By Nathaniel Bullard

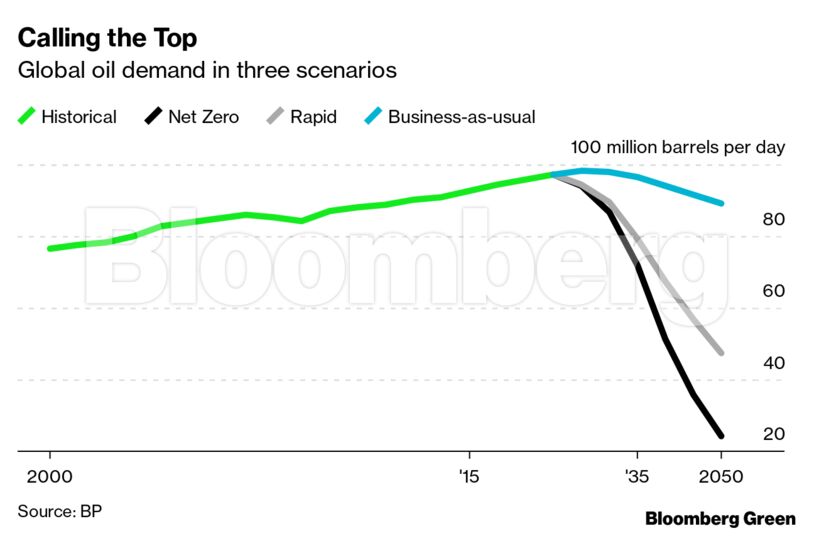

That’s the main takeaway from BP Plc’s annual energy outlook published this week outlining a handful of scenarios for the future of global fuel and electricity demand, and it’s a big admission in its own right. Even bigger is the way BP concludes it will happen: not because of aggressive policies aimed at reaching net-zero global greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, nor as a result of carbon prices or other interventions aimed at limiting global temperature rise to 2° Celsius over pre-industrial levels. No, BP says that even if energy policy keeps evolving at pretty much the pace it is today, oil demand will still start declining.

Even if governments take no drastic action on climate, BP sees oil consumption topping out not much higher than it is now: around 100 million barrels of oil per day, the same level as last year, though higher than June’s mid-pandemic 83 million barrels per day. In scenarios involving dramatic action by governments to limit climate change, the company determines that demand has already peaked.

It’s a big deal for an oil major to call the top on oil demand. Most industry planners have at least one long-term scenario in their portfolio showing that serious changes in demand and regulations could lead to declining consumption, but that’s usually framed as an edge case. OPEC’s demand scenario shows yearly growth shrinking to almost no growth at all without ever reversing. BP is the first big oil outfit to acknowledge that peak demand is far from far-fetched.

Under BP’s business-as-usual scenario, peak demand doesn’t mean a dramatic demand drop-off by 2050. The other two scenarios are far more drastic in this regard.

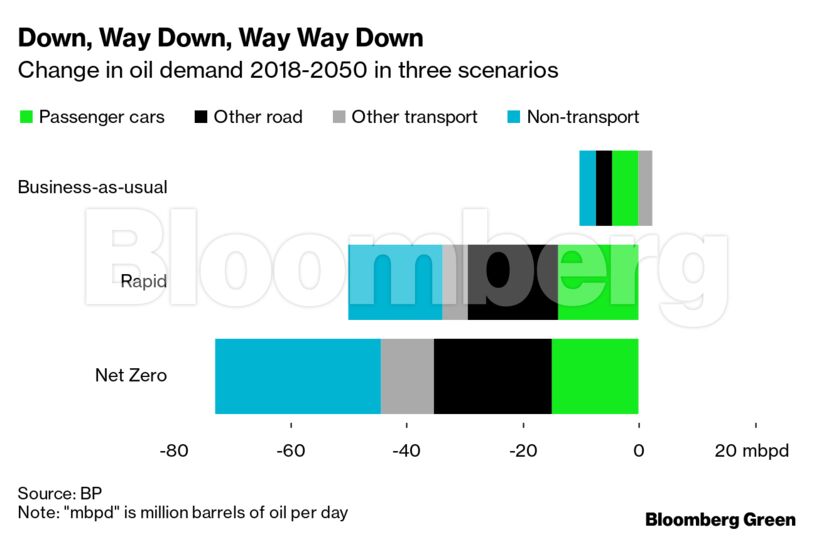

Not only does overall demand fall in every scenario, demand also falls in every energy-use sub-category save one: “other transport,” which is mostly marine and aviation. Even that will only be good for 2.2 million barrels per day of demand growth in the next three decades.

Scenarios are visions of the future, informed by data points, trends, and many variables. Other companies aren’t likely to change their stance on peak demand just because BP said its a thing. But there have been a handful other announcements in just the past week or so that all point in the direction of less oil consumption, not more.

Last week, Uber Technologies Inc announced its post-pandemic “green recovery” plan. Chief Executive Dara Khosrowshahi said that the company is committing to become “a fully zero-emission platform” by 2040, meaning that 100% of Uber rides will take place in zero-emission vehicles; in certain U.S., Canadian, and European cities, the company will aim to get there by 2030. In doing so, Uber is following the lead of Lyft, which announced a similar goal back in June. If other other fleets worldwide follow suit, could materially impact road transport-related oil demand.

In Europe, the bloc-wide emissions-cutting plan released Wednesday will “leave no sector of the economy untouched, forcing wholesale lifestyle changes and stricter standards for industries,” as Bloomberg News’s Ewa Krukowska wrote in her preview of the announcement. EU emissions are already declining in almost every sector except road and air transport—making those sectors prime targets for emissions-reducing policies and regulations.

And that “other transport” that was BP’s only net growth area for oil demand? Even there, we’re seeing plans to reduce emissions significantly via new fuels and technologies. In June, a consortium of some of the world’s biggest shippers launched the Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller Center for Zero Carbon Shipping. And last week, the 13 member airlines of the OneWorld Alliance also committed to reaching net zero carbon emissions by 2050.

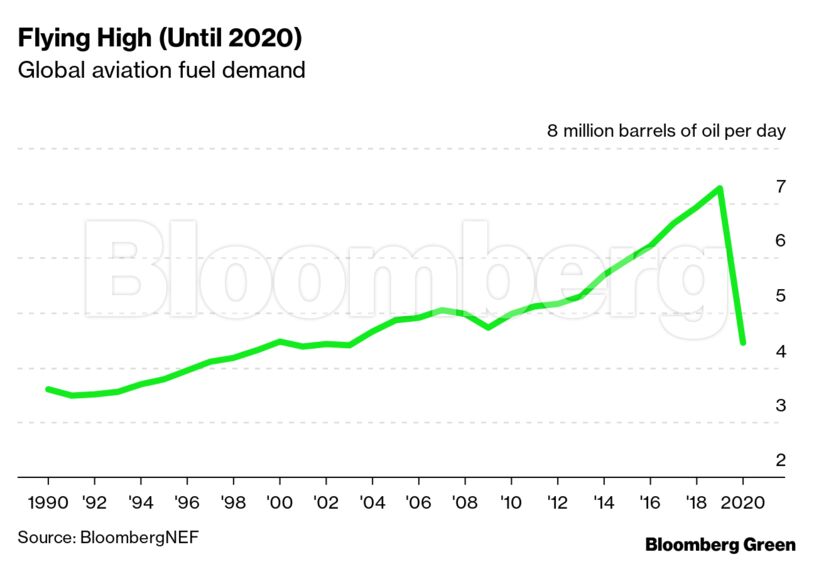

Aviation fuel demand has been climbing for three decades, though Covid-19 has put the kibosh on that trend for at least a few years.

The energy density of oil-based fuels used in aviation has meant that, to date at least, much of the effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from flying has taken place through the purchase of offsets. These, the logic goes, essentially cancel out the emissions from aeroturbine combustion by removing emissions elsewhere. Offsets will likely remain a substantial part of any effort to reduce aviation net emissions to zero, but there will also be plenty of innovation in creating new fuels, or even electrifying flight.

Spencer Dale, BP’s chief economist, introduced the company’s 2020 energy scenarios by musing on the nature of scenarios themselves. Scenarios “are not predictions of what is likely to happen or what BP would like to happen,” he said. Instead, “scenarios help to illustrate the range of outcomes possible over the next thirty years, although the uncertainty is substantial and the scenarios do not provide a comprehensive description of all possible outcomes.”

It’s a refreshingly candid view on the challenges of thinking long-term. It also highlights the significance of BP’s position on the future of oil. Peak oil demand isn’t an edge case, or laden with assumptions. It’s the new business as usual.

Nathaniel Bullard is a BloombergNEF analyst who writes the Sparklines newsletter about the global transition to renewable energy.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Fossil Fuels Show Staying Power as EU Clean Energy Output Dips – Maguire