By Julian Lee

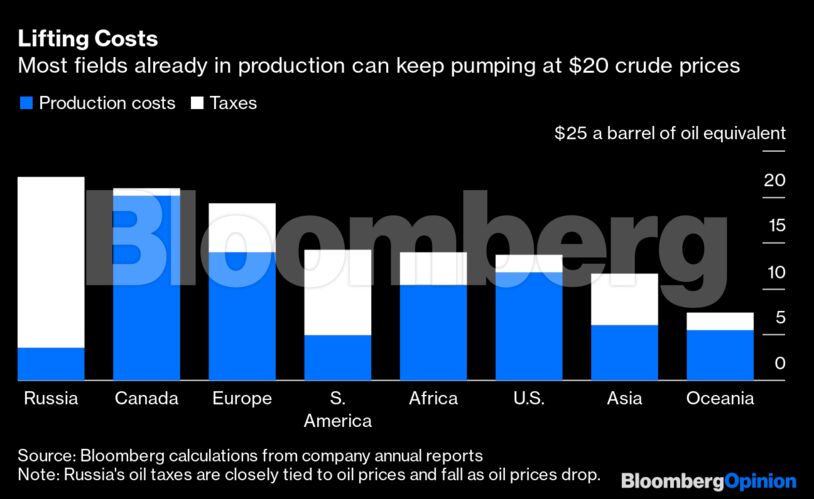

Oil at $30 a barrel, or even at $20, won’t stop most fields that are already in production from pumping, no matter where they are. Some will certainly be in peril, but they are not the huge high-cost deep-water projects beneath the waters of the Atlantic Ocean or in the Arctic. The most vulnerable will be the so-called “stripper wells” in the U.S. that pump less than 15 barrels of crude a day. They accounted for 10% of all U.S. production in 2015, but their importance has diminished as production from shale deposits has boomed.

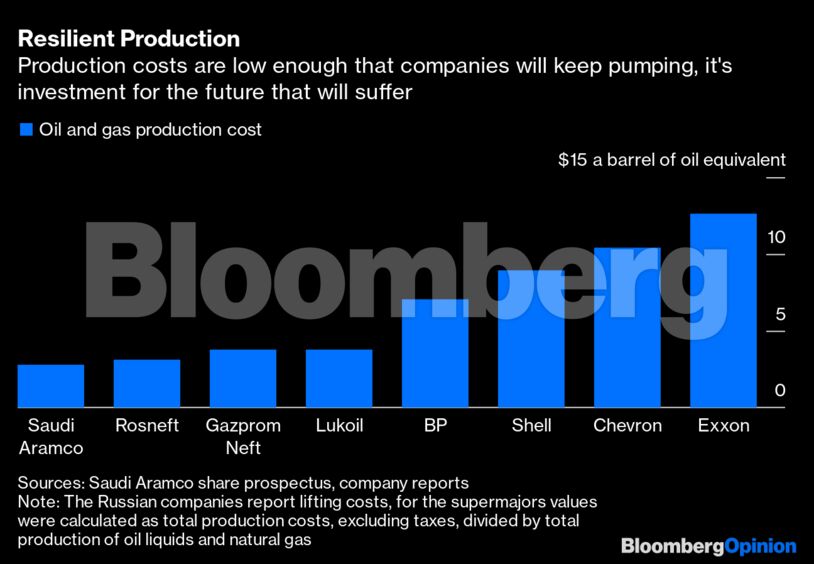

As long as prices remain above the cost of getting the next barrel out of the ground — the lifting cost — wells already in operation will keep pumping. And those costs can be pretty low. Saudi Aramco, the monopoly oil producer in Saudi Arabia, boasts an extraction cost of about $2.80 a barrel, according to the prospectus for last year’s initial public offering of its shares. Russia’s oil companies are not far behind, with Rosneft PJSC, Gazprom Neft and Lukoil PJSC all reporting production costs below $4 a barrel.

Even if prices do fall below lifting costs, the expense of shutting in a field may make it more economical to keep it running at a loss for a while in the hope that they pick up again, particularly as the cost of restarting production later may be prohibitively expensive.

This has certainly been the practice in the past. When oil prices fell to about $10 a barrel in 1999, amid the Asian financial crisis, operations halted at just one small Greek oil field — Prinos — that was pumping just 1,600 barrels a day. In the U.K. sector of the North Sea, the operator of a minor field also threatened to stop producing, until it got a discount on the fee charged to pump its oil to shore through a shared pipeline.

That’s not to say that some current output isn’t at risk if oil prices continue to fall. Projects in Canada face greater uncertainty than those elsewhere, with pre-tax operating costs of existing production around $20 a barrel. Outside of the U.S. stripper wells, this may be the first place to look for production being halted on economic grounds.

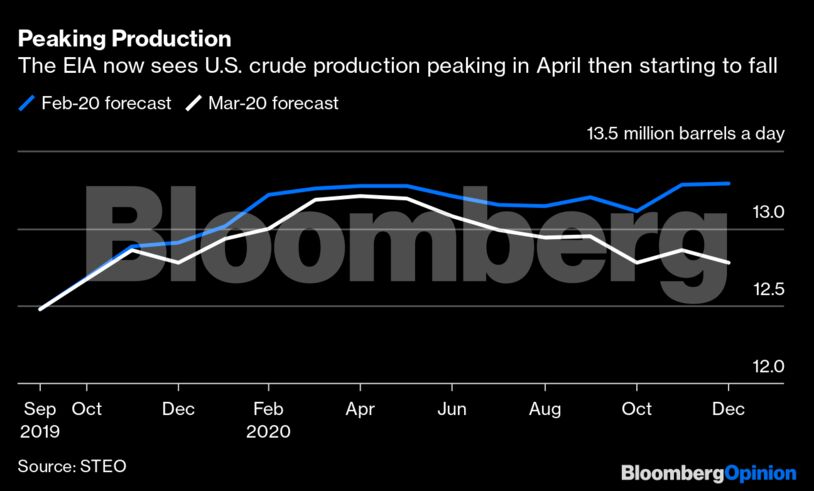

Shale production will also be hit, as a slowdown in drilling and completion combines with steep decline rates at new wells. The Energy Information Administration cut its forecast for U.S. crude production in its latest Short-Term Energy Outlook, published last week. It now sees output peaking at 13.2 million barrels a day in April and pegs December 2020 production back where it was at the end of last year, hastening the end of the second shale boom.

A geographical comparison from the annual reports of four major international oil companies shows that production costs in Russia were about $22 a barrel, including taxes, when oil prices were close to $70 a barrel. But Russia’s oil taxes are closely linked to prices.

What will suffer across the board, however, is spending on maintaining flow rates of current production and investment in new projects. The impact of the former could be felt by the summer, if maintenance programs at offshore fields are scaled back. Decline rates in countries such as Angola could become even steeper and will accelerate again if nearby fields are not drilled and tied back to existing production infrastructure.

But production costs mean little when it comes to deciding whether to invest in new capacity — even in Saudi Arabia. And it’s the aversion to new investments triggered by the price collapse that will have a much longer-term impact, potentially sending prices soaring again in the future. That will happen if capacity expansions in Saudi Arabia and other low-cost producing countries fail to keep pace with demand — demand that itself could get a boost from the same low prices — just as output declines elsewhere.

Even if the kingdom backs away from its pump-at-will policy, as it did previously with the introduction of the OPEC+ output deal in 2016, the threat of a repeat will continue to hang over the industry. In a world where oil prices are driven down to $30 a barrel or lower every few years, investing in new production capacity becomes a much more difficult decision to take. The Saudi safety net, which the global oil industry has come to take for granted, has just been ripped away.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS