890, the first year the EIA has data on hydroelectric power, we can see a full picture of America’s energy use. We can also get a sense for where it might go in the future.

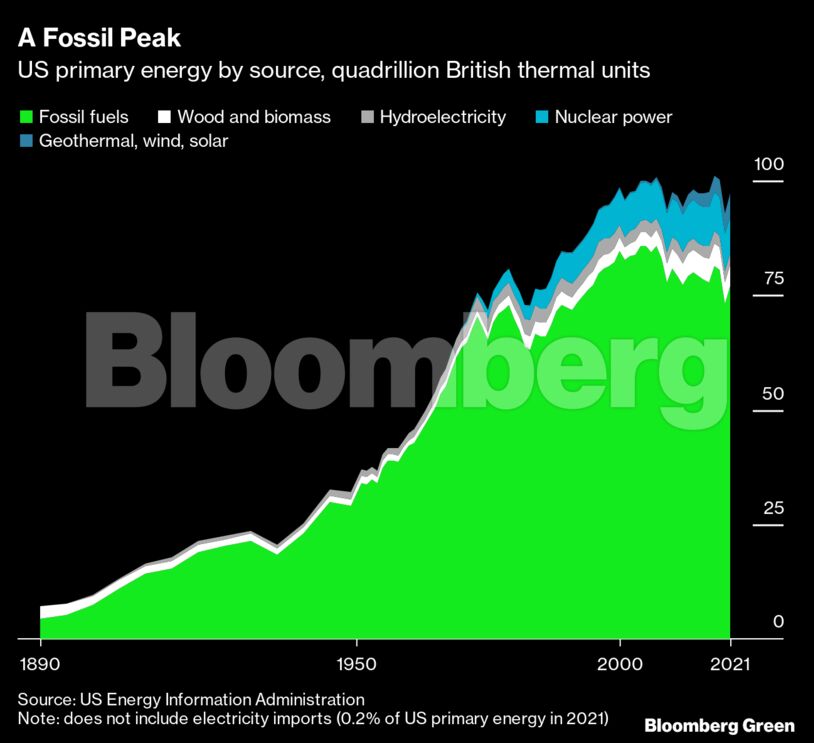

In 1890, total US primary energy consumption was just over 7 quadrillion British thermal units (quads). Last year, it was more than 90 quads. That’s an increase by about a factor of 14. For more than a century, the trend was up and up, with interruptions from wars, recessions, supply shocks and pandemics.

But then something happened in the early 2000s: Primary energy consumption hit 100 quads and stayed more or less range-bound. In 2004, it was 100.9 quads; in 2018, it hit a peak of 101.2 quads. At the same time, non-fossil sources of primary energy (hydro, wood and biomass, nuclear, geothermal, wind and solar) grew substantially.

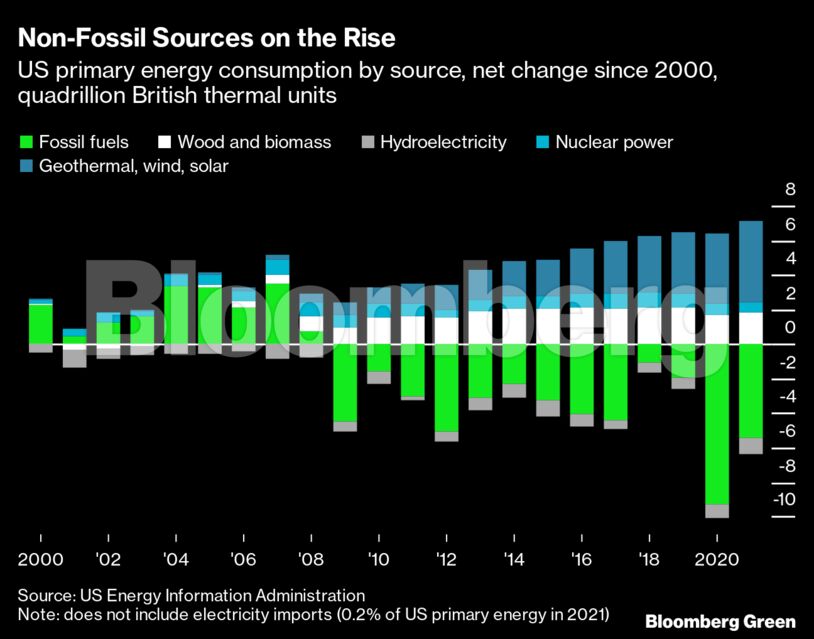

The result is a peak in fossil fuels’ contribution to primary energy in 2007, and a decline since. Nuclear adds a bit to primary energy supply; wood and biomass add a bit more, but most of the growth in supply comes from geothermal, wind and solar electricity.

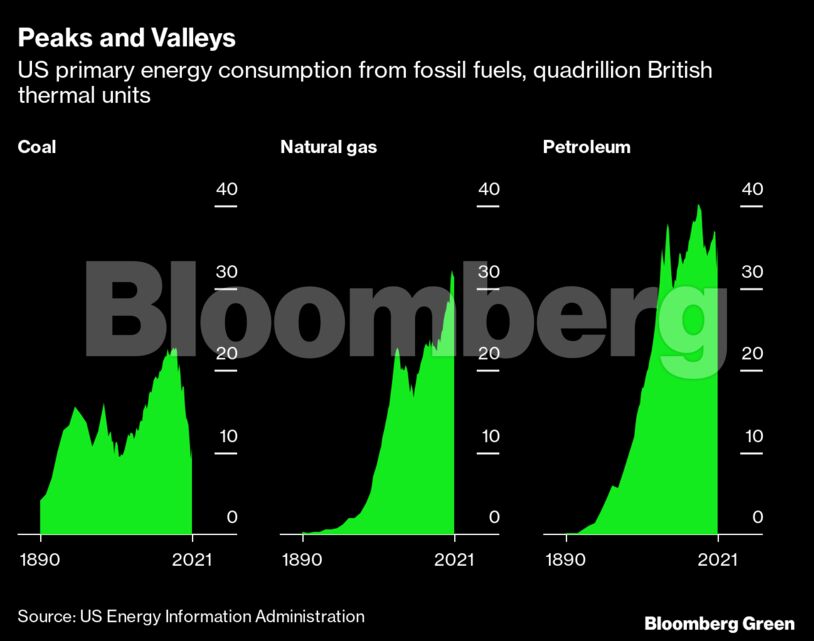

Fossil-fuel primary energy peaked in 2007, but that category is too broad to show the trend by fuel. Or rather, two trends. Coal’s contribution to primary energy peaked in 2005 and has declined by 54% since. Petroleum’s contribution peaked in 2005 as well and is down 13% since. Gas, on the other hand, surpassed coal in 2007 and has increased 39% since 2005.

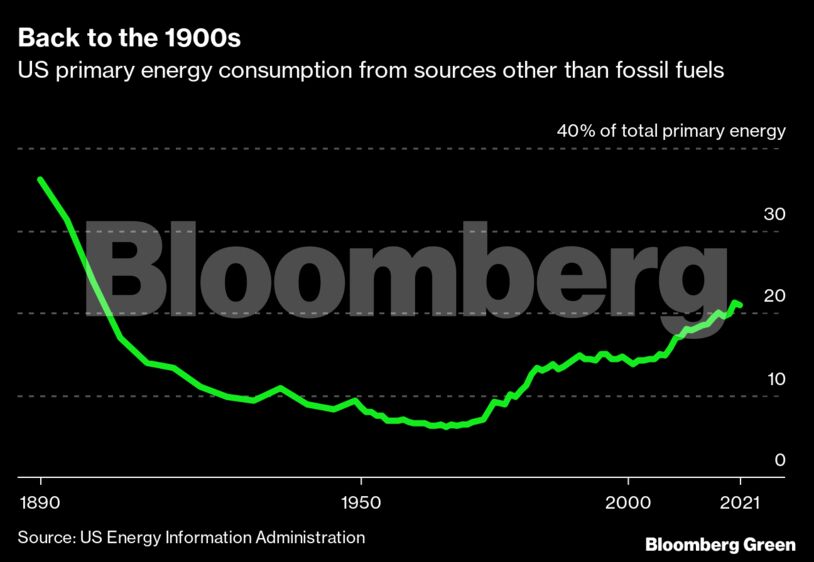

The combination of flat total primary energy consumption and rising non-fossil primary energy consumption means that the non-fossil share of US energy has been increasing steadily. Last year, zero-carbon and very low-carbon sources made up 20.8% of US primary energy. The last time their share was this high was the turn of the 20th century.

We can see, too, that since primary energy from fossil fuels peaked proportionally in the 1960s, there have been two major waves of decarbonization. The first was from nuclear power, from the 1960s through the 1990s; the second from renewables, starting in the 2000s.

Coal’s massive decline is due mostly to price competition from gas-fired power. Gas can eat further into the US power mix, but so too can renewables (or nuclear, should the US begin expanding its fleet again). Gas and renewables will be competing to dominate the American power sector in years ahead.

As renewable power continues to expand, it could (and should) be used to electrify processes. Some of those are small in scale but with a wide reach, like residential electric heating and cooking. Some are concentrated, like steelmaking. Others are nascent, but potentially huge, new sources of demand like producing hydrogen through electrolysis.

And if renewable power extends its reach into such processes, we could see the plateau in primary energy continue, or even see total consumption decline while supporting economic growth and innovation. That would be a very good thing: more final energy with less input, and with lower emissions as well.

Nat Bullard is a senior contributor to BloombergNEF and Bloomberg Green. He is a venture partner at Voyager, an early stage climate technology investor.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS