Crude oil storage tanks are seen from above at the Cushing oil hub, appearing to run out of space to contain a historic supply glut that has hammered prices, in Cushing, Oklahoma, March 24, 2016. Picture taken March 24, 2016. REUTERS/Nick Oxford

LONDON, Jan 26 (Reuters) – An increase in oil output by producer nations cashing in on expensive crude has depleted the cushion of spare capacity that protects the market from sudden shocks and raised the risk of price spikes or even fuel shortages.

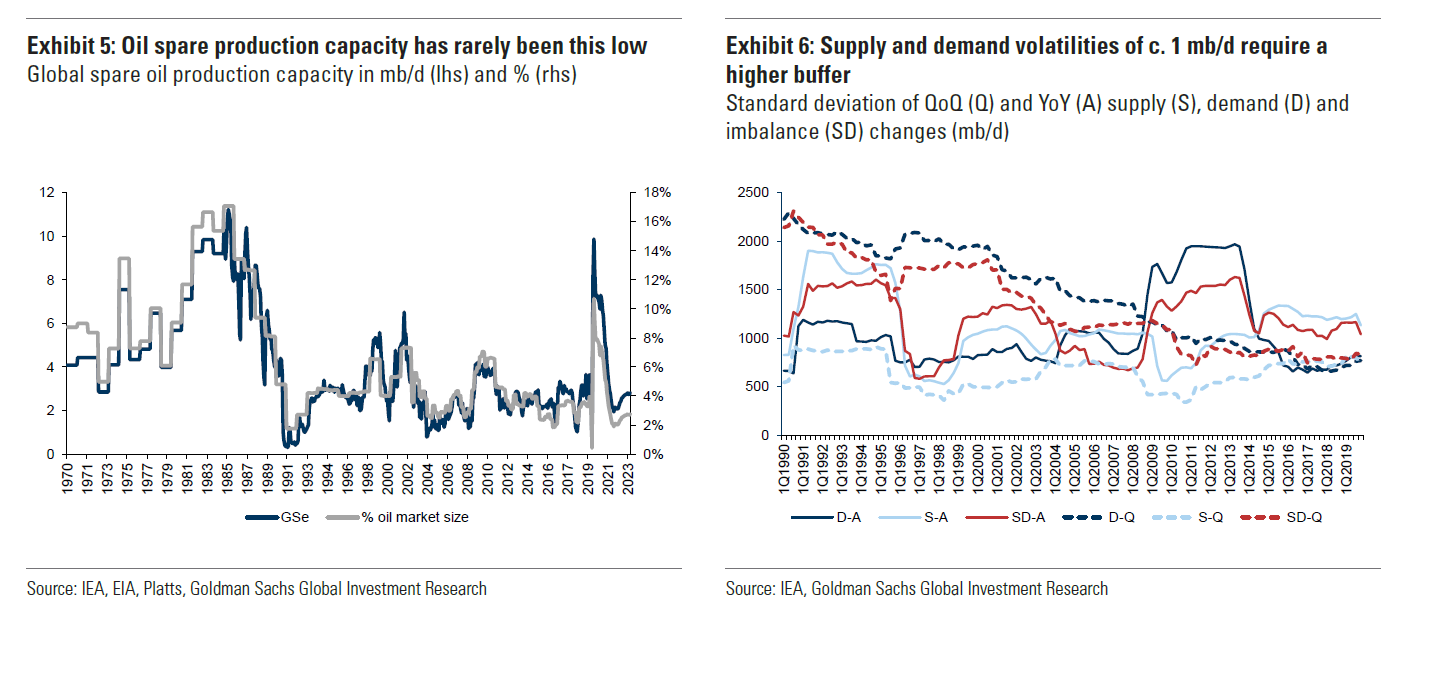

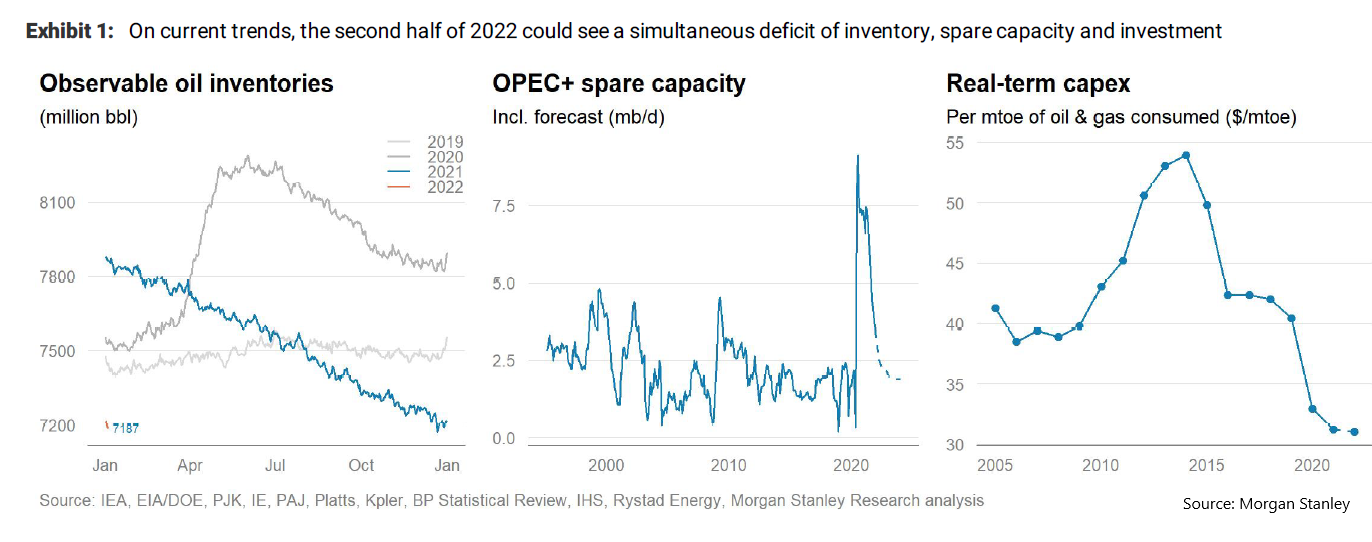

Some analysts have said that by the middle of the year unused capacity could be as depleted as in 2008 when international oil futures hit their all-time record above $147 a barrel.

Typically, the biggest producers, including Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, have capacity that they can draw on relatively quickly to add extra oil and calm price volatility should war or a natural disaster cause a sudden drop in supply.

Without that flexibility, consumers could be exposed to price shocks and fuel shortages.

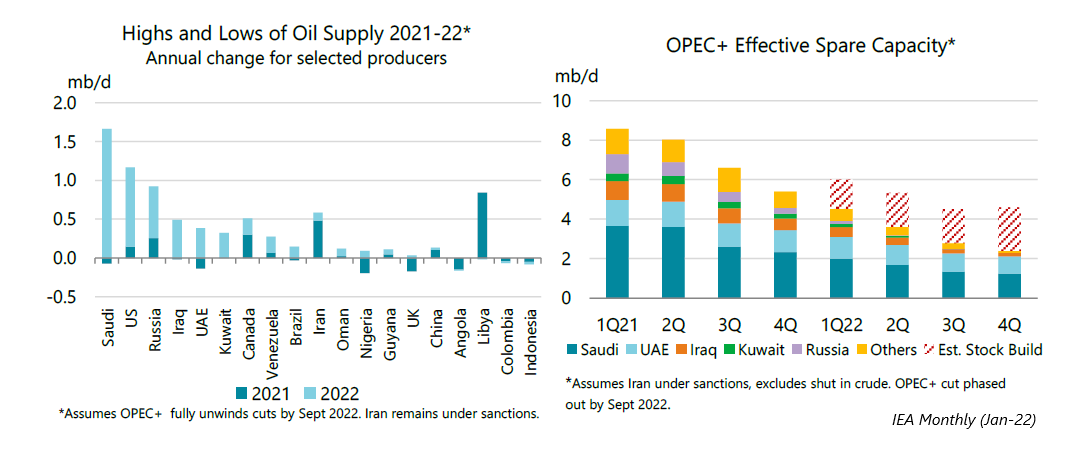

Last week, the International Energy Agency said spare capacity could fall by half to 2.6 million barrels per day (bpd) in the second half of the year.

“If demand continues to grow strongly or supply disappoints, the low level of stocks and shrinking spare capacity mean that oil markets could be in for another volatile year in 2022,” the IEA said.

The agency defines spare capacity as production that can be tapped within 90 days and sustained for an extended period, while the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) views it as the volume that can be brought on within 30 days and sustained for at least 90 days.

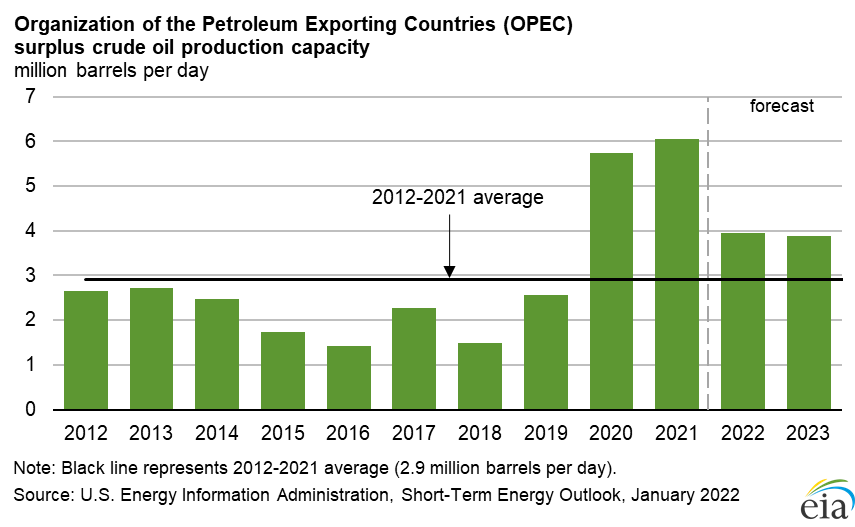

The EIA sees spare capacity averaging 3.9 million bpd in 2022, or 3.9% of global demand, above the 2012-2021 average, and says this “will be more than sufficient to meet additional demand even if consumption exceeds our expectation”.

Several analysts, however, say the spare capacity held by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries and allies (OPEC+) is much lower than the IEA and EIA figures, which they say underestimate the natural rate of decline in some of the producers’ oilfields

Goldman Sachs expects OPEC+ spare capacity to fall to 1.2 million bpd over the northern hemisphere summer, when the U.S. driving season boosts demand.

It sees levels this year at about 2% of the size of the oil market, similar to in 2008 when Brent oil hit a record $147 a barrel driven by boom in Chinese consumption.

It also sees oil inventories in the developed world falling to a 22-year low.

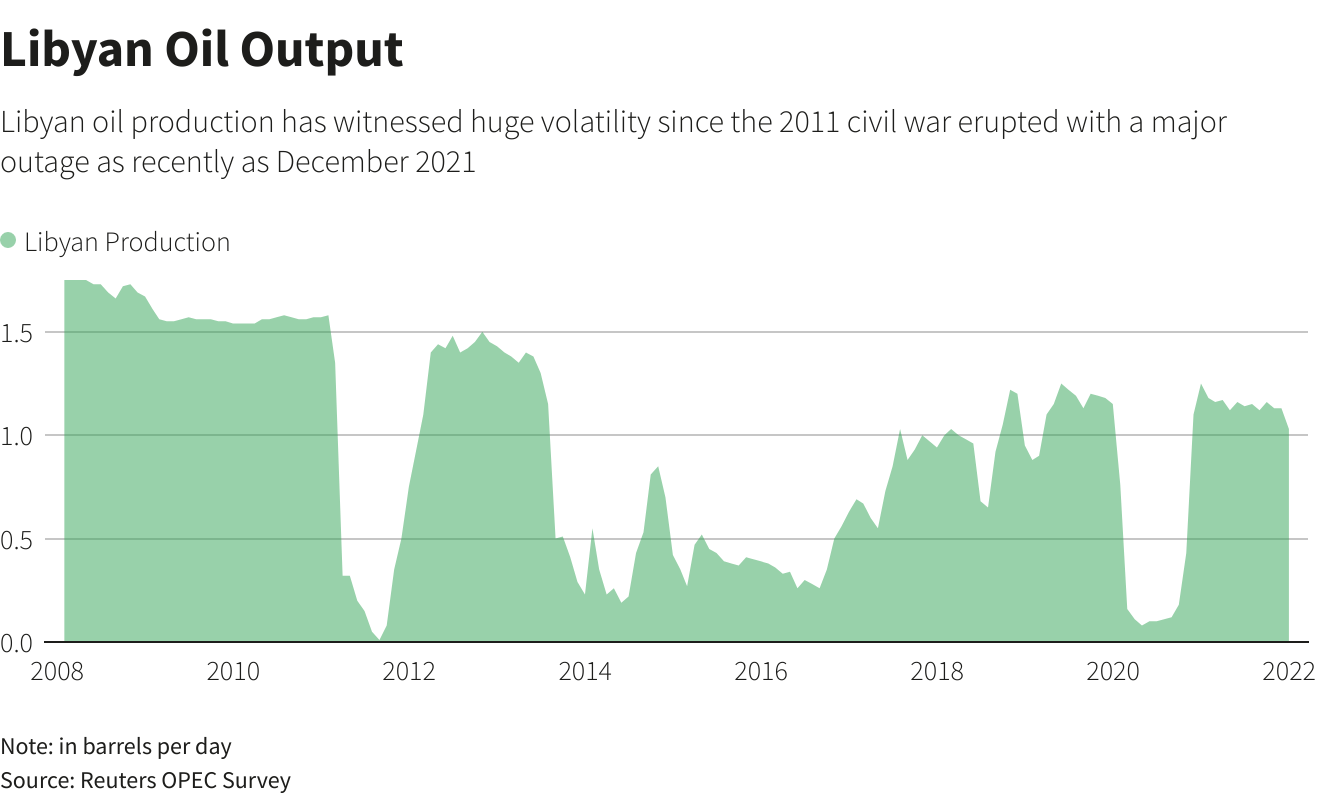

If those predictions are correct, a production shutdown in restive OPEC member Libya, for example, could be enough to use up all the spare capacity. In recent years, unrest in Libya has reduced its production by 1 million bpd for extended periods of time. For now, its output is about 1.2 million bpd, compared with a pre-2011 high of 1.6 million bpd.

Consultants Energy Aspects forecast spare capacity at 1.8% of global oil demand of about 100 million bpd by summer.

That level was last seen in April 2020, when OPEC+ members produced at full throttle as they disagreed how to tackle a price collapse caused by pandemic lockdowns that destroyed demand.

By June 2020, when OPEC+ had embarked on record supply cuts of 10 million bpd, spare capacity had increased to 11.4% of oil demand, Energy Aspects said, and Brent oil prices were trading at about $40 a barrel, less than half of today’s $89.

SHALE FACTOR

Spare capacity, is less volatile than prices, but has also had its ups and downs. In 2018, it plunged as the world braced for the reimposition of U.S. sanctions on OPEC member Iran, and in 2015-2016 when Saudi Arabia pursued a strategy of fighting for market share as the United States aggressively ramped up shale oil output.

The combined effect then was to soften prices and many shale producers went out of business.

“The new era of capital discipline among U.S. producers means that (unrestricted shale production) is no longer the case,” Energy Aspect’s Richard head of geopolitics Bronze said.

OPEC+, meanwhile, is unwinding the record supply cuts it implemented in 2020 as the world economy and demand recover from the impact of COVID-19.

Not all the producers can keep up with the rising production goals, especially West African producers struggling with limited investments and outages.

Last month, OPEC+ produced nearly 800,000 bpd below output targets, the IEA estimated.

Saudi Arabia is producing about 10 million bpd but has never produced more than 11 million bpd for a sustained period of many months, even though it says it has more capacity available.

Given the constraints, JP Morgan forecasts Brent oil prices will rise to $125 a barrel this year and $150 a barrel in 2023. read more

Morgan Stanley forecasts Brent prices at $100 by the third quarter, but says that is a level that will erode demand.

Any price spikes would be likely to be short term as the combination of demand destruction from higher prices and investment in bringing on new supplies would restore inventories and spare capacity.

Price spikes could also help to accelerate an ongoing shift away from fossil fuels as governments seeking to curb climate change regulate for the phasing out of combustion engine cars.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS