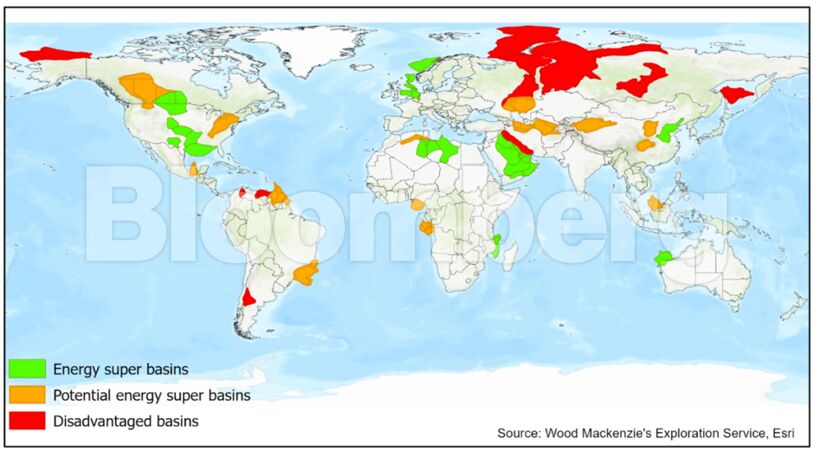

The shift will mean that several oil and gas fields that dominate the energy landscape today — from Alaska’s North Slope to Russia’s Yamal Peninsula and Venezuela’s Orinoco Belt — will be disadvantaged and face a flight of capital in the future. Such places have limited infrastructure to develop renewables at scale.

Meanwhile, regions with easier access to clean energy are likely to flourish. The US Gulf Coast and Permian Basin, Australia’s North Carnarvon and the Rub al Khali in the Middle East are positioned to be “future energy super basins” that will draw coordinated investment in drilling, renewables and carbon capture for decades to come, Latham said.

These new basins will benefit from oil majors that have already announced plans to reduce their direct emissions. The easiest way to do that is by powering drilling rigs and other oil field equipment with renewable energy, so advantaged basins will need to have access to plentiful wind and solar power.

In the long run, climate targets will pressure oil companies to also account for the emissions produced when oil and gas is burned. Carbon capture and sequestration is among the most promising ways for oil companies to do that, and energy basins that offer subsurface storage for injected carbon dioxide can help do that efficiently, Latham said. The consultancy expects carbon capture to grow to between 2 billion tons and 6 billion tons a year by 2050.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

Trump Is Scaring Republicans Away From Saving the Planet