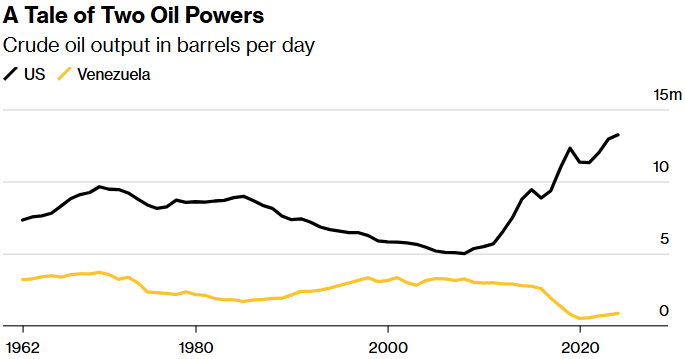

If it’s successful, and that’s a big if, Trump’s imperialistic investment would pay off shortly after US oil output peaks.

Rusty pipelines. Unchecked spills. Decades of chronic underinvestment, brain drain and mismanagement. Venezuela’s oil industry is in shambles, and restoring it to its former glory would cost an estimated $100 billion—if Big Oil would even want to undertake such a risky repair job. Also, the crude in its vast reserves is viscous and difficult to extract, and it would be slow to reach the market in significant volumes, in some cases taking as long as a decade. That’s too late to offer much in the way of lower prices during the remainder of President Donald Trump’s term.

So why is he pushing so hard to bring it back?

He wants any price relief he can get, sure, but anyone watching the supply and demand forecasts also knows it makes long-term strategic sense. The world is going to need a lot more oil in 2030 and 2040 than previously expected if current consumption patterns hold, and its biggest supplier—the US—is about to see its own output plateau.

Sources: Energy Information Administration, Venezuela’s PODE, Memoria Petrolera, OPEC secondary sources

No one agrees exactly when world oil production will peak, especially as offshore discoveries and the expanded use of fracking promise to prolong the fossil fuel’s lifespan. But the growth in shale oil production that propelled the US from being a net energy importer to the world’s No.1 supplier is nearing its end. Other fast-growing producers in the Americas—Canada, Brazil and Guyana—are expected to max out by the early 2030s, then go into decline. Globally, the industry needs to spend a startling $540 billion a year looking for oil and gas just to keep output at current levels by 2050, according to the International Energy Agency. If investments are limited to maintaining existing oil fields, production will fall nearly half by 2040, according to BloombergNEF.

At the same time, oil consumption continues to break records, even as the world grapples with the increasingly destructive effects of climate change. To avert the worst damage, experts agree society needs to wean itself off fossil fuels immediately. But while a decline in oil demand came tantalizingly into view during the pandemic, fossil-fuel consumption has since roared back, in part because of the slow deployment of renewables and the swelling power needs from artificial intelligence and the electrification of everything. Together, these dynamics threaten to push the oil market—today quite well supplied—into a shortage over the next decade.

“The US doesn’t need the oil at the moment,” says Marcelo De Assis, an independent oil consultant based in Rio de Janeiro. Trump’s push into Venezuela is more “like a hedge for the future.”

Before the US military’s capture of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro on Jan. 3, the world had mostly written off the founding OPEC member in terms of oil supply. Years of political turmoil, corruption and expropriations left it producing less than a third of peak levels, with little hope of a turnaround.

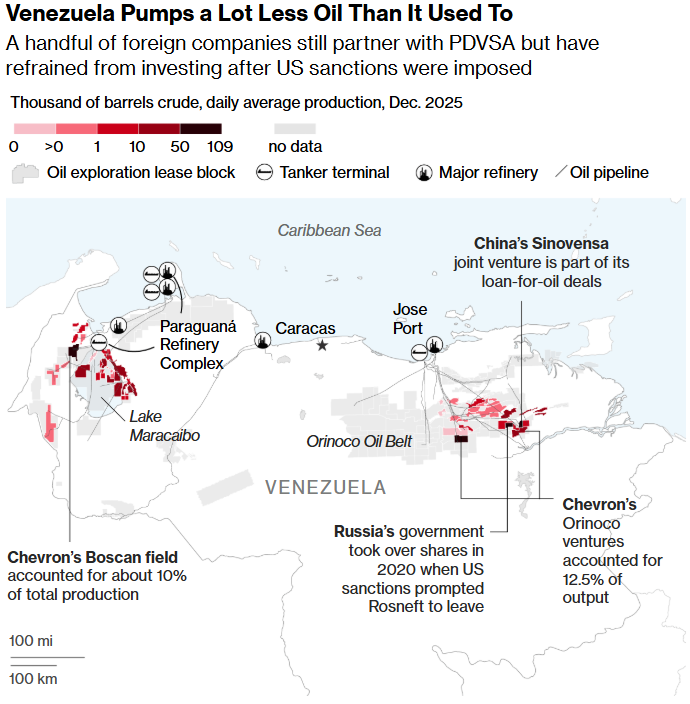

Source: PDVSA data

Note: Map includes the largest-producing oil blocks; some smaller blocks are not represented. Oil production data is the December daily average as of Dec. 11 (western fields) and Dec. 15 only (Orinoco).

Then Trump ordered the capture of Maduro and demanded “full access” to Venezuela’s oil reserves from the replacement leadership. He’s spoken boldly of the world’s biggest oil companies descending on the Caribbean country to fix its industry within 18 months. (Just seizing control and lifting sanctions on oil shipments would add some marginal barrels to today’s oversupplied crude market, potentially bringing prices down a hair from their roughly four-year low. That could notch a symbolic win for Trump, who repeatedly pledged to lower energy costs during his presidential campaign and is facing a cost-of-living crisis as he heads into the midterm elections later this year.)

The first wave of companies eager to tackle Venezuela’s run-down oil operations will resemble the less conventional risk-takers that are already there: small producers with low overhead that can profit from restarting minor fields. One of them is Maha Capital AB, a Swedish company with rights to a languishing oil project that could go from about 2,000 barrels a day to 40,000 by 2030, says Chairman Paulo Mendonça. While this would be a windfall for Maha’s shareholders, it will do little to make Venezuela a top oil producer again. All put together, these kinds of small investments will increase production by only about 300,000 barrels a day over the next two to three years, to 1.4 million barrels a day, according to consulting firm Rystad Energy AS. To return to 3 million barrels a day—roughly Kuwait’s output—it will cost $12 billion a year and take until 2040.

“We’re going to have a sustained, $100 a barrel price in the mid 2030s,” with the market “totally dominated by the Saudis,” says Schreiner Parker, head of emerging markets and national oil companies at Rystad. That is, “unless you have a Western Hemisphere counterbalance to that production—and that’s Venezuela.”

The level of ramp-up in oil output Trump envisions would require the majors to get involved in a big way. While the world’s largest oil companies are always eager to secure more reserves, especially with peak US production on the horizon, many have been burned before. In 1946, the year Trump was born, Chevron made one of Venezuela’s biggest oil discoveries, the Boscan field, joining Exxon and Shell as operators in what was then the world’s second-biggest producer, delivering 15% of global oil supply that year. Then, in 1976, Venezuela carried out a nationalization of its oil industry amid a wider move by oil-rich countries to take control of their natural resources. Chevron lost its prized Boscan field; Exxon and Shell lost even more.

In the 1990s, Venezuela invited oil companies back. Many returned, with Chevron going on to invest billions of dollars to develop the tar oil region in eastern Venezuela that makes the country the largest holder of oil reserves. Maduro’s predecessor, Hugo Chávez, launched another nationalization campaign in the mid-2000s, forcing big oil corporations to accept a lower share of profits or have their properties seized. “Massive oil infrastructure was taken like we were babies, and we didn’t do anything about it,” Trump told reporters following Maduro’s capture.

Chevron Corp. is the only big US company that decided to stay. Exxon Mobil Corp. and ConocoPhillips left; US oil companies still have outstanding arbitration awards worth billions. “For oil companies, the safest environment in which they could invest is when and if Venezuela has a democratic, stable, market-friendly and pro-Western government,” says Jimena Zuniga, an analyst at Bloomberg Economics. “There’s no better motivation for companies than when they have a high-reward and low-risk opportunity.”

Asked about plans for Venezuela, a spokesperson for ConocoPhillips says it’s “monitoring developments in Venezuela and their potential implications for global energy supply and stability” but that “it would be premature to speculate on any future business activities or investments.” Exxon declined to comment. Chevron declined to comment on whether it planned to boost its investments in the country, noting that it’s “focused on the safety and well-being of our employees, as well as the integrity of our assets.” According to US Energy Secretary Chris Wright, US oil companies are evaluating what role they might play in Venezuela. “They’re not going to sit on their hands,” Wright said on Fox Business Network.

Big producers have other reasons to tread cautiously. International oil giants have been consolidating and streamlining operations amid low oil prices, and it’s more expensive to produce crude under the existing terms in Venezuela than in Brazil or Guyana. Estimates vary, but Rystad’s chief economist, Claudio Galimberti, calculates the country has an average break-even price as high as $80 a barrel given the prolonged dearth of investment, costlier than many existing basins across the Americas. Venezuela’s oil is also higher in sulfur and denser—gloopier, even—than crude from other regions, requiring diluents and special equipment to process it, which means it tends to sell at a discount. US oil refineries on the Gulf Coast are especially good at refining this type of oil.

Given the hurdles, there’s a not insignificant chance this could all fall apart, and oil companies know that. “Trump would like to see the majors, but I don’t think they are in a rush,” says Carlos Bellorin, an executive vice president at Welligence Energy Analytics. “The fiscal incentives would have to be so good to compensate for the political risk.”

Still, the opportunity could prove enticing for oil majors looking at the longer term. After all, the US’s move away from electric vehicles and clean energy under Trump means it might be reliant on outside sources of oil in the coming decades amid the demise of shale. And for companies that have stepped up international exploration over the past year with a view to bulking up production after 2030, the opening of Venezuela could prove a game changer. Although pumping and burning that oil will have enormous consequences for the world’s climate, for energy companies seeking new supply but eager to keep their spending in check, “it’s a unique resource: organic reserves with no exploration risk,” says Rystad’s Parker. In the eyes of Big Oil, it might be “too big a resource to leave in the ground.” —With Kevin Crowley and Esteban Duarte

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS