By Julian Lee

(Bloomberg)

A Saudi ruler replaces his oil minister for failing to deliver high enough prices as demand growth weakens and non-OPEC supply soars. I thought I’d woken up in 1986.

My former boss, Sheikh Zaki Yamani, was removed from his role as energy minister by King Fahd that year, after failing to deliver the impossible combination of higher oil prices — $18 a barrel was what the king wanted — and higher production for the kingdom. Outgoing minister Khalid Al-Falih seems to have faced a similar challenge. Except now the kingdom needs an oil price closer to $85 to balance its budget and, as ever, that seems to take priority over long-term considerations of market share.

Sure, there are differences, but in essence two competent technocrats lost their jobs for failing to deliver the impossible.

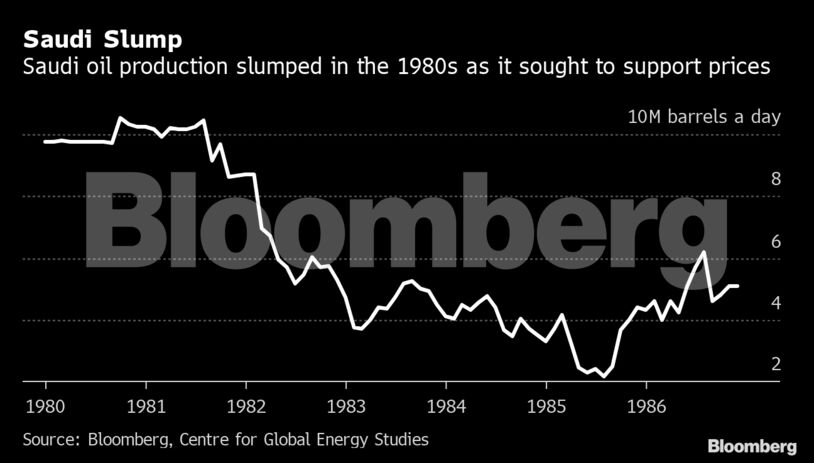

In the 1980s, Yamani saw Saudi Arabia’s oil production slump from more than 10 million barrels a day to little more than 2 million in less than four years, as the kingdom took the lead in trying to prop up oil prices while demand was weakening and non-OPEC output was jumping. The situation faced by Al-Falih wasn’t nearly so extreme, but his boss is a man in a hurry.

The current OPEC+ output cuts, of which Al-Falih was a key architect, were meant to last six months. They have now been extended to run into a fourth year and will almost certainly need to be be prolonged again, if not deepened. Saudi Arabia is bearing the brunt of those cuts and has said it will reduce exports even further this month. At the same time, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman, the de facto leader of the country, wants to float 5% of state oil company Saudi Aramco, at a price that would value it at $2 trillion. That might be challenging.

At least Yamani’s successor inherited an oil market that was turning in Saudi Arabia’s favor. Non-OPEC supply growth – driven then by the North Sea, North America and China – was faltering, while global oil demand growth was accelerating. Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman, who takes over from Al-Falih, is not in such an enviable position.

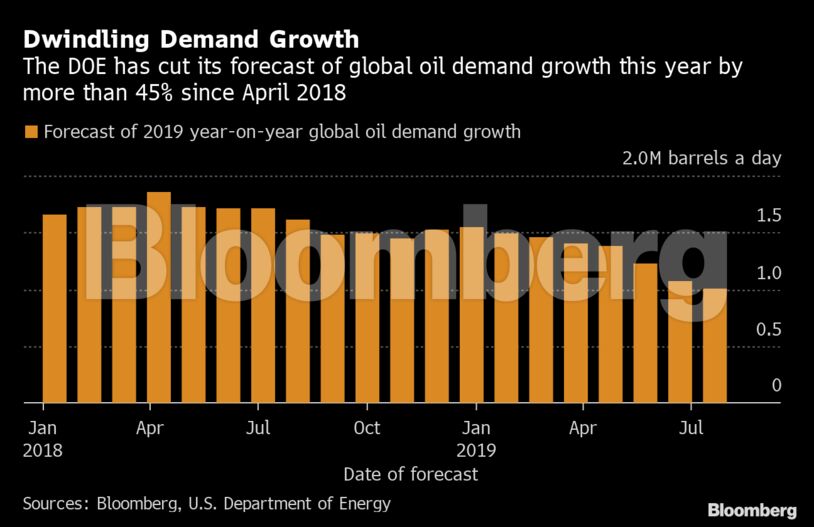

Oil demand growth is weakening, while U.S. production from the country’s vast shale deposits shows little sign of running out of steam. U.S. output hit a record 12.5 million barrels a day in weekly data last month, and new export pipelines and terminals expected in the coming months have the U.S. Department of Energy forecasting an output level of more than 13.5 million barrels a day by the end of next year.

That would be bad enough for any incoming Saudi oil minister, but this time it comes with an added wrinkle. Al-Falih’s successor is the first member of the royal family to be appointed to the job. Until now, the House of Saud has kept oil policy at arm’s length – at least superficially. Now it is bringing it in-house.

The previous arrangement allowed the royal family to portray itself as being above the sordid commerce of oil and to distance itself from responsibility when things weren’t going the kingdom’s way — for example, during the final years of Yamani’s tenure. Now, failure to turn around oil prices, or to secure that $2 trillion valuation for Aramco, risks showing the royals to be just as fallible as any other Saudi.

Note: Julian Lee is an oil strategist who writes for Bloomberg. He worked for Sheikh Zaki Yamani at the Centre for Global Energy Studies from 1989 to 2014. The observations he makes are his own and are not intended as investment advice.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS