Seeking to prolong the lifespan of an industry that’s vital to local economies, at least five states are seeking to pass legislation that would give them weapons such as bigger hurdles to shut coal-fired plants, a war chest for potential legal battles, more power to state regulators over utilities, tax cuts and cheaper state insurance for power stations.

The race to shield coal country from an energy transition that Biden contends will generate jobs and wealth in everything from solar-panel manufacturing to wind power generation highlights the political complexity of the shift to renewables. Even some Democrats in coal-producing states support the efforts to protect people’s livelihoods and the funding of schools and other public services in areas that derive income from the dirtiest fossil fuel. Meanwhile, utilities say the measures will drive up costs for ratepayers, while environmental groups say they’re only slowing, not stopping, the eventual move away from coal.

“It’s not planning for the future,” said Dennis Wamsted, an analyst for the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. “It’s protecting the past.”

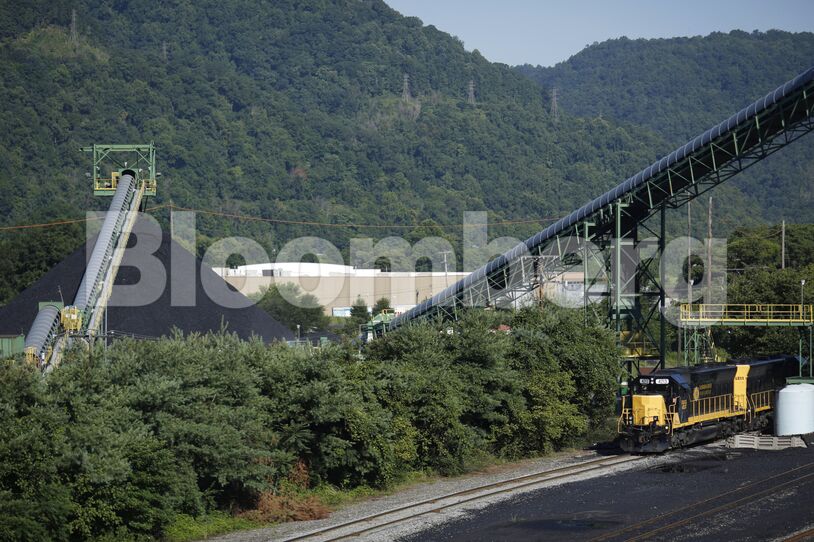

In Colstrip, a town in eastern Montana founded by the Northern Pacific Railway in 1924 to provide coal for steam locomotives, a power plant supplied by local mines has long been crucial to the area’s economy. That’s why Mark Sweeney, a Democratic state senator, supports proposals aimed specifically at keeping it open. Even though he recognizes climate change is a serious issue and that his stance makes him an outlier in his party, he says he worries about the devastating impact of a shutdown to the community. If it shuts, “it’s a ghost town,” he said.

Sweeney, who hopes the Colstrip plant can run for at least another 10 years, also argues that few emissions are produced delivering coal from the nearby mine, and that’s much more efficient than shipping the fuel to power plants in other states or across the world.

“The last one that should be shut down is the one that’s sitting on a coal pile,” he said by phone. “We have a whole lot of coal.”

In Wyoming, the country’s biggest coal producer, the Republican-dominated legislature is considering a bill that would require the Public Service Commission to assume that early retirement of coal-fired power plants isn’t in the state’s best interest, making it harder for utilities to shut facilities they’ve determined aren’t economic. Another proposal would set aside half a million dollars for legal challenges against other states that pass laws restricting the use of coal.

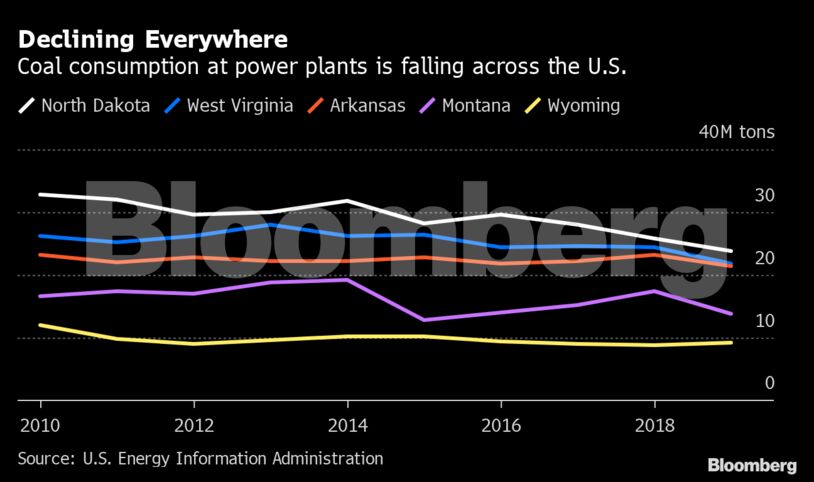

One of the goals is to protect mining jobs that underpin the local economy, said Eric Barlow, a Republican state representative who co-sponsored some of the legislation. His district in the northeast part of the state is in the heart of coal country, where output has plummeted in the past decade as utilities started using more renewables and natural gas.

“There’s no doubt we’re in a transition,” said Barlow, who raises cattle, sheep and yak on his ranch. “You can imagine what that does for jobs in this community.”

Republicans dominate the state’s government, controlling both chambers and holding the governor’s office. The effort is supported by the governor and at least some of the legislation is likely to become law, said Travis Deti, executive director of the Wyoming Mining Association.

“Wyoming is pulling out all the stops to try to save the coal industry,” Deti said.

The proposals don’t sit well with utilities, which typically seek to produce power at the lowest cost through a mix of generating assets. When a plant no longer fits into the equation — because maintenance costs go up at aging facilities, or another asset might have lower fuel costs or a coal site may need to install expensive pollution-control systems — then closing it will help ensure ratepayers don’t pay unnecessarily higher costs.

That’s what’s likely to happen if the state assumes more control over this decision, said David Eskelsen, a spokesman for Rocky Mountain Power, a PacifiCorp utility that operates four coal power plants in Wyoming. The company converted part of one of them to gas last year.

“Legislative attempts to force these plants to stay open does raise concerns about the price of electricity customers will have to pay,” he said.

Power providers in other states concur. West Virginia, the second-biggest coal producer, is considering a bill that would give state agencies additional oversight and approval authority over utilities that are seeking to close a power plant. The result could be higher power prices, or even making the state less attractive for outside investors, according to Jeri Matheney, a spokeswoman for Appalachian Power.

“It certainly would make closing a plant more difficult,” she said. The American Electric Power Co. utility has three coal plants in West Virginia, including the Mitchell facility that the company has said is close to being uneconomic and may go dark in 2028.

That’s what Rupie Phillips, the Republican state senator who co-sponsored the bill, wants to avoid. Coal accounts for about 20% of the state’s economy, and declining demand for the fuel at U.S. power plants threatens jobs in the region.

“I’m dead against shutting proven things down to make renewables more attractive,” he said. “Not on my watch.”

That strategy is ignoring a global trend away from fossil fuels, said Bill Corcoran, director of the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign.

“Sitting on a lot of coal reserves is no longer a path to prosperity,” he said. “These states are stumbling around to find some way to delay the inevitable transition.”

Other states are also pursuing legislation to protect local coal industries. North Dakota is considering a bill that would reduce taxes on coal power plants, while another would consider whether the state should offer insurance to the industry after premiums from third-party insurers climbed. Arkansas introduced legislation aimed at making it harder for utilities to close power plants.

In addition to the proposals to protect the Colstrip plant in Montana, another bill would require the state to evaluate the economic impact on local communities when a utility sought to shutter a power plant, another move designed to make the process of shutting down a site harder. While that one has been tabled in the Montana House of Representatives, its Republican sponsor Braxton Mitchell expects it to be picked up in the state senate soon.

“No plant, no mine,” Mitchell said. “No mine, no school, no libraries, no parks, no roads. It gets to be a pretty ugly picture pretty fast.”

(Michael Bloomberg, the founder and majority owner of Bloomberg LP, the parent company of Bloomberg News, has committed $500 million to launch Beyond Carbon, a campaign aimed at closing the remaining coal-powered plants in the U.S. by 2030.)

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS