- Energy Department enacted gas terminal moratorium in January

- Shale boom transformed US into world’s biggest LNG exporter

The oil and gas industry is zeroing in on the Biden administration’s moratorium on new liquefied natural gas export permits as the key policy they want changed under the next US president.

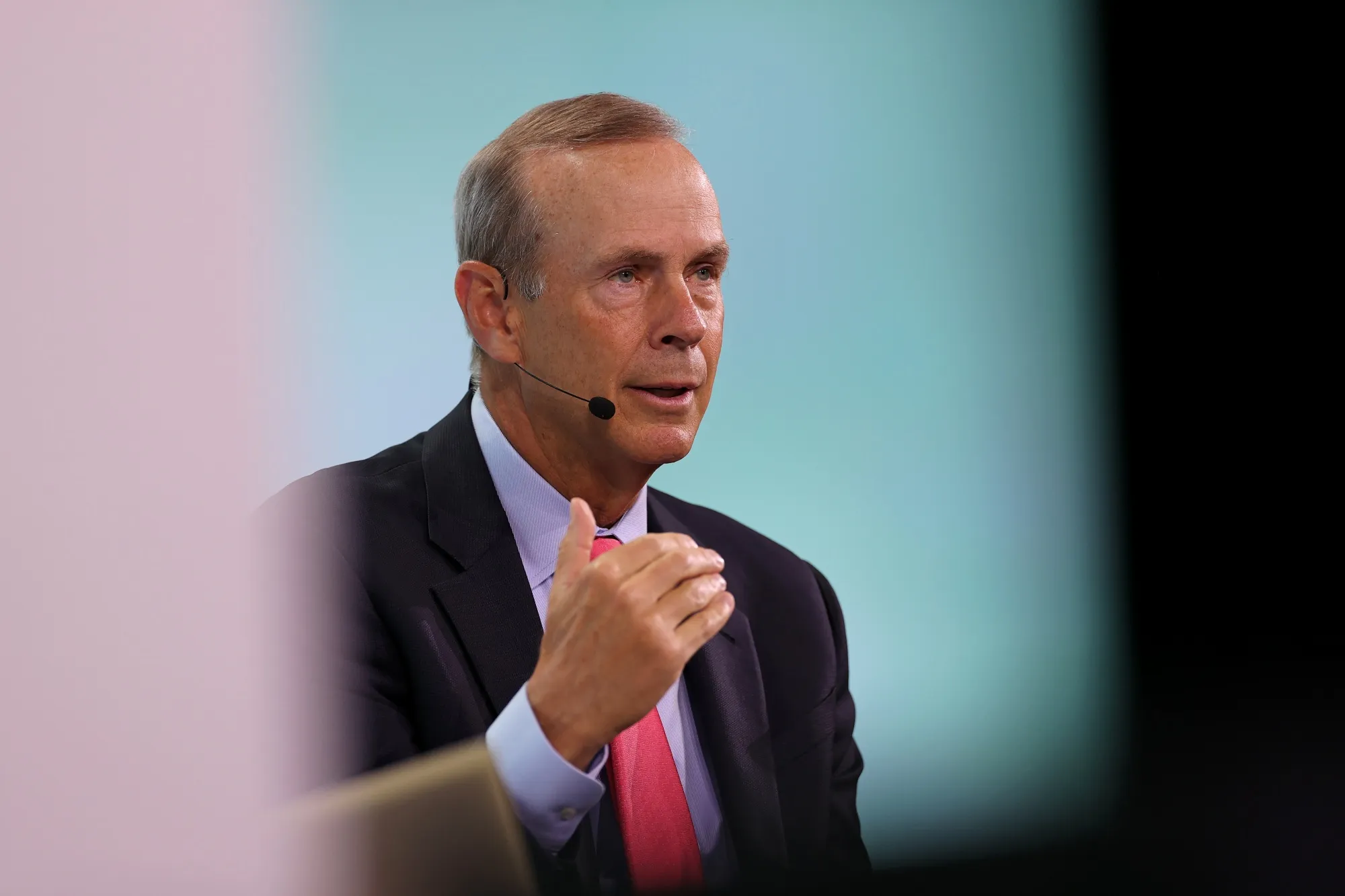

Chevron Corp. Chief Executive Officer Mike Wirth called on the administration to reverse the pause, labeling the policy as a failure that “elevates politics over progress.” The permitting halt, which went into effect earlier this year, will raise energy costs, threaten supplies for America’s European allies and increase emissions by slowing the transition from coal to gas, Wirth said in a speech at the GasTech conference in Houston Tuesday.

“When it comes to advancing economic prosperity, energy security, and environmental protection, an LNG permitting pause fails on all three,” he said. “The administration should stop the attacks on natural gas and embrace the benefits it’s already delivering around the world.”

The White House in January halted new licenses to export LNG, citing the need to more heavily scrutinize how the shipments affect the environment and national security. The ruling sent shockwaves through the industry, threatening to end a construction boom in terminals along the Gulf Coast that turned the US into the world’s biggest exporter of the super-chilled fuel.

“In Australia and the US, we’re seeing quite a bit of wobbliness around support for the industry,” said Meg O’Neill, CEO of Woodside Energy Group Ltd. “I do worry there’s going to be a long-lasting ripple of concern from key LNG-buying nations caused by the pause, even if the pause is short-lived.”

The industry has pushed back on the policy as it struggles with a surplus of natural gas, much of it a by-product of shale oil production. A federal judge in Louisiana lifted the temporary moratorium in July after several states sued. While the Energy Department is appealing the ruling, it also has granted an LNG export license following the decision.

“We can double down on the ‘either/or’ approach that dominates today’s discourse, which too often pits people and solutions against each other,” Wirth said. “Or we can evolve toward an ‘all-in’ approach that recognizes many solutions are needed.”

Both US presidential candidates have voiced their support for fracking, which makes up the majority of US oil and gas production. But some executives are still concerned about what Democratic nominee Kamala Harris may do in the White House, given her current role as Biden’s vice president. She hasn’t yet weighed in on whether she would reverse the LNG ban.

“We hope cooler heads do prevail, and maybe she’s sincere,” on her support for fracking, said Jack Fusco, chief executive officer of Cheniere Energy Inc., an LNG exporter. “I have to trust until I don’t.”

Wirth said the LNG pause was self-defeating because natural gas replaces more heavily polluting coal in power generation in many cases. In recent years, environmental groups have cast doubt on the claim, citing often-undocumented methane emissions in gas-gathering systems and the amount of power need to chill LNG.

The CEO said the emissions the US avoided by switching to gas from coal are more than double the reductions from all the wind and solar power added in the past 15 years, citing data from McKinsey & Co.

Making the switch to gas from coal globally “could represent the single greatest carbon reduction initiative in history,” he said.

It will also be vital for the development of artificial intelligence, he said.

“AI’s advance will depend not only on the design labs of Silicon Valley, but also on the gas fields of the Permian Basin,” Wirth said.

Even with the permit pause, the US is on track to double LNG export capacity by 2030, ensuring plenty of supply for allies thereafter, said Brad Crabtree, of the Department of Energy.

“It is not sufficient to assert that natural gas will displace more greenhouse-gas-intensive fuels like coal and oil,” he said. “The industry must demonstrate through concrete actions, a credible pathway that puts natural gas firmly on the trajectory to net zero emissions by 2050.”

Last year, participants in the United Nations Climate Change Conference agreed to phase down fossil fuels for the first time while also leaving room for natural gas as a transition fuel.

Even so, Wirth called for a “more balanced conversation about the future of energy.”

“These choices should be informed by realistic science and impartial data, untainted by advocacy agendas,” he said.

— With assistance from Ari Natter

(Updates with industry CEOs comments from fifth paragraph.)

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Where the Fight Against Energy Subsidies Stands – Alex Epstein