New Fortress Energy went all in on a concept it called Fast LNG. Slowly that commitment has become the company’s undoing.

By Ruth Liao, Liam Vaughan, and Jim Wyss

For 20 minutes, Wes Edens barely pauses as he talks about the sunny prospects for his beleaguered liquefied natural gas company, New Fortress Energy. Dressed in an open-collar blue shirt, his once-blond hair down to his neck, the effervescent 64-year-old billionaire from Montana appears relaxed, flicking through a printout of a PowerPoint presentation he says he prepared himself. It outlines NFE’s operations in Brazil, Mexico and Nicaragua, as well as the global growth potential of liquefied natural gas, or LNG.

It’s a cloudless November morning in Puerto Rico, where NFE supplies more than a third of the island’s natural gas and operates a handful of power plants. Edens, who made his fortune in private equity and co-owns both the Premier League team Aston Villa and the NBA’s Milwaukee Bucks, has invited Bloomberg Businessweek to his company’s facility at the Port of San Juan to explain why, in spite of evidence to the contrary, NFE’s future is bright. “This is an amazing constellation of assets,” he says, waving the presentation. “We’ve invested $7 billion, millions of hours. But public markets aren’t always the most patient.”

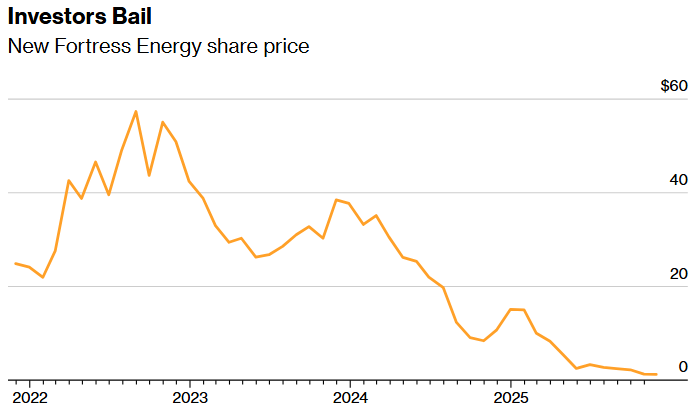

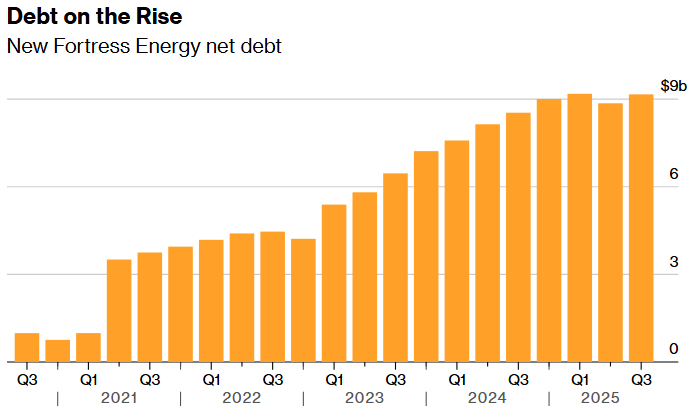

Seven years ago, when NFE listed on the Nasdaq, it promised to shake up the staid market for LNG, a cheaper, cleaner alternative to the oil and diesel that are still in widespread use to generate electricity in poorer countries. LNG is made by cooling natural gas to -260F (-162C), which compresses it to a 600th of its original volume. Edens and his colleagues had come up with a new method for building the hulking terminals where the liquefaction and export take place, which they pledged would be quicker and cheaper than how everyone else did it. They gave their process the snappy moniker “Fast LNG.” Investors and lenders lapped it up, pouring billions of dollars into the business. By 2022, NFE had a market cap of $9.5 billion.

Since then the stock price has plummeted from $60 to around $1 as the company has lurched from one problem to the next. The first Fast LNG export site, off the coast of Altamira, Mexico, was beset by construction issues, leading to long delays and ballooning costs. It’s now operational, but last year investors sued NFE and its executives for allegedly misleading them over how much progress they were making, claims the defendants have denied. The case is ongoing.

Source: Bloomberg

Meanwhile, NFE’s Nicaragua import terminal, which was originally scheduled for completion in 2021, has yet to be switched on; the company just sold its facility in Jamaica to pay down debt; one of its new import facilities in Brazil doesn’t have any customers lined up; and in Puerto Rico, even after securing a new deal to supply the island with LNG, Edens is still scrambling to patch up his relationship with the government.

In Edens’ telling, the difficult part—building the export and import terminals and power plants underpinning NFE’s business—is largely complete, paving the way for cash to finally start flooding in. He acknowledges it all took longer and cost more than anticipated, but he says the market is seriously undervaluing the company. Edens attributes many of NFE’s difficulties to the decision to go public too early, leading to unnecessary external pressure. Markets “often struggle to properly value projects until they’re turned on and generating revenue,” he says.

Some former employees (there’s no shortage: Two-thirds of NFE’s staff have left or been laid off in the past year), however, describe a company in perpetual crisis, run by a gifted salesman who’s proved more adept at attracting capital and winning contracts than at delivering on those commitments. Holders of NFE’s $9 billion of distressed debt are certainly running out of patience—some have taken to calling the company No F—ing Exit. With some NFE bonds currently trading at roughly 30¢ on the dollar, Edens is talking to creditors about the possibility of restructuring the company through a UK process known as a scheme of arrangement, which would involve converting some of the debt into equity and slashing the interest on what remains. That would allow NFE to continue as a going concern, though bondholders could decide they no longer want Edens at the helm. Another alternative would be declaring Chapter 11 bankruptcy and selling off the assets.

Source: Bloomberg

“It’s a very important time for the company,” Edens says, before donning a hard hat and leading a tour of the facility. If he manages to turn NFE’s fortunes around, it will be up there with the Bucks’ 2021 NBA championship, its first in 50 years, in terms of professional achievements. If he doesn’t, it will go down as one of the biggest corporate failures in recent history.

Natural gas provides about a third of the world’s energy. Once extracted from underground or beneath a seabed, the gas is delivered to consumers via high-pressure steel pipelines. But the pipe network doesn’t cover everywhere, and there are limits to how far the fuel can be pumped. Liquefying it allows it to be transported on massive ships equipped with specially built cryogenic tanks. The US is the world’s largest LNG exporter (a result of the fracking and shale explosion of the 2000s), followed by Australia, Qatar and Russia. When it reaches its destination, LNG is heated up and brought back to a gaseous state—“regasified.” The gas is given an odor to make it detectable in case of leaks and pumped into the local transmission system.

The industry’s biggest challenge is building the facilities that convert gas into LNG. These vast export plants, which in the US dot the coast of Texas and Louisiana, are constructed by armies of specialist workers over a period of years and can cost tens of billions of dollars. The cooling takes place in what’s known as a cold box, which relies on a heat exchanger system not dissimilar to that found in a home’s HVAC unit, at thousands of times the size. Once liquefied, the fuel is stored in tanks as tall as a 15-story building at a constant -260F, requiring around-the-clock monitoring. Shutdowns and accidents aren’t uncommon; many facilities have their own fire department. All this helps explain why the market has traditionally been dominated by nation-states and oil majors such as Exxon Mobil Corp. and Shell Plc. Companies that build LNG plants tend to sell the fuel via generationally long contracts—as long as 20 years—to persuade financiers to commit the capital required. Barriers to entry, in economics parlance, are high.

The idea for NFE struck Edens after Fortress Investment Group LLC, the private equity firm he co-founded, bought a train line in Florida in 2007. (The current iteration of the train, which runs between Orlando and Miami, is called Brightline.) When the firm settled on LNG as the train’s fuel source—briefly; it now runs on biodiesel—he saw the potential for a new business. “We’ve had lots of success in managing money, making investments,” Edens says. “I wanted to do something that had a meaningful and tangible impact on the world.”

NFE built a micro liquefaction facility in 2015 and the next year started exporting surplus fuel not used by the railway to Caribbean markets. Then it built import terminals—where LNG is heated and turned back into gas—in Puerto Rico, Mexico and Jamaica, and also acquired an existing facility in Brazil. It hired traders in London to buy cargoes of LNG in the market and leased tankers to ship it. LNG tankers can be almost a thousand feet long, and shipments are typically worth tens of millions of dollars. In the early stages of the war in Ukraine, when Europe was looking to rapidly replace Russian natural gas, a shipment could fetch as much as $100 million.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, when demand plummeted for energy of all kinds, NFE announced an investment in a green hydrogen business. Later the company pivoted to data centers. Edens can be demanding and mercurial, say former NFE employees, who requested anonymity owing to the company’s difficulties. They recount executives being dispatched at short notice to Sri Lanka, Mauritania and Ireland to win business, then berated when nothing came of it. One former executive recalls dreading being summoned to the boss’s Manhattan office—a situation not helped by the large painting of a wolf devouring its prey hanging on the wall.

“The media loves to elevate the voices of former employees,” Edens wrote in an email response to questions. “But those who quit and walked away should not drive the narrative or define our story.”

It was during the pandemic that Edens and his team struck upon the Fast LNG concept that would propel NFE to the status of investor darling. At the time, a large majority of LNG terminals were based on land, but some forward-looking companies had started putting them offshore, on huge vessels, removing the hassle and cost of acquiring real estate. NFE proposed to slot liquefaction terminals onto disused oil rigs, which could be picked up for next to nothing. Terminals would be identical, essentially interchangeable; cost efficiencies would follow.

Some in the LNG world were skeptical. Edens insisted Fast LNG would change the industry and made it the company’s primary focus, saying he hoped to get the first facility operational by 2022. The plan was to locate the maiden plant off the coast of Louisiana. When no permit was forthcoming after a year, Edens changed tack. In July 2022, NFE announced it had struck a deal with Mexico’s state utility to locate its first export facility off Altamira, with gas arriving through a 500-mile-long undersea pipeline from Texas. The terminal, spread over three separate rigs, would be built at a shipyard in Corpus Christi, Texas, then towed down the Gulf of Mexico.

In September, NFE issued a press release saying it hoped to complete the project by the next March. The plan was to follow that with four additional Fast LNG units in quick succession. “Utilizing a highly skilled workforce,” NFE had “developed an efficient and repeatable construction process—essentially an FLNG factory—that substantially reduces the cost and time to build incremental liquefaction capacity,” the company wrote. Two months later, NFE held an investor day at the shipyard, where two dozen or so finance types were given hard hats and shown around industrial-scale machinery by a long-haired engineer in coveralls. It was a hit, as was NFE’s announcement the same week that progress was so good the company was increasing its earnings guidance for 2023 to $2.5 billion, from $1.5 billion.

“We urge investors (who may have been waiting on the sidelines before) to take a serious look at NFE now because Fast LNG, we believe, is coming soon and the broader market doesn’t likely fully appreciate the potential upside,” one analyst wrote. Another said he’d come away from the site visit with “increased confidence” in NFE’s ability to meet its construction targets. He increased his target price for the stock by $10.

By the following week, NFE’s shares had risen 7%, almost to their historical peak. NFE then borrowed an additional $700 million and announced a bonus dividend worth $630 million. “Our business is now generating significant, stable, and growing cash, which we believe affords us the ability to both retain capital necessary to grow and return excess capital to shareholders,” Edens said in a December 2022 press release. As the biggest shareholders, he and his family received $217 million, more than the company’s profit for the previous year.

Behind the scenes, though, NFE was starting to flounder. Construction of the Altamira export terminal was taking longer and costing more than anticipated. (The final cost was about $3.5 billion, more than three times the original estimate.) NFE pushed the expected completion date from March to May 2023, then October, then early 2024. Similar delays were occurring at the import terminals in Nicaragua and Brazil. As for developments in Angola and Mauritania that were announced enthusiastically in press releases, they never got going.

Former executives say Edens had a habit of telling investors and prospective customers what they wanted to hear without consulting engineers and project managers on the ground. On earnings calls he’d talk about how he had “tremendous visibility,” and how his estimates of future income were “not really forward-looking” because they were based on “the business flows and the transactions that we have in hand.” Then, the following quarter, he’d move the goalposts, and the share price would tumble.

“There’s a saying we live by—it’s literally on our office wall: nothing exceptional comes from reasonable expectations,” Edens wrote in an email by way of explanation. “It’s simply a way to motivate others to suspend disbelief and get big things built.”

With pressure mounting, Edens and his team took the decision in the summer of 2023 to transport the Fast LNG plant from Corpus Christi to Altamira before it had undergone commissioning, the rigorous final testing of systems and equipment. NFE marked the milestone with a video showing a rig as tall as an office block, complete with living quarters and a helipad, being pulled across the ocean by five tugboats that looked minuscule by comparison. It was an arresting image, but commissioning on the water rather than onshore created logistical headaches and ended up adding to the delays. In February 2024, after another disappointing set of earnings, Edens pushed the timetable back once more. “While it’s been a little bit delayed,” he said on an earnings call, “it’s important to note that it still would be the fastest LNG installation in the history of the planet.”

Around midday on April 26, an aluminum pipe inside the cold box exploded during a pressure test. The site was evacuated, and several workers were hospitalized. Repairs dragged on. Finally the first LNG cargo ship set sail from Altamira on Aug. 12. It should have been a moment of celebration for Edens and his team. But earlier that week the company had put out a press release slashing its earnings guidance in half, leading NFE’s shares to fall 24%. There was more bad news to come.

On Sept. 17, 2024, investors filed the class-action lawsuit in New York, alleging that New Fortress and its executives intentionally and repeatedly misled the market about progress at Altamira and other locations, a form of securities fraud. The suit contrasted Edens’ and his executives’ upbeat public statements with a damning picture of what was happening on the ground, drawn from interviews with a dozen unnamed former NFE employees who’d worked on the project. Pipeworkers, project managers and engineers reported “endemic” delays, hazardous working conditions, “poor planning” and “chaotic” mismanagement. One described Edens’ decision to commission the facility on the water as “insane.”

The most shocking allegation related to the November 2022 investor day in Texas. According to the manager responsible for commissioning at the time, NFE had “pulled the main turbines from the manufacturer’s (Siemens) factory early—three months before they were done—just to make it look like Defendants were further along to attendees at the investor day presentation.” The whole event was “staged to create an illusion of progress,” the former manager said. (Edens denies this happened, describing the allegation as “ridiculous.”)

NFE rejected the allegations in the lawsuit, writing in a filing that Edens and his colleagues “expressly and continuously disclosed that its projected milestones were simply estimates.” (Corporate officials who make forward-looking statements in good faith are protected from prosecution by so-called safe harbor provisions.) NFE added that the Altamira facility was “successfully built and continues to drive value for the Company’s stockholders.” A motion by NFE’s lawyers to dismiss the case is being considered by the judge. “I’ve never sold a share!” adds Edens, refuting the suggestion that he profited from his overoptimism. As for the decision to pay a large dividend when most of the assets were unbuilt, he says that was consistent with his understanding of the business’s prospects at the time.

Earlier this month, after some to-ing and fro-ing, NFE announced it had secured a seven-year contract worth $3.2 billion to supply Puerto Rico with gas from Altamira. It was a welcome development but smaller than the 20-year deal originally mooted, and the news barely made a ripple in the markets. Next up, there’s the matter of finding long-term buyers for the power produced by the Brazilian terminal in Santa Catarina and getting Nicaragua operational. Both of those efforts, Edens says, are “nearly complete.” Soon, he says, gas will finally start flowing, along with NFE’s profits.

As for the plan to build more Fast LNG export terminals, that’s been shelved, at least for now. According to Edens, that’s a natural consequence of changes in market fundamentals: LNG prices are now so low that it’s just as cheap to buy cargoes in the markets as it is to produce it at export terminals like Altamira. Others see it as more of a capitulation. “The fact is that NFE’s ambition was not matched with technical and execution capabilities,” says Richard Pratt of the consulting firm Precision LNG. Pratt describes the whole Fast LNG concept as a “white elephant.”

If the business is to have any kind of future, Edens and his bankers must first reach an agreement with NFE’s various creditor groups. On Nov. 15 bondholders agreed to hold off receiving their latest interest payments for a month, buying Edens a little more time to build consensus around a restructuring plan and save the company. Adding to his stress, Brightline, the Florida train operation, is undergoing its own restructuring after failing to service its debts. Considering the stakes, Edens seems relaxed about it. “Obviously it’s not ideal, but this is a circumstance that many companies have been through before in one way or the other,” he says of NFE’s predicament. “There’s a tremendous amount of asset value. The company is literally on the 1-yard line.”

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS