By Meghan L. O’Sullivan

To push ahead, governments will need to go beyond simply devoting stimulus funds to cleaner energy, however welcome that is. Ultimately, policies will be more important than government spending in creating an environment in which all actors have sufficient incentive to advance the energy transition.

Such government activism seems more plausible than ever before. The Covid-19 crisis has generated conversations and actions that would have seemed fanciful just six months ago. The contraction of economies around the world and the swelling ranks of the unemployed have necessitated stimulus packages of unprecedented scale. Low interest rates have, for the moment, silenced most voices opposing new governmental debt, and a window for trillion-dollar spending initiatives has opened.

My Harvard colleague Larry Summers, the former secretary of the Treasury, recently said that we should worry less about saddling our children a huge national debt than about leaving them decrepit infrastructure, a substandard education system, and an antiquated system for collecting taxes and delivering social services. More Americans than ever seem to agree with that sentiment.

In many countries, the enormity of the crisis has thrust governments into the daily lives of citizens in a way that was neither seen nor welcome before Covid-19. While some governments have earned praise and others derision for their handling of the pandemic, few people have given up on the idea that governments — not civic groups, other institutions, or individuals — carry the primary responsibility for overcoming this challenge.

The longstanding American debate about the appropriate size of government will be shelved for some time, in favor of a conversation about the efficacy of government, regardless of its size.

Finally, the way in which the pandemic has exposed deep inequities in societies has opened the minds of many to addressing racism and systemic disadvantages of certain populations in a way that would have seemed highly controversial only last year.

These factors — along with a nagging sense that climate change could set off the next massive global crisis — are giving governments a chance to marry needed stimulus with ambitious plans to advance the transition to alternative energy sources, while at the same time addressing unemployment and injustice.

Most of the discussion of green stimulus projects remains aspirational. Columbia University’s Center for Global Energy Policy keeps a useful tracker of such projects, which suggests that 40% of stimulus has been green and 50% “dirty.” BloombergNEF, Bloomberg LP’s green-energy research service, is even less optimistic: A June estimate calculated that of the trillions in global stimulus measures passed, only $54 billion was devoted to clean energy while nearly $700 billion had been directed toward carbon-intensive sectors.

The notable exception is, not surprisingly, Europe. In July, a marathon meeting of leaders of the European Union resulted in an agreement in which climate is a central component. (Note: the BloombergNEF numbers were calculated before the conclusion of the EU summit.)

The EU package includes an $869 billion recovery plan, called Next Generation EU, alongside a $1.24 trillion European budget for the seven years beginning in 2021. The news headlines emphasized the significant amounts of money devoted to climate (roughly a third of the budget and the recovery plan), the emissions goals embraced, and the unprecedented move by the EU to issue joint debt.

But for those countries thinking about their own possible green stimulus, the relevant lessons may be more in the fine print. The real takeaway from the European package is that its authors appreciate that spending itself won’t be sufficient; it must be accompanied by government policies to shape the decisions and behaviors of nongovernment entities as well.

No feasible amount of government spending alone can generate the enormous investment needed in the energy sector to advance the green transition. The International Renewable Energy Agency estimates that $110 trillion of energy-related investment will be necessary for the world to meet the Paris climate agreement goals by 2050.

The European initiative puts climate at the center of the stimulus plan in ways not previously seen. Along with specific funding for climate-friendly initiatives, it appears to place constraints on nonclimate spending as well. The final document stipulates that “as a general principle, all EU expenditure should be consistent with Paris Agreement objectives.” Frans Timmermans, a vice president of the European Commission, earlier said not a single euro should be spent on propping up old, dirty industries.

How strictly this will be observed remains to be seen. While the deal does not preclude national governments from using their own money on fossil fuels, the breakdowns of spending offered by the EU appear to be in line with this “do no harm” principle.

Moreover, the European plan seeks to leverage the $12 billion Just Transition Fund (a component of Next Generation EU) to give EU member states incentive to adopt more ambitious climate targets. Countries that have not adopted the EU-wide target to become “climate neutral” by 2050 will only be able to access half of their allocation of the transition fund.

Importantly, the European plan addresses the question of revenue as well as spending. EU member-nations have agreed to a new tax on nonrecycled plastics starting next year, and have pledged to continue discussions on other revenue-raising mechanisms, including a controversial “carbon border tax” that would be introduced by January 2023. This is both a part of climate policy — nudging the market toward noncarbon sources — and also a fiscal necessity for Europe, given the need to identify how the joint debt will be paid back beyond member-state contributions to the budget.

Given low interest rates, the question of how these big climate initiatives will be paid for may not seem pressing. But over time, the sustainability of such broad-based measures — and the likelihood that popular concern over burgeoning debt levels will eventually create new political and financial constraints — will likely depend on how climate-action initiatives can pay for themselves.

Finally, the European Commission notes that it is committed to revamping the EU emissions trading scheme, a form of carbon pricing that now covers about 45% of the bloc’s emissions. Such measures are significant for their ability to help raise revenue to defray costs from other climate measures. But they are even more important as policy tools that shape the environment in which other actors make decisions. For instance, levies on carbon emissions were partially responsible for Britain’s recent dramatic move away from coal.

For a useful contrast to the European approach, consider the Chinese government’s stimulus efforts. Beijing’s plans reportedly provide more than $500 billion for special local government bonds to finance investments, some of which are green technologies. But Chinese plans also included hundreds of billions of dollars for carbon-intensive industries — and nearly 10 gigawatts of coal power projects have received permits since the onset of the pandemic. Clearly, the Chinese are placing economic growth and infrastructure over tackling climate change.

Then there is the U.S. It is unfair, perhaps, to compare the European initiative with the climate plan of Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden. One is an actual government document, while the other is a campaign proposal. But the Biden plan also seems to acknowledge — in different ways — that big climate spending (a proposed $2 trillion over four years) must be coupled with better policies.

At first read of the latest version of Biden’s proposal, one is struck by the strong emphasis on spending as a vehicle for creating union jobs. But on close inspection, the document also includes a variety of policy proposals in the forms of new energy standards and regulations aimed at shaping behavior outside the government realm.

That there is no embrace of a carbon tax in the Biden plan is striking, and indicative of how far to the left the climate movement has traveled. Just four years ago, a carbon tax was the centerpiece of Senator Bernie Sanders’ climate proposals. Today, it appears to have been largely abandoned in favor of a more complicated — and ultimately less efficient — set of mandates and subsidies in specific sectors.

This is unfortunate, as the leftward shift is occurring at the same time as a “moderate middle” could emerge around the need to put a price on carbon, which is the most market-friendly way of addressing the use of fossil fuels. Republican figures such as James Baker and George Shultz have endorsed the idea of a carbon tax, contingent on proceeds being returned to citizens via a dividend of sorts. Senator Richard Durbin, Democrat of Illinois, has introduced a climate bill that would establish a carbon fee, the proceeds of which would be split between a rebate to low-income families and funding programs to help communities dependent on the fossil fuel industry. One can hope that, if Biden is elected president, he will reconsider these ideas.

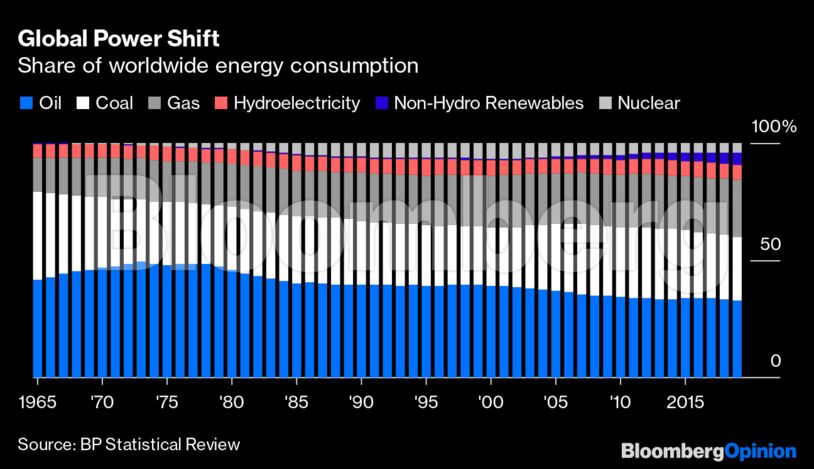

In the U.S. and around the globe, the Covid-19 crisis is speeding up many trends that were already underway; populism, nationalism and protectionism did not begin in the coronavirus era, but they have all been supercharged in it. Covid-19’s impact on the shift away from fossil fuels, however, is complex and unclear, as competing forces push the transition to occur faster or more slowly.

Governments have been granted enormous new powers by the pandemic, but they must remember that policy — even more than spending — will be what shapes the world’s transition toward a more sustainable energy future.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS