The recovery in production has put President Nicolas Maduro’s goal of 1 million barrels a day within reach. For a country with the world’s largest crude reserves, it’s not much. But the output boost adds another unpredictable element to an oil market roiled by signs of a Covid-19 resurgence, and Venezuelan oil minister Tareck El Aissami, one of Maduro’s chief lieutenants, is turning up the pressure to ensure the president’s production target is met.

“PDVSA has built new partnerships allowing it to increase production,” said Antero Alvarado, a managing partner at consulting firm Gas Energy Latin America. The cash-strapped company “is also paying service companies. All this amid high oil prices, sanctions and traditional partners unable to collect debts from PDVSA.”

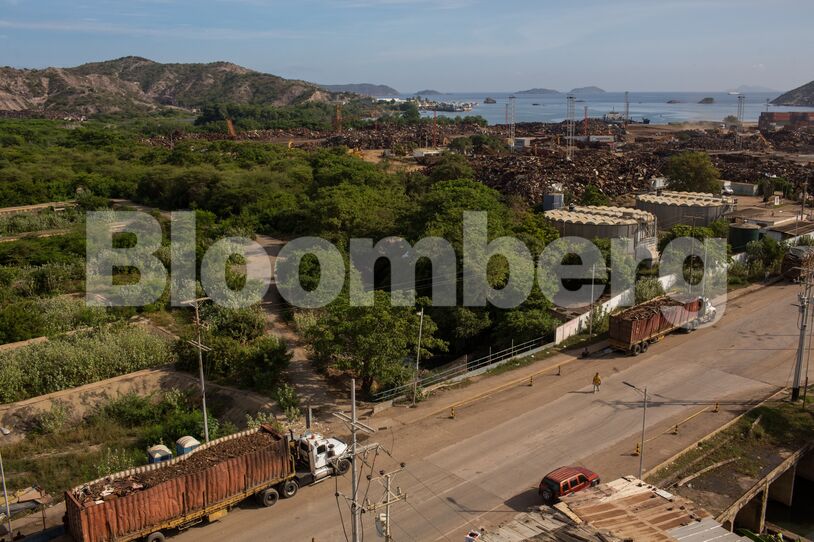

To the untrained eye, not much has changed in Venezuela’s Orinoco Belt. The region is still a shadow of the once-thriving hub that turned this South American country into a global energy giant. Vehicles that used to carry heavy drilling equipment to rig areas have largely disappeared. Foreign-owned warehouses are barren and deteriorating. Big dump trucks rumble down rutted roads, carrying scrap metal by the ton — dismantled pipelines to be sold abroad.

But in the short term, PDVSA’s gambit to ramp up production appears to be working, if slowly. Venezuela’s production of 908,000 barrels a day is close to that of Oman, a minor oil exporter among its peers in the Middle East. In the golden era of the 1990s, in comparison, Venezuela pumped more than triple that amount. Ship loadings of Venezuelan crude in November surpassed half a million barrels a day for the first time in a year. While it’s not clear where the oil will be sent, millions of barrels of the country’s crude have surreptitiously landed in China using tactics including ship-to-ship transfers, shell companies and silenced satellite signals.

READ: Thieves Ransack Venezuela’s Crumbling Oil Belt in Broad Daylight

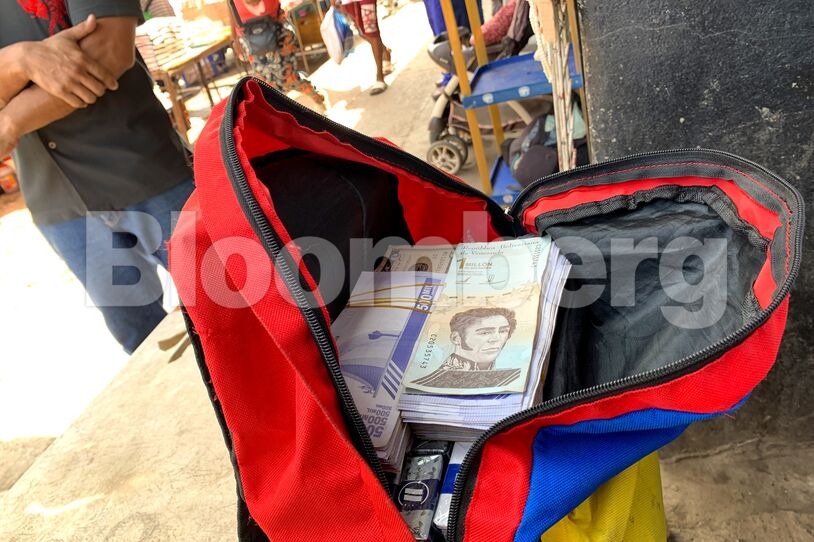

Many of the firms drilling for PDVSA work on an irregular basis given their lack of financing muscle and the state-owned producer’s late payments in cash, according to people familiar with the matter. The company remains hampered by years of mismanagement, scant investment from foreign partners and the weight of U.S. economic sanctions put in place under the Trump administration.

Still, the contractors have stayed on the ground. It’s an improvement over the previous two years, when PDVSA offered to pay in crude or fuel despite the complications that sanctions created for such transactions. PDVSA is concentrating on oil fields that are in relatively good shape, many of which were built and financed by foreign partners that have since halted work because of the sanctions on Maduro’s regime.

Oil minister El Aissami is turning up the pressure to ensure Maduro’s production goals are met. He’s a frequent visitor to PDVSA’s Jose industrial complex in eastern Venezuela, which processes raw crude into supply that’s ready for export. After years of decay, the complex has received a few recent cosmetic boosts: Resurfaced roads, refurbished tanks and the removal of weeds that had been engulfing some of the facilities.

Some observers question whether Venezuela can maintain the increase in oil output. Steady production of more than 750,000 barrels a day is “a challenge for PDVSA,” Alvarado said, with frequent fires and other mishaps threatening to curtail supply.

Regular supplies of Iranian condensate are also key. That light crude allows PDVSA to move the sludge-like petroleum that’s pumped out of the Orinoco Belt to mixing plants near the coast, where it can be upgraded to a more commercial grade and shipped to markets. Three cargo ships containing 4.6 million barrels of Iranian condensate have arrived since July in Venezuela. PDVSA hasn’t said whether more ships are coming, but according to Iran’s semi-official Tasnim news agency, Tehran has urged more cooperation between the two countries on petrochemicals and refining.

While Venezuela focuses on oil fields that are in fairly good condition, dozens of other fields remain shut. PDVSA may still cannibalize those, breaking apart pipes, engines and other equipment it can sell to finance its operations. As long as that occurs, the country’s reemergence as an oil superpower will remain a distant dream.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Trump’s Big Bill Shrinks America’s Energy Future – Cyran