By Jack Wittels

Weak oil prices are making it harder for the shipping industry to decarbonize, according to the president of commodities giant Cargill Inc.’s freight-trading business.

With a chartered fleet of more than 600 ships, Cargill has been at the forefront of the shipping industry’s efforts to cut carbon. Now, it’s hiring five new freighters that will be able to run on low-emission methanol as well as traditional oil-derived fuel.

The first, the Brave Pioneer, will soon arrive in Singapore, where it will take on green methanol — a type of fuel that’s estimated to cut carbon emissions by up to 70%, according to Cargill. Yet today’s economic realities mean the ship is likely to be running on oil in the not-too-distant future, Jan Dieleman, president of Cargill Ocean Transportation said in an interview.

“I can’t burn a fuel which is three, four times more expensive,” he said, adding that low prices for oil-derived fuel are among the headwinds for some investments in new technologies, elongating the payback time for energy-saving devices.

The Brave Pioneer is the world’s first Kamsarmax-class vessel that’s able to run on both methanol and oil; the four other ships Cargill is chartering are also dual-fuel methanol Kamsarmaxes. Delivered over the rest of this year and into 2027, they’re part of the firm’s broader forays into decarbonizing shipping that also include harnessing the wind.

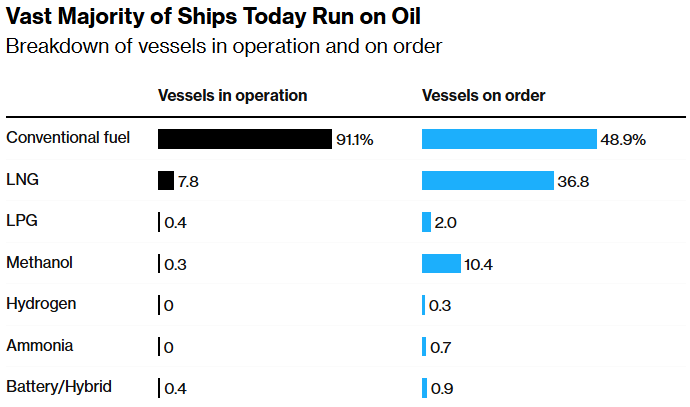

Source: DNV Maritime Forecast to 2050

Note: Conventional means oil-derived fuels such as VLSFO; LPG refers to liquefied petroleum gas; figures include LNG carriers, are as of August 2025 and are on a gross tonnage basis; a vessel being able to run on alternative fuel does not necessarily mean that it will

The Brave Pioneer encapsulates the difficulties of decarbonizing an industry which has greenhouse gas emissions that are bigger than Germany’s. Traditional fossil fuels are much cheaper than alternatives, a challenge that’s being exacerbated by slumping oil prices as the market contends with a surplus. A global carbon tax for ships would have helped bridge the price gap, but those plans are now on hold, adding to uncertainty for transition-focused investments.

The difference in fuel prices is sizable on a dollar-per-ton basis: last month, 100% sustainable methanol in Singapore cost more than $1,000 a ton, whereas oil-derived marine fuel was well below $450 a ton, according to figures from S&P Global Energy. The true gap, however, is even bigger: methanol is less energy dense than oil, so shippers require more to travel the same distance.

Cargill isn’t alone in exploring methanol as a marine fuel: there are at least 450 methanol-capable ships in operation and on order, according to ship classification society DNV. The green, bio-methanol that will be bunkered in Singapore is being supplied through Seascale Energy, a joint venture between Cargill and tanker owner Hafnia Ltd.

While acknowledging the cost gap between oil and cleaner ship fuel, as well as the uncertainty around future regulations, Dieleman said he’s still upbeat about decarbonizing shipping. Fuel prices are volatile, and there are myriad possibilities when it comes to environmental policy, he said.

“I’m still very much a believer that this industry will transition to lower carbon — and eventually zero carbon — fuels,” Dieleman said. “But when you’re running a business, you also need to think about the timing.”

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS