Unlike the pandemic relief bills passed since last year, the infrastructure package is a five-year authorization bill with money spread through 2027. Not all of the money is mandatory, either — some discretionary programs will need Congress to continue to fund them year after year.

“This funding isn’t going to show up tomorrow. It will take a little time to stand these programs up, but we’re ecstatic and ready for it,” said Jimmy Wriston, secretary of the West Virginia Department of Transportation.

Some provisions of the bill will take even longer than five years. A $1.2 billion upgrade of the Washington subway system won’t be fully paid until 2030. A drawdown of the strategic petroleum reserve could take until 2031. And some port infrastructure funds don’t have to be spent until 2036.

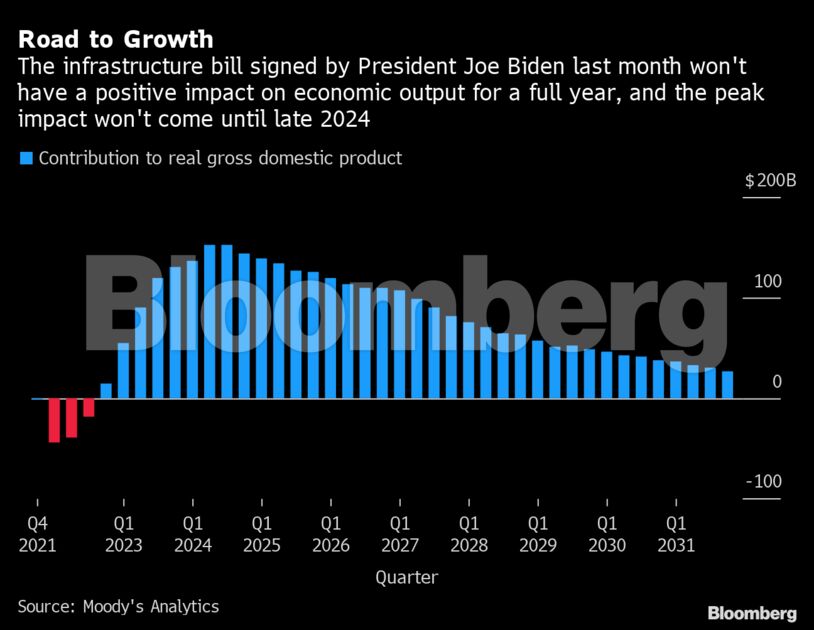

That timeline could blunt the law’s effectiveness as a campaign issue as Democrats struggle to keep control of Congress next year, and it won’t be an immediate panacea for the inflation and supply-chain problems that have dogged Biden’s poll numbers. He plans to visit Kansas City on Wednesday, his first trip to promote the public-works bill in a state that voted for former President Donald Trump.

Biden was pitching the new law to voters last week in one of five districts in the U.S. that voted for Barack Obama in 2012, Trump in 2016 and Biden in 2020.

“We know about our infrastructure problems — we’ve known for a long time. Now we’re finally doing something about it. No more talking. Time for action,” Biden said in Dakota County, Minnesota.

At last month’s signing ceremony for the bill, Biden said that it would be a solution to short-term constraints, saying it would “reduce supply chain bottlenecks, as we’re experiencing now.”

White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki tried to set more nuanced expectations.

“There are some components that we are going to see rather quickly and some that will take a little bit more time,” she said at Nov. 15 White House press briefing. “What the president feels this bill is going to help do is have an impact over the short, medium, and long term by putting more people back to work.”

The law is vast not just in size but in scope. It’s actually 15 different bills rolled into one — including the “Cyber Response and Recovery Act,” the “Repairing Existing Public Land by Adding Necessary Trees Act” and the “Wildland Fire Mitigation and Management Commission Act of 2021.”

The conventional surface transportation bill takes up about half of the final measure, but the rest of it will be administered by dozens of federal agencies, including the Energy Department, the Environmental Protection Agency and even the intelligence community.

One of the most visible infrastructure projects in the nation could take seven years to complete. The last three presidents have all used the 58-year-old Brent Spence Bridge, which links Ohio and Kentucky along the Interstate 75 Highway, as an emblem of the nation’s outdated infrastructure.

A local television reporter in Cincinnati asked Biden last month if he could guarantee that the infrastructure bill would fund a new bridge to ease congestion.

“The answer is yes,” Biden said.

But Kentucky Governor Andy Beshear said construction of the additional bridge over the Ohio River will depend on how much money the state can get from a federal grant application, which could eliminate the need for tolls. Plans for the bridge are now seven years old and would likely need to be updated. Construction would begin in 2023 at the earliest and take five years to complete.

Transportation officials say much of the money will be allocated by formula grants to states, who could apply some of it to pre-approved projects. Other programs — like installing electric vehicle charging stations or investing in smart cars that can prevent drunken driving — could take years to get started.

“Over the next 12 months you’ll begin to see some exciting news about how we’re bringing the plan to life,” said Deputy U.S. Transportation Secretary Polly Trottenberg.

“The good news is we know local transportation agencies have a lot of projects and are ready to start investing the money right away,” she said. “But I also want to be careful in setting expectations. This is a five year bill. Some of the projects are going to take some time.”

DOT will need to hire in order to administer all that money, as its annual budget swells from $90 billion to $140 billion.

“So obviously we are an agency that is going to grow,” Trottenberg said.

West Virginia is among large beneficiaries of the law, with $4.4 billion in expected federal spending. Its share of federal highway and bridge spending ranks seventh in the nation, even before including an allotment through the Appalachian Regional Commission.

The state’s Democratic Senator Joe Manchin wields a crucial vote for Biden’s legislative agenda, since the Senate is deadlocked at 50-50.

Each state has a four-year transportation plan, but they’re frequently amended and will likely need to be revised again to take into account the specific provisions of the infrastructure law.

“It didn’t come off of Mount Sinai with Moses. It’s a dynamic document,” Wriston said.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS