By Gavin Maguire

LITTLETON, Colorado, Jan 30 (Reuters) – While North America and Europe scramble to build the data centers needed to run 21st-century businesses, many emerging markets remain anchored to 20th-century products like steel, cement and plastics for job creation and economic growth.

That divergence is splitting energy transition trajectories, too.

In the U.S. and Europe, the race to lead in artificial intelligence and data processing is overhauling power systems to deliver more electrons, more reliably.

Meanwhile, many economies in Asia, Africa and the Middle East remain tied to power-hungry heavy industry, mainly to churn out raw materials and consumer goods. That means fossil fuels – particularly coal – may retain a central role within energy systems for far longer than policymakers in the West assume.

CARBON-HEAVY

While the economies of Europe and the U.S. were initially powered by raw materials and heavy industry, decades of offshoring have resulted in the transfer of much of that smokestack production capacity to other regions.

Since the 1990s, China has been the primary location for the build-out of new capacity for the production of metals, cement, chemicals, ceramics and glass, and has in turn deployed those raw materials to develop its world-leading manufacturing sector.

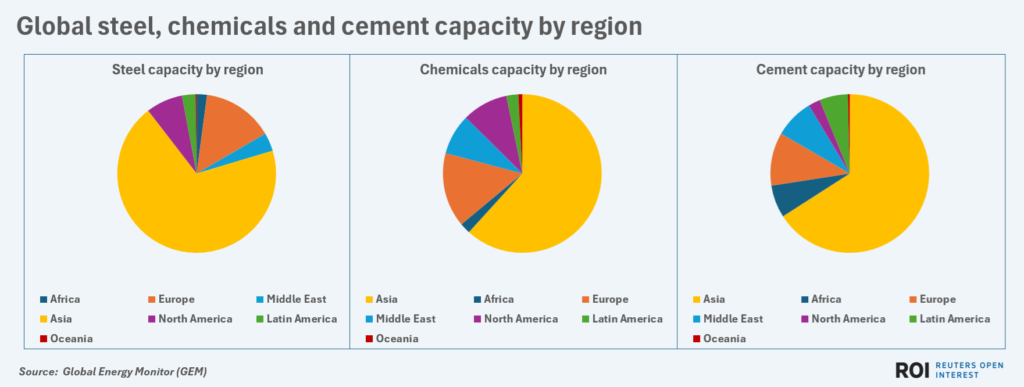

Global steel, chemicals and cement capacity by region

However, scores of other emerging markets including Vietnam, Indonesia, Nigeria, Egypt, Turkey and India have or are attempting to follow similar development blueprints, and are now also major producers of various raw materials.

Indeed, three-quarters of global production capacity of steel and chemicals is located in Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Latin America, data from Global Energy Monitor (GEM) shows.

When it comes to the capacity footprint for cement and clinker – the vital ingredients in concrete – around 85% of global capacity is outside of North America and Europe.

Economies across Asia, Africa and the Middle East are also leading the build-out of new steel, cement and chemicals, accounting for nearly 90% of capacity under construction.

CAPTIVE AUDIENCE

These countries are not just cheaper places to produce raw materials. They are also some of the fastest-growing consumers of cement, steel, plastics and related products.

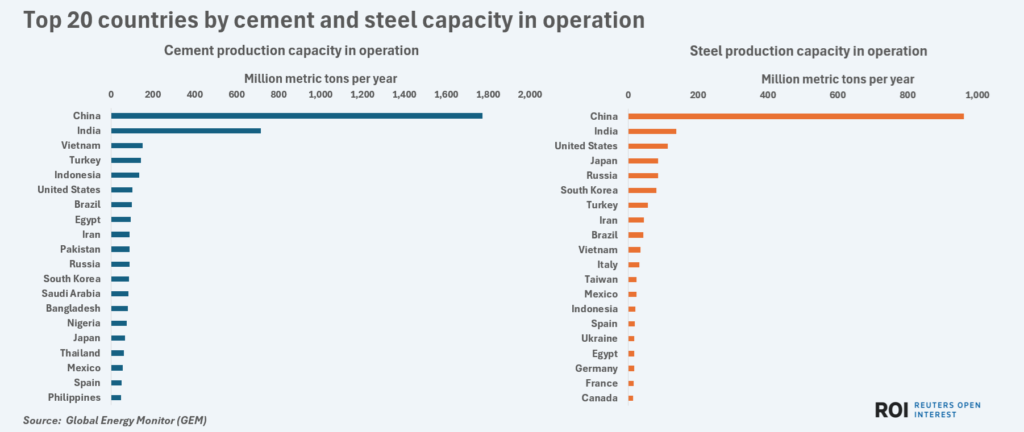

Top 20 countries by cement and steel capacity in operation

That combination of low operating costs and rising domestic consumption has helped reinforce the rationale for building up production capacity of those materials locally.

The build-out of the associated supply chains across trucking fleets, storage operators and processing facilities has created additional economic value and jobs, which further elevates their importance within local economies.

Throw in the potential for developing a manufacturing sector that can upscale those materials into pricier consumer goods and it is understandable why so many countries have policies that support basic materials industries.

ENERGY HOGS

However, such a deep dependence on raw materials for jobs and key intermediate products also shapes national power systems designed to keep these industries alive.

Making cement, steel and chemicals is notoriously energy-intensive, and producers need abundant, cheap power to stay competitive.

Many of these materials are also easily imported, which leaves local producers vulnerable to being undercut by foreign rivals.

That in turn pressures local authorities to ensure that operating costs remain as low as possible – especially energy costs – and to shape policy in producers’ favor.

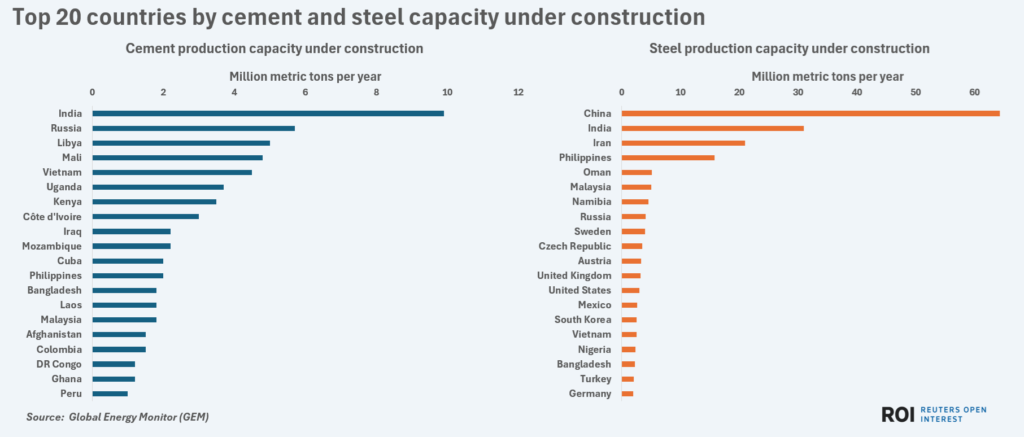

Top 20 countries by cement and steel capacity under construction

In fast-growing, cost-sensitive economies, the energy system becomes industrial policy.

Today, much of Southeast Asia as well as parts of North and Central Africa rely on coal for much of their industrial power supplies.

Extensive mining, import and storage facilities have often been developed to support and sustain that coal dependence, and coal-fired power is often among the quickest ways for those economies to ratchet up energy supplies.

Pushes to expand coal-fired power output may be at odds with the trends seen in more developed regions, and may reverse efforts to decarbonize energy systems.

But as long as basic materials like cement and steel pay most of the bills and employ large workforces, producer countries may not have the luxury to accelerate energy transition efforts without upending the broader economy.

The opinions expressed here are those of the author, a columnist for Reuters.

Reporting by Gavin Maguire; Editing by Marguerita Choy

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS