But the country may also be facing an uncomfortable reality as a result. As carefully cultivated relationships with firms such as BlackRock Inc. and SoftBank Group Corp. have yet to draw in the desired investment, it’s turning to the jewels of its energy industry to attract new money.

Last week’s sale of the stake to EIG Global Energy Partners LLC shows how reliant Saudi Arabia is on its traditional mainstay and the challenges Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman faces in diversifying the country away from oil and gas to achieve his Vision 2030 goal. The likes of BlackRock and SoftBank haven’t invested back into the country as much as the government might have hoped, while foreigners favor revenue-rich energy assets over tourism and entertainment.

“Entertainment and tourism might have had a better year of foreign direct investment in 2020 if Covid had not happened,” Karen Young, resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, said via e-mail. “But all the same, the core investors who see value in Saudi will be interested in the largest and most profitable sector, and that is still very much oil and energy.”

Though EIG, the Washington-based private equity firm led by Chief Executive Blair Thomas, is a prominent investor in North America and Europe, it barely resonates in Saudi circles. It hasn’t made a single equity purchase in the Middle East until now, let alone the kingdom itself, and its management team has never showed at Saudi Arabia’s marquee “Davos in the Desert” conference, an event attended routinely by investment leaders from The Blackstone Group Inc.’s Stephen Schwarzman to Ray Dalio of BridgeWater Associates LP and the Carlyle Group’s David Rubenstein.

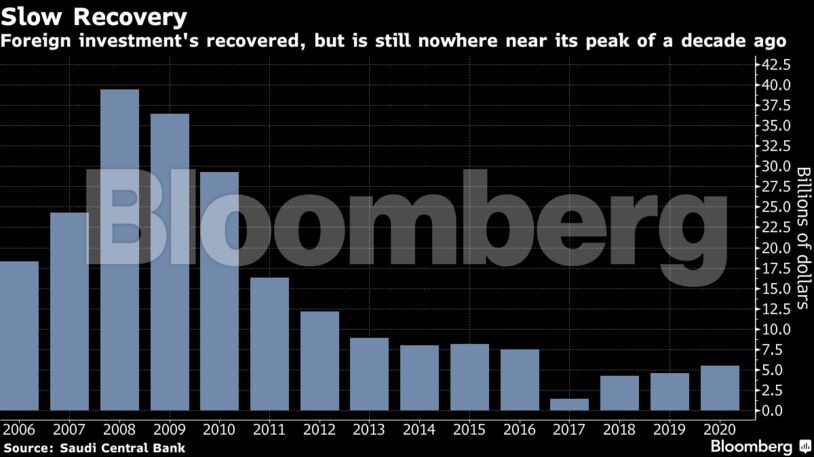

Saudi Arabia attracted $5.5 billion in net FDI flows in 2020, equivalent to about 1% of its economic output, according to data compiled by Bloomberg, which means the EIG deal brings more than twice last year’s total. The government’s goal is 5.7% by 2030, hence the temptation to offer up prized energy assets such as parts of Saudi Aramco, the state-owned energy giant.

“This is the latest milestone in an ongoing shift,” said Jim Krane, a fellow at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy in Houston. “Mohammed bin Salman and his advisers keep finding novel ways to coax cash out of Aramco without disrupting its operational capability. Right now it’s cash that the kingdom needs and Aramco controls the spigot.”

EIG beat out rivals including Apollo Global Management Inc. and Brookfield Asset Management Inc. to buy the stake. It’s now putting together a consortium of other investors to join the deal.

While several global investors have forged closer ties with Saudi Arabia in recent years, most of them see it more as a source of capital than an investment destination. The kingdom’s flagship Public Investment Fund, or PIF, is the largest investor in Softbank’s $100 billion technology vehicle, with an allocation of $45 billion. The PIF has also pledged as much as $20 billion to help Blackstone Group LP build the world’s largest infrastructure fund.

The reasons are manifold, ranging from the inconsistency of the Saudi legal system to an economic slump as the country adjusts to lower oil prices. The 2017 arrest and incarceration of scores of Saudi businessmen at Riyadh’s Ritz Carlton hotel and the murder of dissident writer Jamal Khashoggi the following year have hardly helped.

FDI into Saudi Arabia peaked between 2008 and 2012, averaging more than $26 billion. During those years, it was mostly driven by large refinery and petrochemical projects developed with foreign partners at a time when oil averaged over $90 a barrel. The subsequent slide in oil has seen average FDI into Saudi drop to about $6 billion a year.

“Despite the measures to liberalize and open the economy for investment into new industries, FDI has not come in the way originally planned,” said Monica Malik, chief economist at Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank.

FDI may be set to pick up further this year. The kingdom signed agreements with developers including Electricite de France SA and Marubeni Corpo. to build solar power plants last week, and later this year it is likely to complete the sale of the world’s largest desalination plant. In 2020, FDI rose 20%, in part driven by deals with Alphabet Inc. and Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. to develop cloud-computing hubs that Saudi Arabia said were worth a combined $1.5 billion.

In selling assets of its main state-owned energy explorer, Saudi Arabia is following a model successfully implemented by neighboring Abu Dhabi. Instead of pursuing an initial public offering of its state-owned energy firm Adnoc, the emirate has raised more than $20 billion in recent years by bringing international investors into some of its key assets. EIG studied some of the Adnoc assets that were on offer but couldn’t reach an agreement. Hence, it didn’t want to lose out on the Aramco transaction, a person familiar with the matter said.

Saudi Aramco is encouraged by the valuation and the interest generated for the pipelines deal, meaning the oil giant may pursue more disposals in the coming years, people familiar with the matter said. It has already entrusted boutique investment bank Moelis & Co with formulating a strategy for selling stakes in some subsidiaries, people familiar with the matter said in December.

“It’s a great deal for Aramco, but also a new kind of investment strategy, in that it is “giving up” much more in terms of investor access to information, control over operations than an IPO does,” said Young of the American Enterprise Institute. “It is a real partnership, a long-term effort with outsiders, which is an entirely new level of trust outside of the firm and the government.”

Founded in 1982, EIG has committed more than $34 billion to the energy sector, according to its website. Its portfolio includes holdings in Spanish solar developer Abengoa SA, Houston-based Cheniere Energy Inc., natural-gas producer Chesapeake Energy Corp. and storage and pipeline operator Kinder Morgan Inc.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS