By Mitchell Ferman and James Herron

It’s been almost 25 years since BP Plc attempted to rebrand itself as “Beyond Petroleum” and adopt a more environmentally friendly image. But with a recent swing away from green energy toward its fossil fuel roots, “Back to Petroleum” might be a more appropriate tag line.

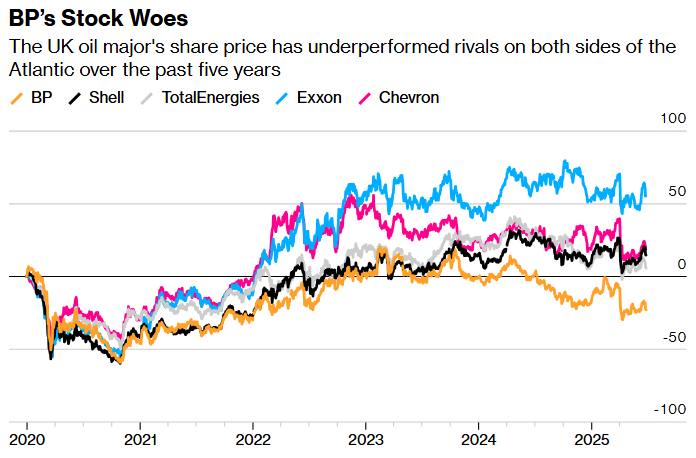

The shift comes as BP lags significantly behind its fellow oil and gas majors, due to a combination of corporate disasters, war, lackluster returns from its greener efforts and some bad luck. It could even be a takeover target, although rival Shell Plc has ruled itself out of the running for now.

Activist shareholder Elliott Investment Management has been turning up the heat, and BP management has laid out plans for a grand reset. The effort risks being blown off course if crude oil prices remain below $70 a barrel, with US President Donald Trump’s tariff war weighing on the outlook for oil demand and the OPEC+ cartel ramping up supply. This price level is the foundation of BP’s targets for improved cash flow and returns. By the company’s own reckoning, each $1 drop in oil prices wipes an estimated $340 million from its pretax profit.

Where did BP’s problems begin?

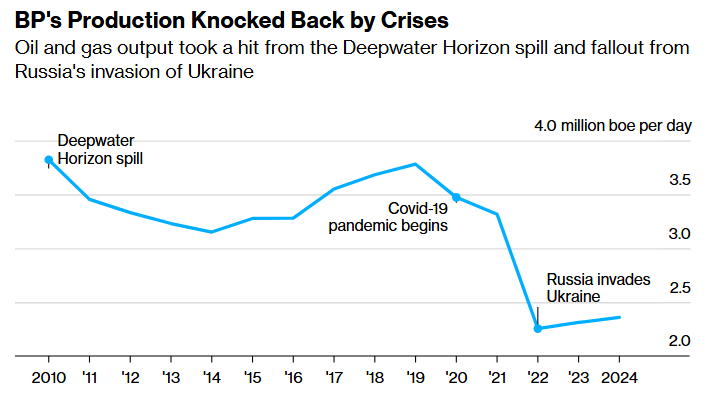

BP’s long decline was precipitated by the explosion aboard the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig in 2010, which killed 11 people and triggered the worst offshore oil spill in US history in the Gulf of Mexico. A federal judge found that the discharge of oil was the result of “gross negligence” and “willful misconduct.”

The company agreed to pay more than $65 billion in fines, environmental cleanup costs and compensation for thousands of businesses across several states. It’s still forking out for those damages today, at a rate of about $1 billion a year. BP shed more than half its value after the disaster, and its market capitalization has yet to recover.

Deepwater Horizon was only the first in a series of crises. There was also a bet on Russia that went awry. BP sold its stake in its Russian joint venture TNK-BP in 2013, in a deal in which it took 20% ownership of Rosneft PJSC, Russia’s largest oil producer. While for several years the gambit paid off, helping boost BP’s overall oil output, being the second-biggest shareholder in a company controlled by the Kremlin brought greater exposure to political risk.

The price of this became evident in 2022, when Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine led BP to abandon its stake in Rosneft and walk away from an asset worth around $25 billion that provided a third of its production.

Source: Bloomberg

Note: “boe” refers to barrels of oil equivalent.

What spurred BP’s venture into renewables?

ESG may have fallen out of favor in recent times, but a few years ago it was all the rage, and investors preoccupied with environmental, social and governance issues were pressuring fossil fuel producers to reconcile their activities with the Paris Agreement goal to limit global warming to 1.5C.

The architect of BP’s climate pivot was then-Chief Executive Officer Bernard Looney. The firm was among the first oil majors to embrace the idea of reaching net-zero emissions, announcing in 2020 an ambition to achieve this goal by 2050.

This coincided with the arrival of the Covid-19 pandemic, which triggered a slump in oil demand. In the early weeks of this crisis, consumption in the world’s biggest market, the US, fell to its lowest in at least 30 years, and there was speculation that global crude demand may have finally peaked. BP said it would aim to reduce its oil and gas output by 40% by 2030 versus 2019 levels, and rapidly scale up investment in renewables.

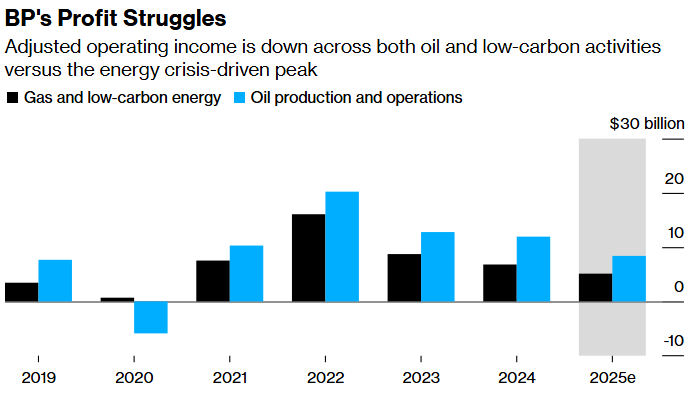

But then Russia’s invasion of Ukraine sparked an energy crisis and a surge in oil and gas prices. Fossil-fuel producers, including BP, raked in record profits. In many places, especially Europe, the conversation shifted from climate concerns to security of supply. In 2023, BP revised down its goal to lower oil and gas production by the end of the decade to a 25% cut.

Source: Bloomberg

Note: 2025 figures are mean consensus of analyst estimates as of June 26.

How has BP shifted its strategy?

The bumper profits from the energy crisis raised questions about BP’s decision to dial down its exposure to oil and gas. In the face of ongoing investor disquiet, the firm announced a major pivot back to fossil fuels in February 2025, ditching Looney’s vision of a low-carbon, fuels-of-the-future giant. It followed in the footsteps of the other supermajors, which recommitted more quickly to the hydrocarbon-focused strategies that fed their profits.

BP’s current CEO, Murray Auchincloss, said the company went “too far, too fast” due to what he called “misplaced” optimism over the pace of the energy transition. As part of a “fundamental reset,” BP scrapped the plan to shrink oil and gas production, and now intends to boost expenditure on these activities by nearly 20% to $10 billion per year through 2027. It will also slash annual spending on its energy transition businesses — which includes the likes of clean power, biofuels and electric vehicle charging — by about 70% to roughly $2 billion.

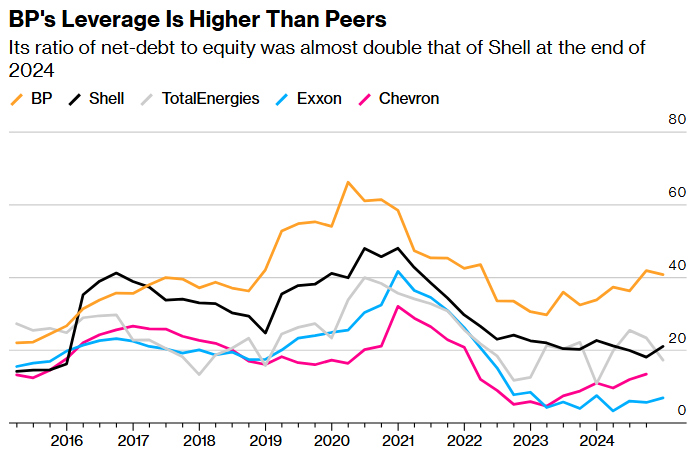

The strategy entails the divestment of $20 billion of assets by the end of 2027 too. This could include the Castrol lubricants business, which Bloomberg News reported could be worth around $10 billion. The proceeds could help alleviate a stretched balance sheet that has resulted in BP trimming its quarterly share buybacks at a time when most oil majors are maintaining shareholder returns.

BP’s ratio of net debt to equity — a measure of how much a business has had to borrow to stay afloat – was about 40% at the end of last year, far higher than for Shell, TotalEnergies SE, Chevron Corp. and Exxon Mobil Corp.

Source: Bloomberg

How has BP diverged from other oil majors?

Under shareholder pressure, all the supermajors eventually pledged to do more to address climate change. But a split emerged between the European and US companies in terms of how they approached the energy transition.

BP and Shell invested heavily to be at the forefront of the electrification of the global economy. They piled into industries that are looking to replace the use of fossil fuels, including wind and solar power and EV charging.

Exxon and Chevron, meanwhile, focused on technologies like carbon capture and hydrogen, which fit more neatly into energy systems already powered by fossil fuels. The American oil giants refused to kill the golden goose, increasing their annual oil and gas output by 15% and 9%, respectively, since the end of 2019.

If these strategies are judged by progress in share prices, it appears that investors are more impressed by the US blueprint. As of late June, Exxon’s shares had jumped by more than 50% since the close of 2019, while BP was down a fifth.

Source: Bloomberg

Note: Data as of June 26, 2025 and normalized with percentage appreciation since December 31, 2019.

Is BP at risk of a takeover?

Amid BP’s weakened state, it could be a takeover target, either acquired in its entirety or broken up and sold for parts.

Bloomberg News reported in May that Shell, whose stock market value is more than double that of BP, was studying the merits of a possible acquisition but was waiting for further stock and oil price declines before deciding whether to pursue a bid. Following a Wall Street Journal report in late June that discussions between the two companies were active, Shell released a statement saying that no talks had taken place and that it had no intention of making an offer.

That announcement bound Shell to the UK’s Takeover Code, largely preventing it from submitting a bid for BP for six months, although it could enter the fray sooner if BP receives an offer from another suitor or invites a takeover approach, or if there is a “material change” of circumstances. A combination of the two firms would be one of the oil industry’s largest-ever tie-ups, bringing together the iconic British majors in a deal that’s been discussed on and off for decades.

Other suitors could include a Middle Eastern oil company. Abu Dhabi National Oil Co. was evaluating whether it could buy some of BP’s key assets should the British firm decide to break up or come under pressure to divest more units, Bloomberg reported in June. A deal with a US buyer, while not out of the realm of possibility, is likely to be less palatable to UK regulators.

What does activist investor Elliott want?

BP’s lagging performance has put it in the crosshairs of the world’s most famous activist investor. When Elliott gets involved, companies sit up and take notice. In almost half a century of investing, the hedge fund has only lost money in two years of its existence. It’s shown it can kick out top management and even break up a firm.

Elliott has built up a stake of just over 5% in BP and has engaged in a campaign to return the major to its core oil and gas focus, demanding transformative changes, including substantial cost cuts, asset sales and an exit from renewable power.

While CEO Auchincloss said that he was confident after unveiling the turnaround program, Elliott reportedly sees the new plan as lacking in urgency and ambition, and could push for a more radical shakeup. A couple of decades ago, the idea of an American investor taking a stake in a storied British company and forcing it to revise its entire strategy would be pretty much unthinkable. It’s a testament to how vulnerable BP has become.

In an apparent nod to Elliott’s demands, BP announced in April that Chairman Helge Lund will be stepping down “in due course”, while Giulia Chierchia, executive vice president for strategy, sustainability and ventures, will leave the company and won’t be replaced. Both were seen as key backers of the failed 2020 plan to rapidly shift away from oil and gas into clean energy.

Not all shareholders are happy with the oil major’s refocus on fossil fuels. Legal & General Group Plc, a top-10 investor in BP, said in a post on its website in May that it’s “deeply concerned by the recent substantive revisions made to the company’s strategy” and the impact on climate commitments.

Is there a risk the oil majors get caught out by the race to net zero?

Oil companies are capitalizing on the pendulum swinging back toward fossil fuels amid concerns over energy security and the tailwind of US President Donald Trump vowing to “drill, baby, drill.”

But the focus on short-term profits could leave them exposed further down the line as the energy transition rolls on. There’s much debate over when, and if, oil and gas consumption will peak. OPEC forecasts oil demand will just keep rising, while the International Energy Agency expects the ceiling to be reached by the end of the decade. If a peak is indeed coming, doubling down on fossil fuels now could be a risky bet for all except the lowest-cost producers.

The Reference Shelf

Bloomberg News reports on what activist investor Elliott is trying to achieve at BP and why the strategy reset promised by Auchincloss is a make-or-break moment.

Bloomberg Green explores how BP’s crisis is the tombstone for Big Oil’s green pivot.

Bloomberg Opinion’s Javier Blas says that BP is asking shareholders to pay for its mistakes.

Read an explainer on how tariffs and OPEC+ are driving down oil prices.

— With assistance from Swetha Gopinath and Dinesh Nair

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS