By Kevin Crowley and Veena Ali-Khan

Exxon Mobil Corp. and Chevron Corp. are setting their sights on expanding production in nations tied to OPEC, including some of the world’s riskiest geopolitical hotspots, as President Donald Trump’s assertive foreign policy helps them strike deals.

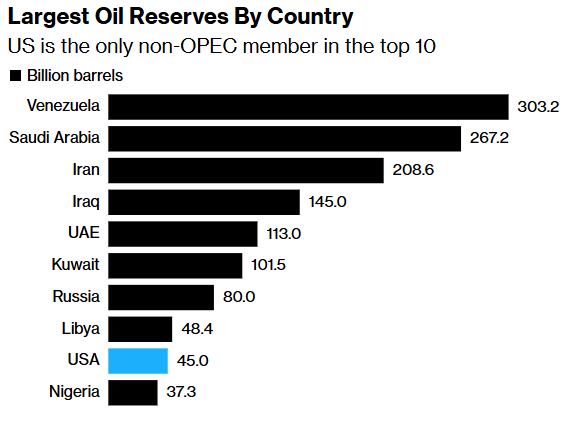

Venezuela, home to the world’s largest reserves, is the most high-profile opening of a nation that had been mostly off-limits to US investors after Trump captured former leader Nicolas Maduro and took control of the country’s crude exports.

But the US is also backing Exxon and Chevron as they negotiate in Iraq, Libya, Algeria, Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan, according to public announcements and people familiar with the talks who asked not to be identified discussing confidential meetings.

The US oil majors’ international forays are the latest example of how Trump has upended the norms of the ways American corporations do business, especially in industries he favors, like manufacturing, fossil fuels and cryptocurrency. While Europe’s oil majors — Shell Plc, TotalEnergies SE and BP Plc — are also seeking to expand in the Middle East, the US government support gives Exxon and Chevron a competitive edge.

“You have US ambassadors out there stumping on behalf of companies,” said Samantha Carl-Yoder, a former senior State Department official who helped US companies expand overseas under President Barack Obama and during Trump’s first term. “They’re running with it in a way that just didn’t exist under prior administrations, even Republican ones.”

While the major oil producers have operated within OPEC+ countries for decades, opportunities for new projects have been limited due to state control of their oil industries, tough contract terms and political instability. In recent years, the US majors preferred to grow their shale businesses in the US, helping America overtake Saudi Arabia as the world’s biggest producer in 2018.

But now, with host governments keen to win over Trump, gain implicit US security guarantees and avoid tariffs, US oil executives sense an opportunity for international growth that hasn’t existed since the mid-2000s. Investment in some of the world’s biggest oil fields would mark an expansion of Trump’s quest for American “energy dominance” and increase fossil fuel supplies well into the 2040s.

Source: OPEC

Note: Data excludes oil sands

Most of the world’s majors had the bulk of their biggest assets seized in the nationalization wave that swept the Middle East in the 1970s. Several attempts to return to the region failed due to tough contractual terms and political instability. Exxon has been nationalized twice in Venezuela in the last 50 years, and the entire industry was forced to leave Russia after the country’s war with Ukraine just four years ago.

The oil market can be unforgiving too. Exxon and Chevron spent heavily on overseas megaprojects that ran over budget and years behind schedule starting in the mid-2000s only to be hit with plunging oil prices in 2014 and again in 2020.

But with domestic shale production approaching a plateau and oil demand holding stronger than many forecasters had predicted, the US majors are on the lookout for what’s next.

Executives from both Exxon and Chevron have separately met with officials from Iraq, Libya and Algeria in recent months, often with senior members from the Trump administration. Special Envoy Steve Witkoff oversaw an agreement between Exxon and Azerbaijan in August.

“This energy dominance priority is certainly aligned with what we’re doing,” John Ardill, Exxon’s head of exploration, said in an interview. “But it doesn’t drive which countries we get into or how we enter them.”

Thomas Barrack, the US special envoy to Syria, helped facilitate a similar deal between Chevron and Damascus this week. Kuwait wants to attract foreign investment by opening up some of its oil fields.

“Pragmatic US energy policies and improved regulatory and fiscal terms in resource‑rich countries are creating an environment that supports responsible investment,” Clay Neff, president of Chevron Upstream, said in an emailed statement.

Read more: Oil Servicers Look to Middle East for Growth on Shale Slowdown

Though many of the Middle East accords are non-binding, all indications are that Exxon and Chevron are serious about pursuing concrete negotiations as they restock reserves for the next decade and beyond.

“We see the US majors gaining a disproportionate advantage given the US administration’s new, more aggressive approach,” Biraj Borkhataria, an analyst at RBC Capital Markets, wrote in a note. This “could lead to resource acquisition opportunities not available to European peers.”

The biggest prizes are the vast oil reserves within the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries and its allies in the OPEC+ group, despite the production controls the cartel requires.

Exxon operated one of Iraq’s biggest oil fields, West Qurna-1, after the US’s 2003 invasion, then exited in 2024 because it wasn’t making enough money despite the vast amount of crude there.

But now, surging supplies of oil from the Americas is forcing OPEC nations to re-think their approach to maintain their share of the global oil market. Several countries now say they’re willing to offer fresh terms in return for accessing the Western technology, know-how and capital needed to rebuild their aging oil fields.

Many governments want to imitate Guyana, where Exxon discovered oil in 2015 and now produces nearly 1 million barrels a day, Ardill said. The South American country, which recently became the world’s fastest-growing economy, agreed to commercial terms with Exxon that critics thought were too favorable to the company.

“It’s a realization in many governments that being creative and open to finding that right revenue sharing framework brings much greater value than just not ever getting there, and the investment not coming,” Ardill said.

Exxon signed an agreement to study Iraq’s giant Majnoon field in October. Chevron inked a similar agreement for the Nasiriyah project in southern Iraq a few months earlier. Both companies expressed interest in taking over the West Qurna 2 field, which produces about 10% of Iraq’s oil before current operator Lukoil PJSC agreed to sell most of its international assets to Carlyle Group.

Some within Iraq’s political elite see investment from the US oil majors as demonstrating the country’s independence from Iran, and believe it will help secure favor with Trump as relations between Washington and Tehran deteriorate.

Officials are said to have grown tired of the slow pace of development by Russian and Chinese companies and believe the presence of Exxon or Chevron could also help insulate the country from any future conflict involving Iran, Israel and the US, according to people familiar with their thinking who asked not to be identified discussing confidential information.

Little progress is likely to be made until Iraq forms its new government, which has been delayed since elections in November due to negotiations between factions under its power-sharing arrangements. Officials from the outgoing administration made no secret of their desire to partner with Exxon and Chevron.

Both US oil majors have also expressed interest in re-entering Libya after more than a decade of civil war. The country is offering exploration blocks holding an estimated 10 billion barrels of resources to foreign investors as part of a plan to increase production 40% by 2030.

The US oil majors are also seeing opportunities in Europe, Africa, Central Asia and the Caribbean.

Since Trump took office a year ago, Exxon has expanded in Angola, obtained offshore drilling rights in Greece, won exploration concessions in Egypt and signed a production sharing contract in Trinidad & Tobago, near Guyana.

Chevron is in serious negotiations with Kazakhstan about extending its license in the 1-million-barrel-a-day Tengiz field, signed a contract with Suriname and increased its exploration budget 50% this year. The oil giant has submitted bids for four offshore blocks in Greece and this week signed an accord with Turkey.

“Chevron is actively pursuing exploration opportunities to further strengthen and diversify our upstream portfolio,” Neff said.

Pursuing negotiations with multiple governments at the same time allows oil companies to pick and choose the best opportunities.

“We will very carefully select the best geology where we have the right commercial alignment with the government and where the geopolitical risk profile is acceptable,” Exxon’s Ardill said.

It also helps drive the best deals.

“More options equal more leverage,” said Carl-Yoder, the former senior State Department official. “It allows you to step back in fiscal negotiations and say, ‘Well maybe this isn’t working, we’re going to go someplace else.’”

— With assistance from Grant Smith, Khalid Al Ansary, and Anthony Di Paola

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS