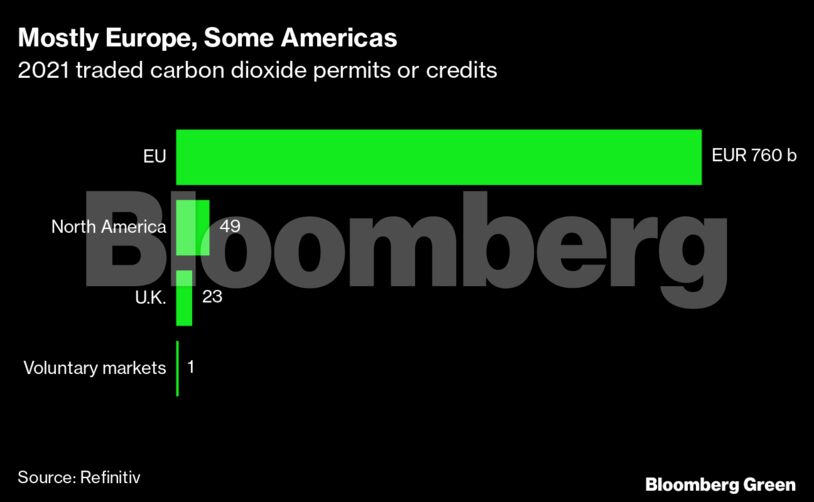

Then there are voluntary markets, created by independent entities, where corporations and institutions purchase credits for their own purposes. These totaled about 1 billion euros last year. Although relatively tiny, this amount will likely grow by orders of magnitude. Today’s voluntary market demand for carbon offsets is 127 million tons, a figure that could grow to at least 3.4 billion tons or as much as 6.8 billion tons by the middle of the century. Considering that global emissions today are just over 51 billion tons a year, offsets could be a significant part of deeply decarbonizing the global economy. But getting to that multi-gigaton scale will be about more than supply and demand.

Today there are numerous developers of offsets, thousands of projects around the world, different ways to verify CO₂ saved and multiple registries recording offset activity. In each of those domains, there is invention and competition—but also a high degree of uncertainty, which will limit expansion. As I wrote in January, solving that challenge will depend on new business models, new technologies and new markets, some of which could be very novel indeed, with blockchains and decentralized autonomous organizations and tokenized emissions credits.

Fundamentally, though, we can reduce it to two sets of issues: one around carbon itself and another around the markets that buy and sell it.

Carbon-related issues include measuring emissions reductions, verifying them, monitoring how durable and stable the reductions are, and registering them in a traceable way. These concerns are acute in carbon markets because credits’ effectiveness often depends on sensitive factors like changes in land use and forestry practices—when they’re not tied to old renewable energy assets that may not generate any real benefit at all. To coin a phrase, solving these problems is a matter of KYC: knowing your carbon.

Market issues include enabling transactions, maintaining records of them, providing credit and assurance, creating securities and, for financial institutions in particular, a much more established form of KYC: knowing your customer. These issues are not only not unique to carbon, they are integral to markets in general.

Clearly, bridging the two sets of issues will be essential for voluntary carbon markets to scale up massively. It will do no good to have carbon credits that cannot be verified or monitored, or credits that are verified but have no durable financial-market record, or transactions that do not clearly identify customers in ways that regulators can see. The problems need to be solved and their solutions tied together.

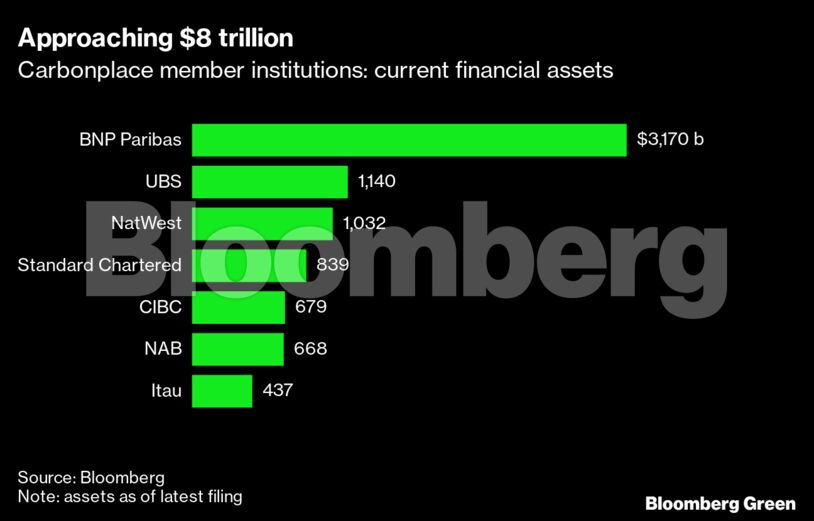

So I am interested to see an announcement this week from Carbonplace, a carbon credit settlement platform developed by seven financial institutions with nearly $8 trillion in total assets. Carbonplace has transferred verified credits from a carbon project developer to Visa, which purchased them, through Carbonplace’s own customer-ready banking platform. It is a glimpse of what bridging these worlds could look like.

According to Carbonplace executives, its platform uses a blockchain of the sort that carbon market web3 gurus promote, but does not require participants to maintain their own private registries of carbon credits, as many do today. Carbonplace satisfies its customer’s (Visa’s) needs without forcing it to perform its own counterparty due diligence, thanks to the capabilities of the platform’s bank members.

This transaction incorporates both of the KYC principles to solve multiple issues. The carbon registry knows its offsets; the blockchain records them; the settlement platform transacts them; the platform knows its customers. It is the sort of activity that hopefully joins the emerging world of carbon markets with the established world of bank transactions, to the mutual benefit of both.

What comes next? More transacting, hopefully, but also perhaps other instruments familiar to high finance. German-Singapore carbon offsets futures trading, anyone?

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS