By Liam Denning

For the most recent example of U.S. energy innovation, the shale boom, the conventional image of entrepreneurs spurred on by $100 oil is real enough, but incomplete. Both oil and gas continue to benefit from the large implicit subsidy inherent in letting greenhouse gas emissions go unchecked. That may sound like small government in action, but it is really just government inaction: a decision to abdicate responsibility and allow the privatization of profits alongside the silent socializing of pollution.

Energy has always been too important to abandon to the tender mercies of the market — just like public health. But as our current public health crisis demonstrates, importance doesn’t always correlate with the quality of policy.

For a useful recent example of what addled energy policy looks like, consider “energy dominance” — a buzzword that Trump elevated into “a strategic economic and foreign policy goal of the United States” in the spring of 2016. It refashions old fears of U.S. dependence on oil imports into an unstable blend of resource nationalism, protectionism and foreign-policy leverage. This concept’s incoherence reached an apotheosis of sorts last month, when Trump was reduced to haggling with the OPEC+ countries he had supposedly cowed while simultaneously gutting fuel-economy standards that would actually limit U.S. import dependence.

Children born during this spring of Covid-19 will likely live to see the year 2100. Our objective must be an energy system that is sustainable, competitive and resilient at least through their lifetime. That means supply and consumption patterns that power prosperity without storing up costs (or catastrophes) for future generations. One might say it’s the conservative thing to do.

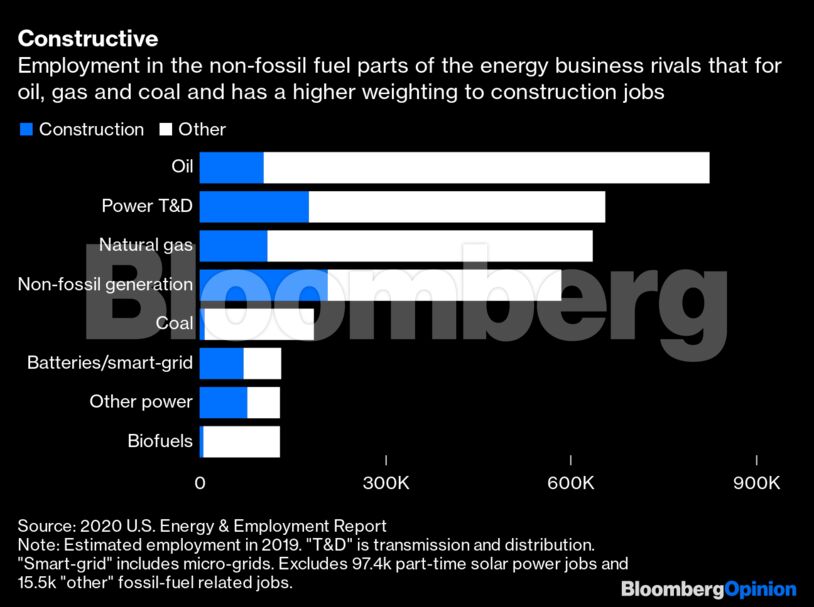

The aftermath of Covid-19 is a good place to start. The energy sector will play a vital part in meeting the economic imperative of getting locked-down Americans back to work. Roughly half of the 3.3 million Americans directly employed in energy are in the electric power sector outside of the bits that relate to fossil fuels. An expansion of electric power, with its inherent efficiency advantage over combustion technologies and its ability to use increasing quantities of renewable sources, is the sine qua non of a 21st-century system. Either we will invest to electrify more of our energy needs, particularly transportation, or we will pay the costs of climate change in lives, money and security.

Happily, electrification has always meant building lots of infrastructure. It’s tailor-made for a recovery plan prioritizing employment and investment in new technologies rather than just propping up old industries. Beyond this, an army of several million more Americans engaged in the fields of autos and energy efficiency are also primed to play their part; they’re agnostic as to whether the energy comes from the burning of a gallon of gas or the turning of a wind turbine.

The corollary of this initiative isn’t the collapse of the fossil-fuel industry. The ambulances wailing through New York City’s suddenly empty streets run on diesel or gasoline; so, too, do most of the cars and buses people will take when restrictions ease. Exactly how far demand for these fuels recovers is an open question, but it will certainly rise from today’s busted levels.

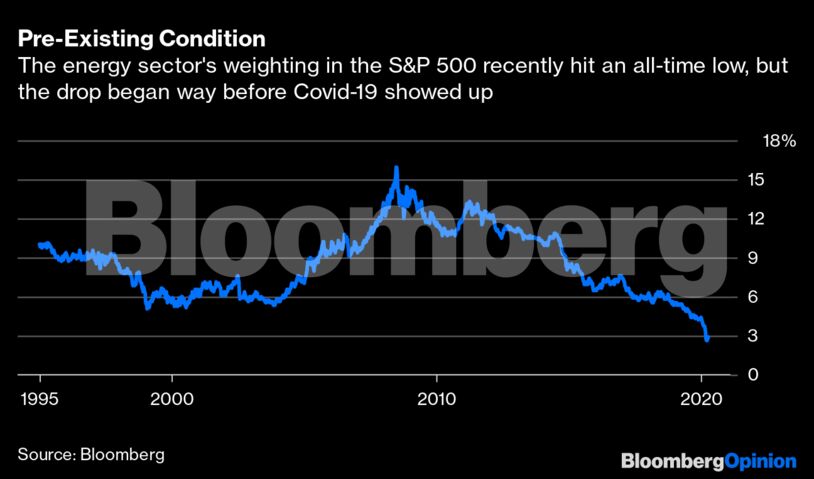

That doesn’t mean there should be a federal bailout, as Trump’s various calls or tweets for aid point toward. We already have abundant supplies of oil and gas, along with their carbon emissions, and the industry also happens to have just notched up a decade of awful returns. Throwing more capital at it makes little sense. Don’t take just my word for it, ask Mr. Market: Valuations for frackers collapsed well ahead of Covid-19’s arrival, as investors spotted the weak financial foundations of “energy dominance.”

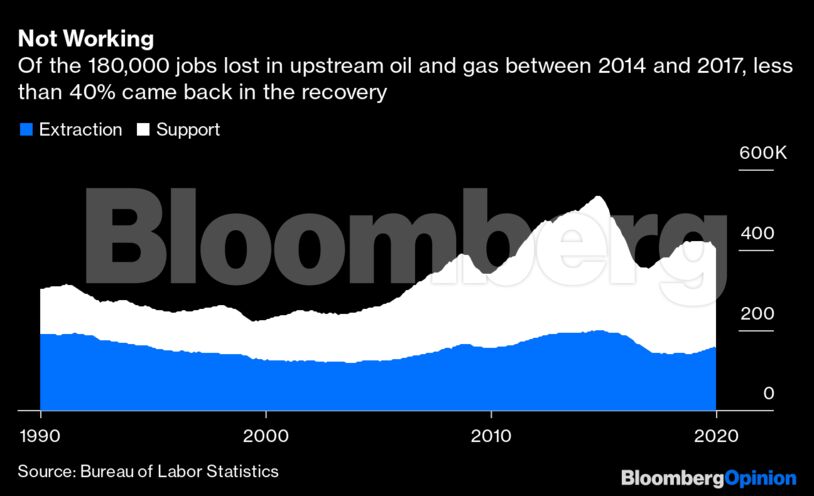

The arrival of the disease, alongside the OPEC+ price war, offered a glimpse of a future where oil producers fight for shares of a static or shrinking market. The best thing that could happen to the industry would be for it to rationalize and consolidate into a handful of companies better able to manage the risks of energy transition. As it does so, U.S. oil and gas will not be where many Americans get back to work. Just look at what happened after the last crash:

When it comes to oil, gas and coal, therefore, the immediate objective for energy policy should be alleviating the hardship on laid-off workers. Beyond Covid-19, the structural shift toward zero-carbon energy also represents a shock for workers caught on the wrong side of the transition. Markets move on quickly from old boomtowns; the people who live there often don’t have that luxury. Funding for retraining, relocation or direct financial aid must be part of the investment required for remaking American energy.

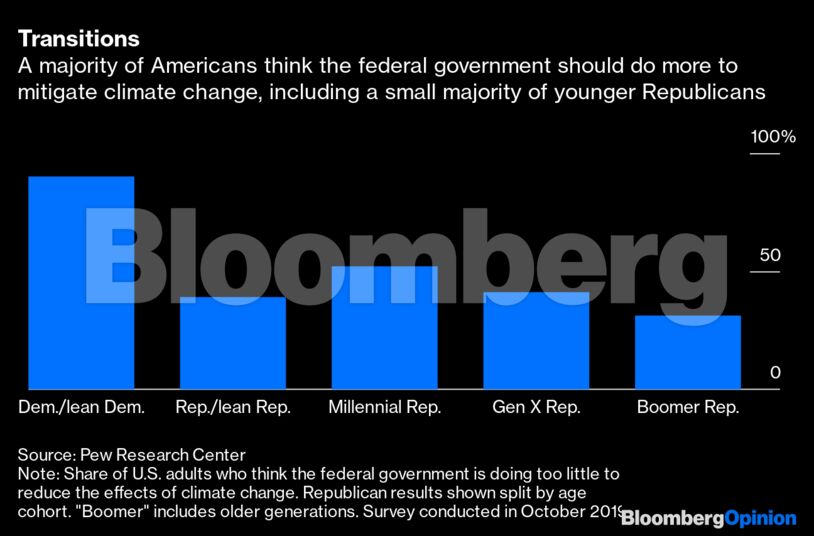

Talk of anything like an industrial policy for U.S. energy is apt to unnerve some folks. However, more than a decade after the financial crisis blew a hole in the orthodoxy of unfettered markets, we face another challenge demanding swift and coordinated government action. All the while, concerns about climate change have been creeping up, especially among younger Americans. There’s a growing cohort, in other words, who are more unnerved at the idea that government won’t do anything.

Remember, this sector is no stranger to government influence, overt and otherwise. The only issue is whether we would prefer that influence to be deployed sensibly and honestly or left as a mish-mash of conflicting interests, aims and methods. Consider the recent history of the Texas Railroad Commission, which spent years handing out permits allowing frackers to flare natural gas in the name of supporting the shale boom. Yet this effective subsidy encouraged ever more fracking, pushing down oil and gas prices and pushing up companies’ debts. Hence, we now find the commission’s biggest proponent of flaring permits calling on America to get into bed with OPEC on curbing supply in order to — wait for it — “protect free markets.”

Alongside a stimulus program aimed at refitting America’s energy system, we should harness the power of markets. That means real markets incorporating the full suite of costs and signals, not a cherry-picked version favoring vested interests. There is no such thing as “cheap” energy if all you’re doing is hiding the costs until they are someone else’s problem. The oil industry’s proponents of solutions such as carbon capture should not fear a price being put on that substance. If they mean what they say, they should advocate for it rather than simply gesturing at the governments they have spent decades (and billions) lobbying in the opposite direction.

Likewise, politicians dismissive of the Green New Deal, yet struggling to escape its gravitational pull on climate politics, should welcome clear price signals. The message from the deal’s champions is that the alternatives are outright regulation or bans. And there should be common ground here at least in terms of preserving America’s edge. “The last remaining bipartisan area of agreement in Washington is concern over U.S. competitiveness relative to other countries, particularly China,” says Sarah Ladislaw of the Center for Strategic & International Studies. A carbon tax would provide an important signal for innovators to shape and build on government-led infrastructure renewal, be it smarter grids or vehicle-charging networks. Proceeds could be paid back out to Americans to keep it broadly neutral (though how about reserving some for those communities currently tied to fossil-fuel production?).

Like the anti-lockdown crowd who were agitating for an Easter transmission party, some among us think that dealing with climate change is just too costly. It is, if we don’t get ahead of it; look at California’s recent experience with wildfires. But keep in mind an important distinction. Spending money ahead of time to mitigate a clear risk is an investment. Spending money after the fact to clean up the damage, or count bodies — that’s just a cost. Planning pays dividends. Leaving things to chance is what exacts a heavy price.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS