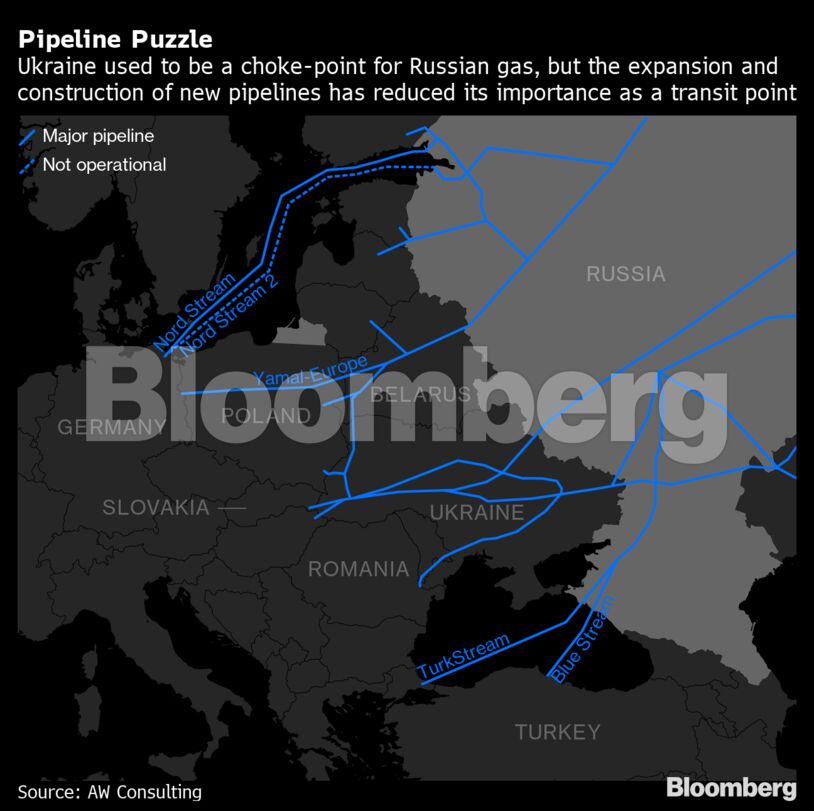

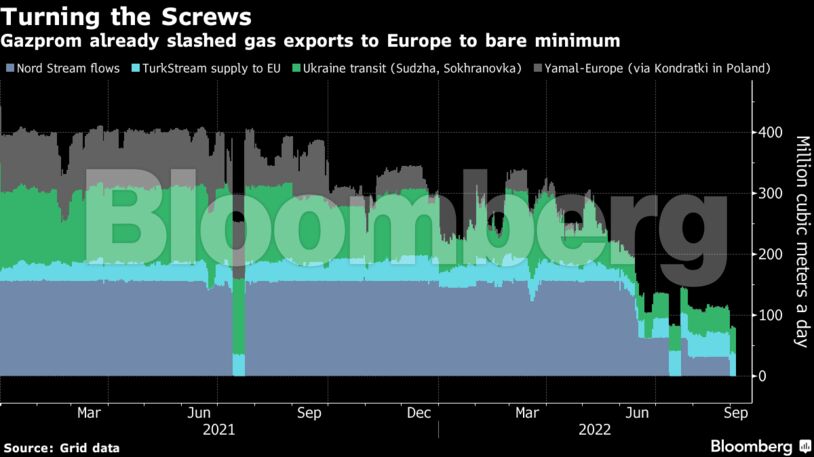

The link through Ukraine has already had part of its supply knocked out by the war, and could turn out to be the next to close as the conflict drags on and tensions escalate between Moscow and Europe. Even though some nations seen as friendly to the Kremlin are still receiving gas, Russia has progressively reduced flows to Europe’s biggest economies in retaliation for sanctions, plunging the region into crisis.

“There is always a risk of the Ukrainian corridor becoming unavailable as long as combat continues,” said Katja Yafimava, senior research fellow at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. “Given that as Nord Stream is switched off, the Ukrainian corridor is effectively the last standing route for Russian gas to Europe.”

Russia’s daily supply via Ukraine has been less than 40% of contracted transit volumes since mid-May after a key crossborder entry point — Sokhranivka — was put out of service. Ukraine’s grid operator said it lost control of the facility because of occupying forces in the east of the country, bordering Russia.

It leaves just one operating entry point in Ukraine via Sudzha. A halt there can’t be ruled out if there is physical damage of infrastructure amid military actions, according to Vyacheslav Kulagin, head of department at the Energy Research Institute in the Russian Academy of Sciences. Alternatively, Ukraine could decide to stop transit if it loses control of the territories that the link crosses, like it happened with Sokhranivka, Kulagin said.

Should supplies through Ukraine be shut down, it would cut in half Russia’s current total pipeline exports to the continent, which amount to some 80 million cubic meters per day. That would leave Gazprom sending gas via one leg of the TurkStream pipeline to a handful of European nations that didn’t severe business ties with Russia despite sanctions.

“If geopolitical considerations prevail, the TurkStream at first glance looks to be in a more privileged position than other pipelines,” said Sergei Kapitonov, a gas analyst at Skoltech Project Center for Energy Transition and ESG. “Its first and main target market is Turkey, viewed as a ‘friendly state’ in current Russian policy, and sales markets in Europe including Serbia and Hungary.”

The situation is already dire in Europe and politicians are rushing to cushion the fallout with drastic market interventions. EU energy ministers are meeting this Friday to hash out plans, which may include a proposal to put a price cap on Russian gas.

Such as move would risk further inflaming tensions with the Kremlin. Russian President Vladimir Putin warned on Wednesday that energy supply would be cut off to those that cap prices. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz again accusing Moscow of blackmail by shutting down supplies via Nord Stream and Putin saying it was “nonsense.”

Also read: Europe Looks Set for Energy Rationing After Russian Gas Cut

Nord Stream

Resumption of supplies via Nord Stream, the undersea pipeline to Germany, remains unclear. Gazprom has said the link can’t operate again until equipment malfunctions are fixed. But Siemens Energy, the manufacturer of turbines for the Portovaya compressor station, said that didn’t justify halting supplies, a view shared by Germany’s grid operator.

Even before the full stoppage, Nord Stream was only operating at 20% of capacity as four turbines were out of action because they need either major repairs or some servicing on site, according to Gazprom. Another turbine is currently stranded in Germany after maintenance in Canada. Gazprom has said “sanction entanglement” have stymied Siemens from providing maintenance.

The third major route, Yamal-Europe that runs through Belarus and Poland to Germany, has been out since May when Russia prohibited Gazprom from any cooperation with EuRoPol Gaz, the owner of the Polish section of the link. Not long before that the Russian gas producer halted supplies to Poland, as the country was among the first ones to reject Kremlin’s order to pay for pipeline gas in rubles.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS