Green hydrogen was meant to clean up dirty sectors like steel and shipping. But costs are high, investment is falling, and projects are stalling. Is it the fuel of the future — or a climate bet gone bad?

By Keira Wright and David R Baker

A train powered by fuel cells which convert hydrogen to electricity, in Wolfsburg, Germany. Whether hydrogen will be the crucial piece of the puzzle to reduce greenhouse gases or an overpriced, overhyped distraction is still being debated. Photographer: Peter Steffen/dpa/picture alliance/Getty Images

The basic strategy in the fight to limit climate change is to power everything with electricity generated from wind, solar or other clean sources.

But there’s a problem: Some things can’t easily run on electricity. Think steel mills, cement plants and long-distance passenger jets. They need a clean fuel that can be stored and burned, sometimes at high temperatures. This is where green hydrogen comes in. Depending on who you ask, this controversial technology is either a crucial piece of the puzzle to reduce greenhouse gases or an overpriced, overhyped distraction.

Governments and companies around the world have backed the vision. Australia, for example, has ambitions to be a global leader in hydrogen by 2030. But investors are now backing out of projects, making that goal increasingly unlikely. The future of green hydrogen also faces uncertainty in the US after the Trump administration slashed funding for clean energy projects.

What’s the advantage of hydrogen?

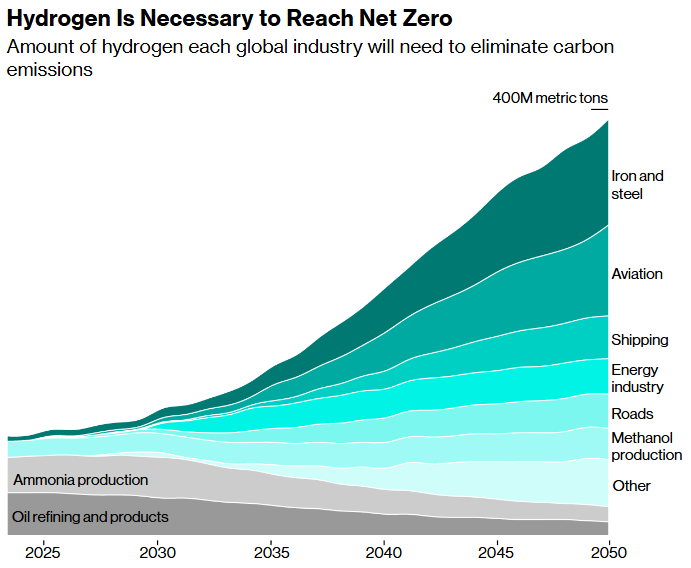

Electricity can be used to power most things, but it’s not yet a practical option for some industrial processes. Making steel from iron ore or producing cement requires extreme heat — something electricity can provide in theory, but not yet cost-effectively at scale. Similarly, planes and boats can run on electricity for short hops, but batteries that could power long-distance trips don’t yet exist. Hydrogen could help to clean up these hard-to-abate sectors.

Hydrogen is produced using energy, and when that energy comes from renewables — emitting no greenhouse gases — it’s called “green” hydrogen. It can then be burned directly as a fuel, for example, in high-temperature industrial furnaces. Alternatively, it can be used in a fuel cell, which generates electricity through an electrochemical reaction instead of combustion. Aircraft, cargo ships and trains could, in theory, run on fuel cells paired with hydrogen tanks, offering a way to cut emissions without lengthy recharging stops.

While other green fuels like biofuels or synthetic alternatives are emerging, green hydrogen is one of the few zero-emission options being seriously considered at scale for these applications.

Source: BloombergNEF

How is hydrogen made?

Hydrogen is the universe’s most abundant element, but it’s typically bound up in compounds like water or methane. To be used as a fuel, pure hydrogen must be extracted from these materials.

One common method is steam methane reforming. This involves reacting methane — usually natural gas — with very hot steam to produce hydrogen and carbon monoxide. It’s the most widely used method today, but because it emits large volumes of carbon, it’s not considered climate-friendly. The result is known as gray hydrogen, but if the carbon emissions are captured and stored, it’s classified as blue hydrogen.

Another method starts with water. A machine called an electrolyzer splits water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen using electricity. If that electricity comes from renewable sources like wind or solar, and therefore doesn’t emit any greenhouse gases, then it’s deemed green hydrogen.

There’s also geological hydrogen, which exists in pockets underground, though only a handful of large, concentrated deposits have so far been discovered. Momentum is, however, building in the sector to search for substantial reserves that could be extracted — which would be far cheaper than stripping it from water or natural gas.

What’s the state of the green hydrogen industry?

Demand and usage of hydrogen as an energy source remain limited. Low-emissions hydrogen — including both green and blue — accounted for just 0.7% of total hydrogen consumption in 2023, according to the International Energy Agency. Meanwhile, Bloomberg’s commodities and disruptive technologies research provider BloombergNEF expects that green hydrogen is unlikely to become price-competitive with fossil-based alternatives like gray hydrogen before 2030, and even then only in select markets.

Current usage is concentrated in sectors already using hydrogen, such as oil refining and fertilizer production. The full-scale use of hydrogen for other applications such as steel production or blending it into natural gas grids is still being tested or in its early stages.

A handful of trains around the world are now powered by hydrogen, including one that was launched in Germany in 2018 and another in Japan in 2022. Meanwhile, Swedish steelmaker SSAB is collaborating with Volvo to make green steel car parts produced using hydrogen. It delivered its first truck parts to the automaker in 2021 and plans to be making fossil-free steel at a commercial scale by 2026. In Australia, a production facility now blends renewable hydrogen into a natural gas grid that serves around 4,000 homes and businesses.

While hydrogen-powered fuel cell vehicles do exist, the International Energy Agency estimates there are fewer than 100,000 on the road — a fraction of the 40 million battery-electric vehicles worldwide. Uptake has been limited by sparse refueling infrastructure, high costs and lower energy efficiency compared to batteries.

Meanwhile, hydrogen has already been used to power aircraft in multiple demonstration flights, and the global aviation industry has pledged to achieve net zero by 2050. But with industry leaders like Airbus postponing their plans to adopt green fuel, widespread commercial usage likely remains many years away.

Why hasn’t green hydrogen usage become mainstream?

Producing hydrogen at scale requires vast amounts of renewable electricity and costly electrolyzers, and its adoption would require the end user to retrofit or replace equipment — a steel mill can’t just swap coal for hydrogen, and gas-fired power plants can’t burn it without upgrades. That upfront investment has made many developers hesitate.

Over the past decade, green hydrogen has made clear technical strides — modern electrolyzers are now larger, more efficient, and cheaper to produce, particularly in China. But production is still heavily reliant on subsidies and can’t compete with the lower cost of using fossil fuels.

Hydrogen storage and transportation also remain major technical and financial hurdles. At its normal temperature hydrogen takes up a lot of space, making it impractical for long-distance transport. It makes most sense to compress it into a gas or transform it into a liquid for transport, but both of these processes and storage methods are costly, energy-intensive and relatively inefficient.

To store hydrogen as a gas it must be compressed and held in high-pressure tanks, which requires significant energy and poses combustion and leakage risks. To get to a liquefied form, hydrogen requires extreme cooling and then must be stored at very low temperatures inside cryogenic tanks that minimize evaporation. The process consumes up to 40% of its original energy content, according to BloombergNEF. There are other options such as storing the fuel in underground salt caverns, but that’s only possible in certain geological formations and doesn’t solve the problem of transporting it.

Transporting hydrogen over long distances also poses challenges. It can be transported via pipelines in a similar way to methane but leakage can occur, contributing to greenhouse gases. Dedicated pipelines are scarce — just an estimated 5,000 kilometers exist globally, mostly serving industrial hubs — and building new ones will take years. Pipes are also susceptible to hydrogen’s embrittling effects on metal that can cause cracking.

Transporting it via ship is even harder. Hydrogen isn’t very energy-dense, even when compressed, so it would need to be shipped in very large volumes to be economical. In liquid form it’s too difficult to keep cold enough — the first-ever shipment of liquid hydrogen from Australia erupted in flames in 2022. Hydrogen is already shipped in denser, more stable forms such as ammonia and methanol, but both are highly toxic and pose environmental and safety risks if spilled.

Are countries still betting big on hydrogen?

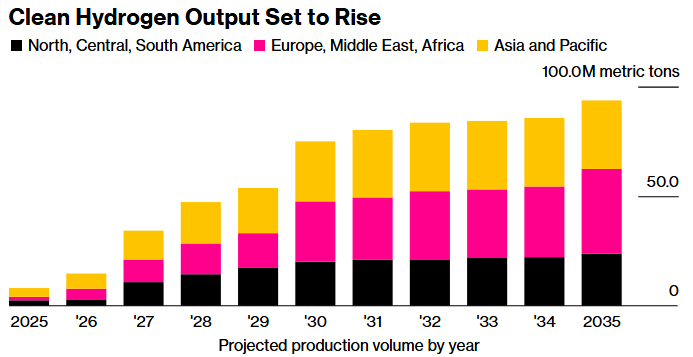

Green hydrogen has secured the most investment and interest by a wide margin compared with its dirtier counterparts, according to Nigel Rambhjun, a hydrogen analyst at independent energy research company Rystad. But investment is also slowing: global spending on clean hydrogen halved in 2024 to $24.3 billion.

Nevertheless, more than 60 countries have now published hydrogen roadmaps, and governments had earmarked at least $275 billion for clean hydrogen by March 2025, according to BloombergNEF.

The EU and its member states are leading the push, with $118 billion pledged as of March and new funding mechanisms like the Hydrogen Bank — a European investment vehicle — beginning to flow. Still, pipeline buildouts remain slow, 2030 production targets remain out of reach, and projects have been abandoned despite government support.

Outlook in the US has dimmed after the Trump administration passed a multitrillion-dollar tax bill that slashed funding for clean energy, including hydrogen. BloombergNEF now expects just 150,000 tons of annual green hydrogen capacity to qualify for subsidies by 2030 — a sharp drop from the 1.2 million tons previously forecast. That shift has rattled developers and cooled momentum in what was expected to become a top-tier hydrogen market.

In Australia, the ambition of becoming a green hydrogen superpower with a A$225 billion ($147 billion) project pipeline — the largest globally — has started to falter. Major developers such as BP have pulled out of projects and the country’s pipeline is now shrinking. While federal subsidies remain in place, most funding is tied to proving commercial viability upfront — a tough ask in today’s market.

In contrast, China and India are pressing ahead in a bid to dominate low-cost hydrogen production. China — the world’s largest hydrogen consumer — is rapidly growing its manufacturing and deployment capabilities, with the goal of self-sufficiency for its domestic market. India has set ambitious targets under its $21 billion Green Hydrogen Mission and is offering incentives to boost domestic output.

Is demand for green hydrogen expected to pick up?

High costs have kept global demand for green hydrogen low in the short term. Carbon prices are too low to incentivize the uptake of clean hydrogen or derivatives like ammonia, even in the European Union. Still, demand for clean hydrogen is expected to grow in the long term.

The market for gray hydrogen — which accounts for 90 million tons per year, almost all the hydrogen consumed today — is projected to decline as green molecules become cheaper over time. By 2050, clean hydrogen is expected to account for 73 to 100 percent of total hydrogen demand, according to McKinsey.

Source: BloombergNEF

Note: Projections based on announced projects.

What’s at stake?

Whether green hydrogen becomes a pillar of the global energy system or fades into a niche solution will depend on what happens in the next few years.

If hydrogen becomes cheap and abundant enough, the potential payoff is huge. Hydrogen could help cut billions of tons of carbon emissions, accelerate the energy transition, and reshape global fuel markets.

But if the economics don’t improve fast enough, the risk is that governments and companies will have poured hundreds of billions of dollars into a solution that never scales and collapses under the weight of its own hype.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS