An offshore oil drilling platform in Norway. Photographer: Carina Johansen/Bloomberg

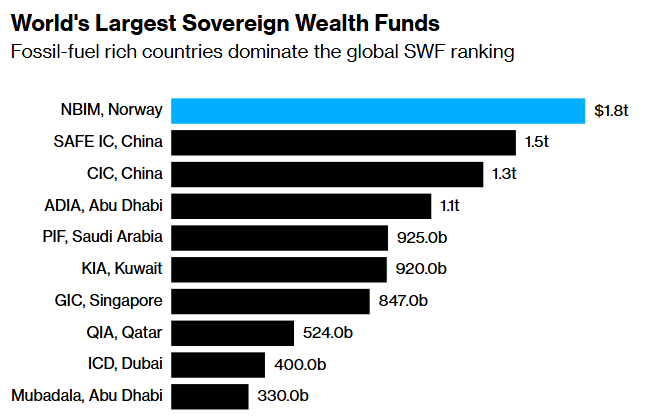

Of all the world’s sovereign wealth funds, Norway’s is one of the most unusual. These giant, state-linked investment vehicles tend to pick and choose what assets they hold to manage risk, maximize returns and further national strategic interests. Not so with Norges Bank Investment Management, which largely tracks global indexes in order to generate an income from the country’s oil and gas revenues.

Launched in the early 1990s to invest mostly in bonds, the fund has grown to become the largest of its kind by acquiring small equity stakes in thousands of companies across the world. The fund’s $1.8 trillion of assets generate far more income for the Nordic country’s 5.5 million population than its oil and gas industry.

But it’s passive approach to investing the nation’s wealth leaves it with few tools to adapt to the ebb and flow of global capital. This was underscored in April when it reported its biggest loss in six quarters amid the market turmoil unleashed by US President Donald Trump’s threatened trade tariffs. The setback revived a debate in Norway over how to shield the fund from future shocks.

Source: Global SWF

Note: Chart ranks assets under management by the latest period USD figure if available, estimation by Global SWF otherwise

What’s special about Norway’s sovereign wealth fund?

The fund stands apart from many of its peers due to its strict investment rules.

Firstly, it must always invest outside Norway — a rule designed to avert the risk of “Dutch disease,” where resource wealth can end up destabilizing the domestic economy.

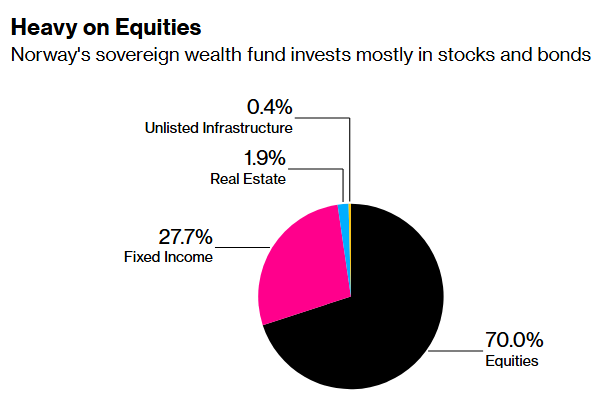

Whereas wealth funds in many other nations act partly to stimulate domestic industries or invest strategically to enhance a country’s soft power abroad, NBIM has limited scope for active investing. The equity portion of the fund, which makes up 70% of the total, holds stakes in the 8,700 listed companies in 44 countries that comprise the FTSE Global All Cap index. As a result, it now owns about 1.5% of listed stocks worldwide. The fixed-income portion of the fund tracks Bloomberg Barclays indexes, with 70% allocated to government bonds and 30% to corporate securities.

Other wealth funds are freer to adjust their priorities and how they achieve them. The Abu Dhabi Investment Authority is increasingly focused on private equity and data-driven investing, while Mubadala Investment Co. plays a central role in diversifying the emirate’s economy through stakes in health care and finance. Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund is leading the kingdom’s Vision 2030 transformation plan, with major bets on mining, gaming and technology. Singapore’s GIC Pte is ramping up its US exposure and taking on more risk in private markets.

What are the origins of Norway’s wealth fund?

Norway discovered significant oil and gas reserves in the North Sea in 1969, and today is western Europe’s largest producer of the fossil fuels. Anxious to avoid the instability, corruption and weak economic growth experienced in other resource-rich economies, the government imposed heavy taxes on the energy sector and placed strong regulatory controls on the industry. In 1990, after years of political debate, Norway’s parliament created the Petroleum Fund to ensure that oil revenues would benefit both current and future generations. The first capital transfer to the fund was made in 1996. As it spread its investments across the world, it shifted gradually to explicitly supporting the national pension system, and was renamed the Government Pension Fund Global in 2006. The fund is managed by NBIM, the asset management arm of Norway’s central bank.

How did Norway’s wealth fund get so big?

Early on, the fund was padded out with cash from oil taxes, licensing fees and profits from the state energy company. Initially limited to investing in bonds, its mandate expanded over time. Today, it’s the world’s biggest single owner of listed shares.

The government can’t just grab what it wants from the fund. No more than 3% of the fund’s value can be diverted annually to the national budget, a rule intended to preserve the wealth for future generations. The rest is kept for new investments.

When comparing its investment returns with those of other sovereign wealth funds, the Norwegian fund achieved a relatively average performance over the five years to 2023, returning 7.45%, according to research consultancy Global SWF. That’s less than Abu Dhabi fund Mubadala, at 10.1%, and China Investment Corporation, with 8.6%, but higher than the 4.5% return for Singapore’s Temasek and 5.2% for the Korean Investment Corporation.

How has the Norwegian fund’s mandate evolved?

The fund has increases its investments in equities over time and has added real estate and renewable energy infrastructure to diversify its portfolio. It has also emphasized sustainability and responsible investing, with a growing focus on environmental, social and governance factors — an approach that’s not changed in response to the Donald Trump administration’s backlash against “woke capitalism.”

Source: Norges Bank Investment Management

Note: Allocation at the end of March

What are the Norwegian fund’s ethical investing principles?

Since 2004, the fund has operated under ethical guidelines set by the finance ministry and approved by parliament. An independent Ethics Council oversees the guidelines, which prohibit investments in companies involved in “gross corruption” or serious violations of human and labor rights, or that contribute to severe environmental damage. They also exclude companies that produce certain weapons, such as nuclear arms and cluster bombs.

Some 67 companies had been dropped from the fund by the end of 2024 due to their conduct. These included Indian firm Adani Ports, for its business with the armed forces of Myanmar, and the communications company Bezeq, for its activities in the Israeli settlements in the West Bank, which are illegal under international law. A further 104 companies have been removed from the fund because of what they sell: The fund’s guidelines prohibit investments in the cannabis industry, tobacco and coal. It also avoids companies that are responsible for “unacceptable greenhouse gas emissions” — a paradoxical stance given that the fund itself is infused with income from the sale of fossil fuels.

Will the Norwegian wealth fund change its investing mandate?

NBIM reported a 0.6% loss on its investments — equivalent to $40 billion — in the first three months of 2025. The market downturn has deepened since then in response to President Trump’s sweeping US tariffs, sparking a debate in Norway over how to protect the fund from a more unpredictable economic climate. About 40% of the fund’s equity holdings are in the US, and some Norwegian politicians say it should shift more investments to Europe so it’s less exposed to volatile US markets. US bonds made up 9% of the fund’s holdings at the end of 2024. Norway’s finance minister, former NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg, has said the fund remains committed to its long-term strategy while “continuing to assess risk management options.”

Norway’s conservative opposition has proposed revising the fund’s guidelines to allow it to buy shares in companies that make nuclear weapons. The current restriction precludes the fund from investing in much of the European arms industry, which is in line for a profit windfall as governments embark on the biggest rearmament since the Cold War in response to Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Norway currently supplies about 30% of Europe’s gas, and some politicians have called for more cash transfers from the fund to support the government in Kyiv, arguing that Norway’s oil and gas industry has made massive profits from the European energy crisis that followed Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

The fund’s leadership has argued repeatedly for adding private equity to its investments, a call that the finance ministry has rejected, wary of the sector’s high fees and relative lack of transparency. The debate is ongoing.

What does Norway do with the wealth fund’s available profits?

Some of them go to support Norway’s extensive welfare system, which provides free education and health care, highly subsidized child care and generous sick leave. Norway ranks third on the UN’s global Human Development Index, after Iceland and Switzerland. In 2024, transfers from the fund accounted for roughly 20–25% of the national budget. The government has proposed to transfer 50 billion kroner ($4.85 billion) from the fund to support the government of Ukraine.

What’s the fund’s impact on Norway and the world?

The fund has been a financial buffer that enabled the country to weather fluctuations in oil prices and the economy and maintain the country’s fiscal stability. It has furthered Norway’s soft power by promoting sustainable business practices worldwide. In June 2024, the fund voted against Tesla Inc. Chief Executive Officer Elon Musk’s record high compensation package of $56 billion that’s since risen in value and has been contested in court. The fund issues its voting intentions five days before the annual meetings of the companies it invests in, and opposed board recommendations in 5% of shareholder votes in 2024.

— With assistance from Nandu Nair

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

What Excites and Worries LNG Exporters in 2026: Maguire