Suppliers with clients on tariffs linked to the country’s energy price cap are losing about 1,000 pounds ($1,349) a customer that can’t be passed on in bills. The whole industry is suffering and very few will have the cash to be able to sustain such losses for long, according to Keith Anderson, chief executive officer of Scottish Power Ltd., the U.K. unit of Iberdrola SA.

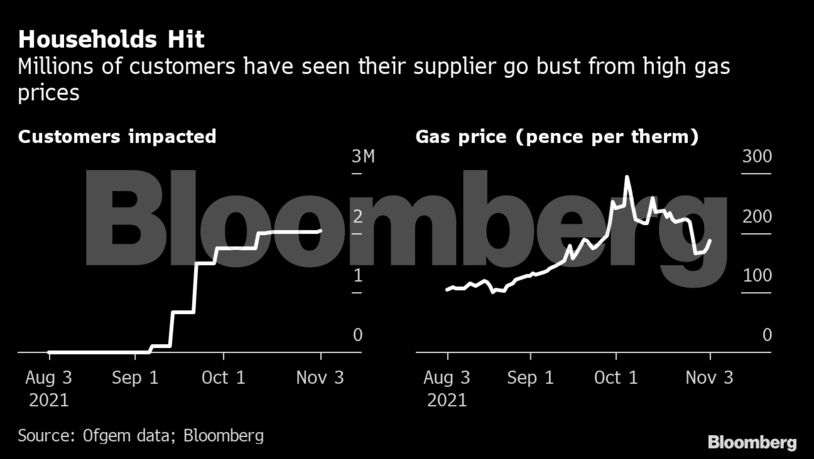

Some 18 companies have collapsed in the U.K. since early August and 25 domestic suppliers remain in a market that had almost twice that number at the start of the year. Several more look to be at immediate risk, with some companies missing a deadline to pay renewable levies and more unable to post credit cover required by market rules. Regulator Ofgem is planning to make changes to the price cap but these won’t kick in until April.

“For some of these companies, that’s too far away and between now and then they will have customers defaulting onto the price cap and it will drain their cash reserves so quickly and to such an extent that they will not be able to survive,” Anderson said in an interview in Glasgow.

“I think that there’s a significant risk that by April this market could be back down to five or six companies,” and those are likely to be the ones with international backers, he said. “Whilst this is hurting us, it’s costing us a lot of money, we are financially strong enough to be able to deal with that.”

A recent surge in power and gas prices, to levels three times higher than usual for this time of year, will be reflected in the price cap the next time it is adjusted. The issue is that today, the cost of supplying energy to the 12 million customers whose bills are capped is much higher than companies can charge.

The price cap could increase by almost 400 pounds in April, according to Cornwall Insight. That’s an increase that many of the poorest households will struggle to afford, according to Anderson. Consumers need to brace for a second big hike in bills in October when the costs associated with companies going bankrupt will be passed on.

Suppliers who step in to take the customers of failed companies have to purchase gas and power, though they can recover some costs later through levies on customer bills. That time-lag, plus the administrative burden, will make it difficult for the U.K.’s remaining energy retailers to absorb thousands or even millions of new accounts.

Changing how the price cap is calculated may partially solve the issues facing suppliers, but is likely to push bills up making life more difficult for the poorest households that the cap is supposed to protect, Anderson said.

Opening up the market was supposed to ensure consumers got a better deal from energy companies after a Competition and Markets Authority investigation found that customers overpaid by 1.4 billion pounds on their bills in the three years to 2015.

Attempts to increase competition by ending the dominance of the so-called Big Six companies resulted in the introduction of the price cap, and now that may be the cause of a return to the original situation.

“So you now have vulnerable and fuel-poor customers picking up the cost of regulatory failure and picking up the cost of company failure,” Anderson said. “I don’t think that’s morally right.”

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS