By David Fickling

The argument that shareholder divestment campaigns don’t have a significant direct impact is probably right. Equity markets wouldn’t function without a diverse range of contrarian types with a high appetite for risk. To such investors, a major institution selling out of a cash-generative business like tobacco looks like an opportunity to buy at a discount.

It’s a different matter on the debt side, however. Indeed, there’s ample evidence that, contrary to Gates’s view, capital starvation is already rampant.

“Coal power plant financing is very challenging,” Dharma Djojonegoro, deputy chief executive officer of Indonesian generator PT Adaro Power, told Reuters in June. “In South Africa, out of the four biggest banks, three have stated that they won’t be funding us,” the former chief executive of generator Eskom Holdings SOC Ltd., Phakamani Hadebe, told a conference the previous month. The withdrawal of coal finance was raising the cost of funding, the chief executive of Polish generator Enea SA told shareholders in May. Adani Enterprises Ltd. has promised to self-fund a controversial Australian coal mine after local banks refused to stump up the cash.

Why should things be so different when it comes to debt?

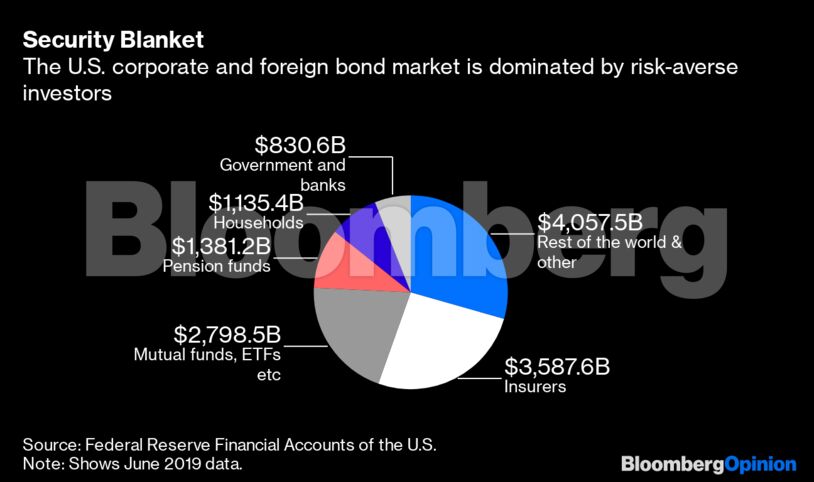

The equity market is kept alive by a large array of investors who like nothing better than to make a quick return by challenging the conventional wisdom, and don’t mind racking up a few losses as long as their better trades leave them ahead at the end of the quarter. Most debt investors are different — risk-averse, fearful of downsides, and more likely to follow the herd.

For the syndicated loans that most companies use to fund their day-to-day operations, it’s rare to have more than a dozen banks on the ticket. Bonds are a bit more diverse, especially at the high-yield end — but more cautious players such as insurers and pension funds still have the largest chunk of the U.S. corporate fixed-income market.

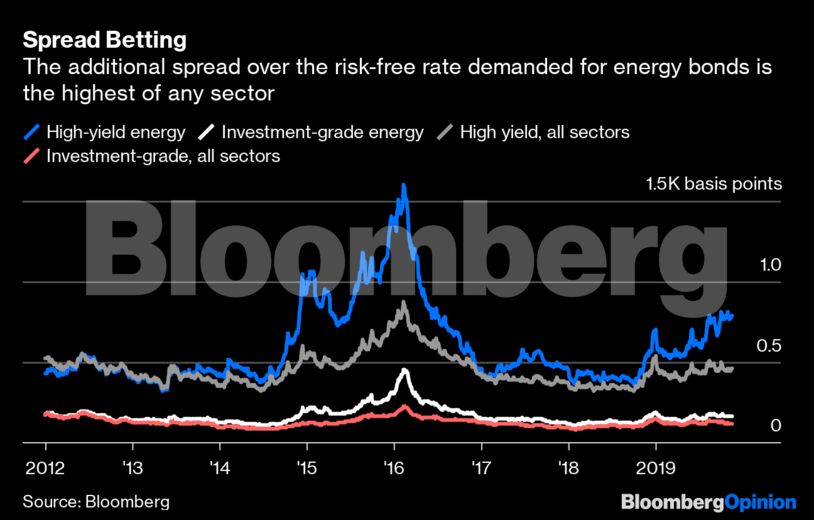

In this more circumspect corner of the capital markets, even investors who don’t have a problem with fossil-fuel finance may wind up backing out for fear of being left stranded by the retreat of other players, according to Fitch Ratings Inc.

“As the pool of investors willing to lend to coal projects diminishes,” the cost of debt issuance and refinancing rates could be affected “over concerns that other lenders will not be forthcoming,” the credit company’s macro research affiliate wrote in a May report.

Energy is already the highest-risk end of the bond market, with option-adjusted spreads — a measure of the extra return demanded by lenders over the government bond rate — well above other sectors.

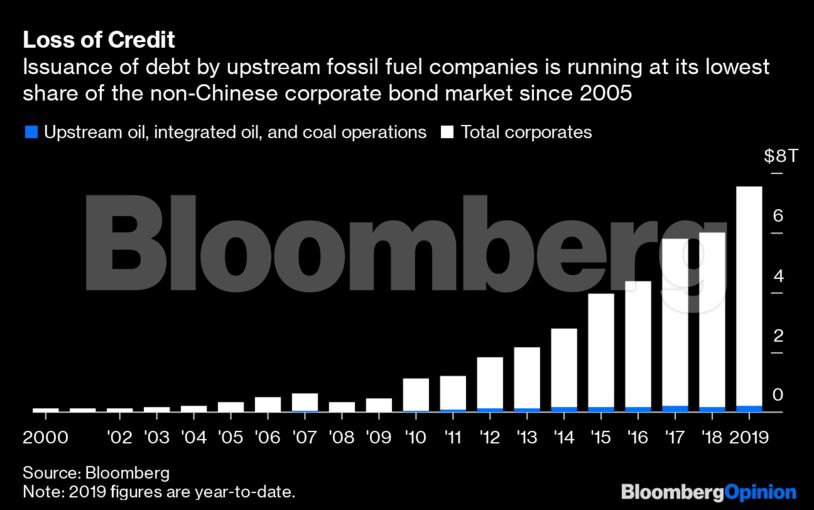

Even the debt binge that drove sovereign yields below zero across Europe this year has failed to set the market alight. Issuance of non-yuan debt by upstream and integrated oil and gas companies and coal producers is running 15% below its 2017 peak year-to-date, compared to a 32% increase in overall corporate bond issuance, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. As a share of total corporate issuance, the fossil-fuel extraction sector is running at its lowest levels since 2005, the data show.

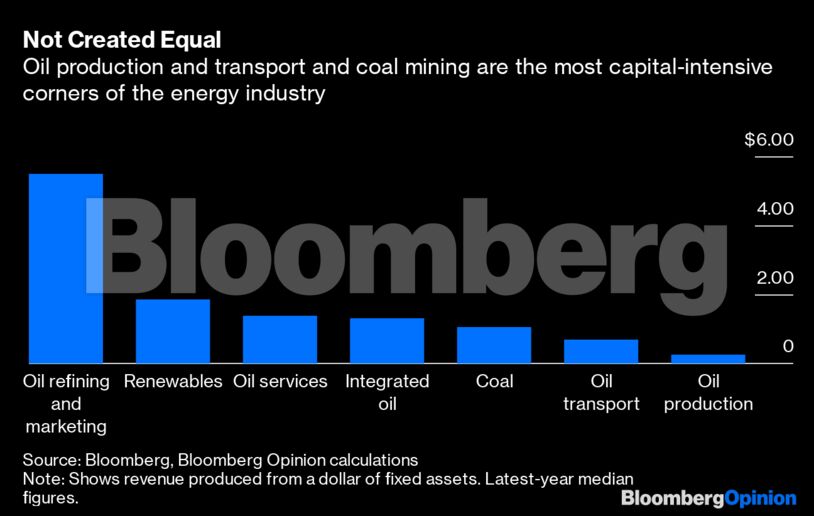

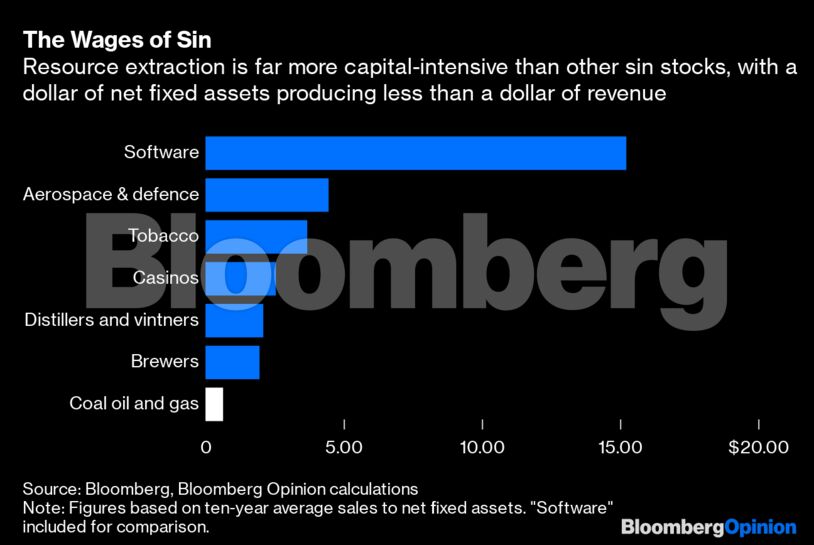

Gates’s history makes him peculiarly ill-suited to understand how damaging debt divestment can be. Microsoft Corp. funded its growth from earnings rather than loans, and has held net cash in every fiscal year since 1990, in part because software is about the most capital-light industry that’s ever been invented. Over the past decade, a dollar of fixed assets has been sufficient to produce $15.23 of revenue at the median software company, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

One common factor of most sin stocks is that they’re also relatively capital-light. Tobacco companies generate $3.68 of revenue for each dollar of fixed assets, and even aerospace and defense companies achieve $4.45, according to Bloomberg’s data. Resource extraction couldn’t be more different: Over the same period, a dollar has produced just 63 cents of revenue for coal, oil and gas. That makes these companies unusually vulnerable to changes in the appetites of lenders.

At present, more than 100 financial institutions have put restrictions on their funding for thermal coal, and 41 insurers have divested from or restricted their coverage of the sector.

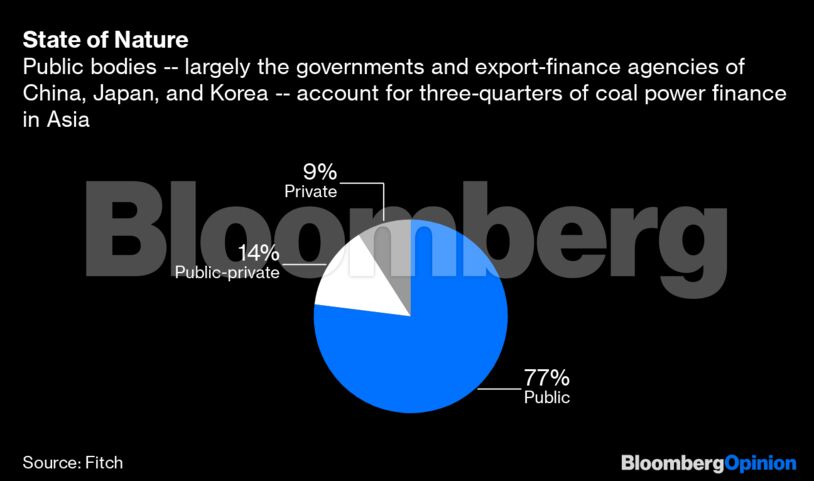

The little coal financing activity that’s still going on is largely dependent on government support from China, Japan and South Korea. State investors already account for 77% of coal power finance in Asia, and it’s increasingly likely that withdrawal of more investors could result in a “domino effect within the industry,” according to Fitch.

Don’t underestimate how quickly that could change things. Finance is the lifeblood of business. Cut off its flow, and the heart won’t keep beating for long.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Where the Fight Against Energy Subsidies Stands – Alex Epstein