Donald Trump’s hatred of wind power continues. In a speech in Davos last week that managed to upset almost everyone, the US president still found time to get in a few trademark digs at renewable energy. “There are windmills all over Europe… and they are losers,” he said, in a strange anthropomorphism. “One thing I’ve noticed is that the more windmills a country has, the more money that country loses, and the worse that country is doing. I haven’t been able to find any wind farms in China.”

The first points to make are that windmills make flour, not electricity, and China has more installed wind power than any other nation. The other point is that Trump’s wind skepticism seems to be contagious. Once upon a time, securing more wind power would have been celebrated by everyone, no matter their political colors. But a recent round of renewable energy subsidies in the UK highlights just how much sentiment has changed, and how climate action is facing an enormous communications challenge at a critical moment.

One way the UK supports renewable-energy development is through auctions for so-called contracts for difference (CfDs). Wind-farm developers compete for the agreements, which guarantee them a certain price per megawatt hour, by bidding their minimum viable price. If the company can sell wholesale electricity for more than the contract price, it pays the government the difference, and vice versa if energy is cheaper. As well as making renewable-energy projects less risky, CfDs protect electricity consumers from price spikes.

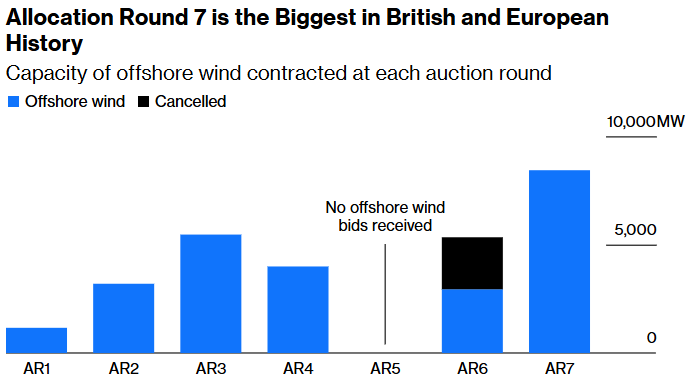

This month the UK government announced that companies had been awarded subsidy agreements to supply a record 8.4 gigawatts of offshore wind power, including 192 megawatts of innovative floating turbines — which are tethered to the sea bed rather than fixed to the floor — after a hugely competitive auction.

The ruling Labour Party’s goal of getting at least 43GW of offshore wind online by the end of the decade is now within reach, which would probably make up about a third of the UK’s installed capacity for power generation. Although nothing is guaranteed, there’s hope the next auction will be just as popular.

Source: DESNZ

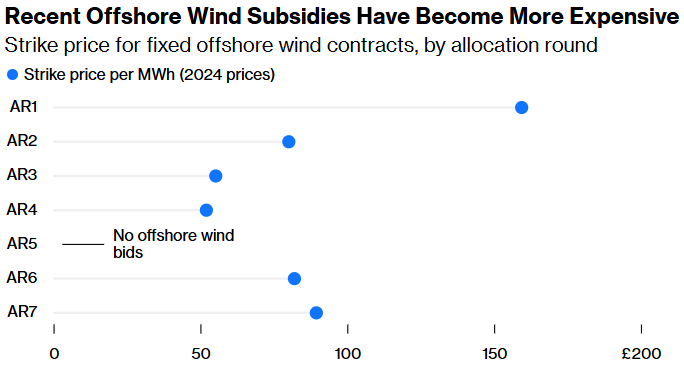

But critics are questioning whether the price set by the January auction is good value for money. It guarantees developers between £89 and £91 (about $120) per megawatt hour for fixed-bottom offshore wind, depending on the location, for 20 years. That’s a rise of 11% since the last round in 2024, and with the current wholesale electricity price hovering around £80, this batch of wind-capacity looks to have come at a premium.

Source: DESNZ

Note: Where there is a range of prices in one allocation round, the lowest value is used.

Yet the price hike doesn’t mean this is a bad deal for British energy consumers. A problem with wind power is that some of the country’s turbines are located far away from areas of high electricity demand. With not enough transmission lines to carry excess power where it’s needed, wind farms often have to stop producing (while still being paid) because the energy can’t be delivered to the right place. The good news is that the locations of new projects in this auction have been carefully chosen. Some 83% of the fresh power connects to the grid in areas of strong demand and greater network capacity.

Critics also claim that the new wind pricing will push up electricity bills by increasing levies and capacity costs. But, somewhat counterintuitively, two separate analyses, one from management consultancy firm Baringa and another from Aurora Energy Research, found that, so long as the price was less than £94/MWh, new capacity would come at no additional cost to billpayers. We’re a few pounds under that threshold.

Though the price guarantees for the new CfDs will make up an increasing share of bills in future, that should be more than offset by reducing our reliance on imported gas — and its volatile pricing — and lessening the expensive need to shut down wind-power supply (and boot up gas power) by building turbines where demand is strongest. Even without this, wind’s benefits are clear. The Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit think tank found wholesale power prices would be almost a third higher in 2025 without the help of windfarms.

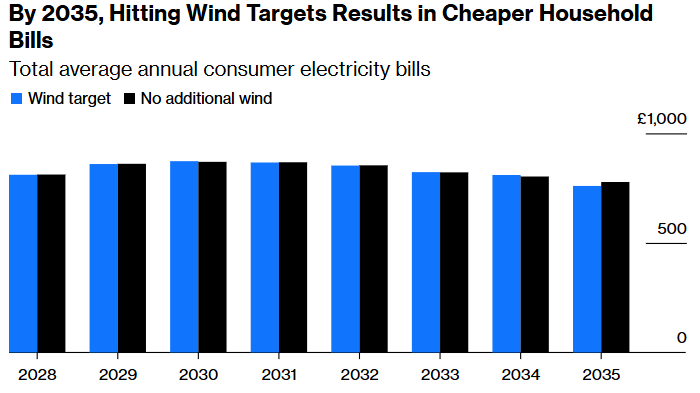

Electricity bills are expected to rise until 2030, regardless of how much is spent on renewables, largely because of desperately needed investment in the country’s gas and electricity networks. But after the turn of the decade, costs will start to fall. Compared to a world in which no additional wind is secured, hitting Labour’s target will make our bills £17 cheaper per year by 2035, according to Aurora’s analysis, which accounts for the costs of dealing with wind’s intermittency.

Source: Aurora Energy Research

Note: Based on a wind strike price of £94/MWh.

It’s not an easy concept to explain to the public or an incurious US president. To understand why renewables will make bills cheaper, they have to imagine a fossil fuel-powered counterfactual. Oil and gas, remember, aren’t free. And the damage done by pollution isn’t priced in. The government’s figures put the cost of building and operating a new-build gas plant at £147/MWh, based on it running 30% of the year, which is in line with our current fleet. That’s much more expensive than the equivalent calculations for renewables. Even if carbon costs are ignored, gas only comes down to about £105/MWh.

Ignoring all this is a mainstay of climate-change denial. The Institute of Economic Affairs — a think tank that helped inspire former Prime Minister Liz Truss’ infamous mini-budget — recently produced a pamphlet wrongfully claiming that “net zero” would cost £4.5 trillion (£7.6 trillion if you include operating costs.) They reached that figure via either a total misunderstanding or willful manipulation (take your pick) of analysis done by the National Energy Systems Operator, adding up all the costs for its climate-friendly “Holistic Transition” pathway and imagining that a fossil-fuel pathway would be free.

As Mike Thompson, NESO’s chief economist, put it: “We’d still spend most of this without net zero… Unless you think we’ll stop driving cars, stop heating homes and stop using energy — for anything!” In reality, over the entirety of the next quarter of a century, NESO’s net-zero pathway ends up being £360 billion more expensive than the IEA’s preferred route, which cuts emissions more slowly and doesn’t actually reach net zero.

Despite the misinformation, the IEA’s numbers ran largely unchallenged in several British newspapers. It’s important that proponents of climate-protecting policies are willing and able to defend their own calculations, yet that must apply to the antis, too. Hitting net zero is the problem of our age and is a complex subject that needs careful unpicking for the public. Sadly, too many people prefer to obfuscate.

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS