What’s touted as the world’s largest carbon capture and sequestration project is facing headwinds from farmers and environmentalists even as John Deere & Co. and New York financiers are investing in the $4.5 billion endeavor.

The Midwest Carbon Express is a privately financed, 2,000 mile-long pipeline network. It will collect carbon dioxide emissions at dozens of Midwest ethanol facilities and inject the emissions into underground porous rock in North Dakota, where project supporters say the emissions will be trapped forever.

The effort will safely store up to 10 million tons of carbon dioxide each year, slashing the region’s emissions from ethanol plants, according to Summit Agriculture Group, the project’s owner. Spread across five states, the project would create create as many as 17,000 temporary construction jobs and hundreds of permanent ones.

Such projects are necessary because the U.S. can’t immediately shut down all carbon-emitting facilities, including coal-fired power plants, and because there aren’t enough renewable energy sources are available to replace them, proponents said. Sequestration is needed to meet the Paris Agreement’s climate goals, they said.

“The science and the math are clear: We’re going to have to continue to burn fossils for the next 30 or 50 years, something like that, just to maintain reliability across the grid,” said Matt Fry, state and regional policy manager for the Great Plains Institute, an energy solutions organization that promotes carbon capture.

“So the question is, how do you do that in a carbon-neutral or carbon-negative manner?” Fry asked.

Opponents contend coal-fired power plants, regardless of sequestration’s potential, should be shut down because their emissions harm the environment. They also say it could fail to achieve the level of reductions claimed by project advocates and boost fossil-fuel use by using carbon dioxide to enhance the extraction process.

“We will fight these pipelines they same way we fought [the controversial Keystone XL] pipeline: using all-of-the-above organizing, including litigation,” Jane Kleeb, a spokeswoman for project opponent Bold Nebraska, said in an email.

10 Million Tons a Year

The project is one of two large-scale Midwest carbon capture and sequestration projects announced this year. The region is seen as a fecund one for such projects because of its concentration of ethanol and fertilizer-manufacturing sites emitting large amounts of carbon and suitable areas to sequester it.

The Summit project will install equipment at no fewer than 30 ethanol plants located in Iowa, Minnesota, Nebraska, North Dakota, and South Dakota that will capture nearly pure carbon dioxide emissions resulting from fermentation processes.

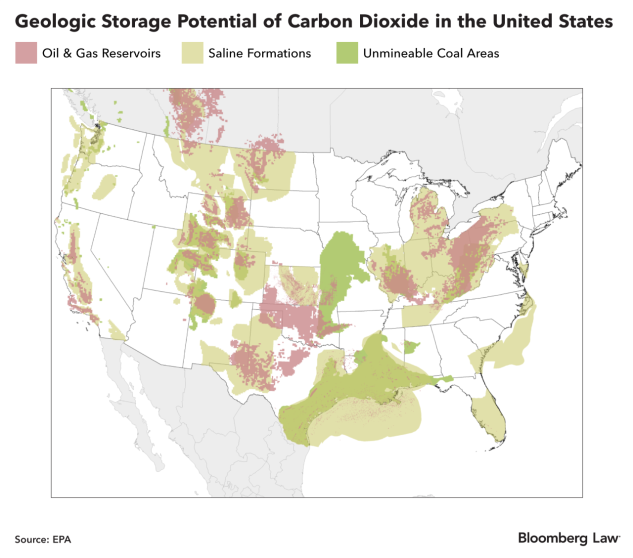

The gas will be compressed and sent in liquefied form by pipeline to injection wells in North Dakota. The carbon will then be injected into underground depleted oil and gas fields, deep coal seams, and saline formations, where project proponents say it will be trapped forever.

“Broadly speaking, we would expect to be sequestering at least 10 million tons of CO2 per year. When operational, we believe it will be the largest carbon capture and sequestration project operating globally,” said Justin Kirchhoff, president of Summit Ag Investors, a Summit Agricultural Group business unit.

Investors in the project include high net-worth individuals and venture capital firms that include Tiger Infrastructure Partners LP in addition to John Deere.

And Navigator CO2 Ventures LLC announced in October its Heartland Greenway project, a second Midwest carbon sequestration project. The Heartland Greenway will possess about 1,300 miles of pipeline across five Midwestern states and will initially capture carbon at about 20 industrial sites, mostly in Iowa.

That project, whose investors include BlackRock Inc. and is estimated to cost $3 billion to construct, aims to sequester carbon in downstate Illinois and forever remove carbon the emissions equivalent of taking 3.2 million vehicles off the road every year. Geophysical analyses of properties that might be used for the sequestration projects will be followed by the preparation and filing of permit applications. The projects could be sequestering carbon as early as 2024.

The Midwest Carbon Express will make money using Section 45Q of the federal tax code, which provides transferable tax credits to entities for either sequestering carbon emissions or using them for qualified industrial purposes. Projects can also qualify for loans and grants from the Department of Energy while investors who participate in carbon capture projects can improve their environmental, social, and governance ratings.

Sponsors of carbon capture and sequestration projects “get a higher ESG rating, and in turn this helps them get a lower cost of capital for borrowing,” said Mona Dajani, a Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP partner who leads the firm’s renewable energy practice and is an infrastructure deal maker.

Credits are incrementally increasing by the year and will reach a maximum of $50 for each metric ton sequestered and $35 for each metric ton used for a qualifying purpose. Other revenue possibilities include sharing in the revenue from sales of lower-carbon ethanol produced at the plants that meet certain states’ low-carbon fuel standards.

Litigation Exposure

Project opponents assert the Summit and Heartland Greenway projects will ruin valuable farmland and compel farmers to grow as much corn as they can to produce ethanol instead of adopting more sustainable practices.

They also cite the potential risk to polluting waterways and farmland if pipelines rupture and escaping emissions produce carbonic acid.

Further, carbon tax credits and trading markets aren’t climate solutions but ways to shift polluting emissions among entities to enrich private interests, the opponents assert. And companies capturing carbon could always use those emissions for industrial purposes, including boosting oil extraction from the ground—meaning more fossil fuel use.

Project opponents said challenging state and federal permit approvals could be part of a strategy to stop the pipeline.

“We have to fight through the regulatory process, we have to fight the use of public money, we need to get as many landowners against it as we can, we have to make the case that it’s not a public necessity,” Jessica Mazour, Sierra Club conservation program coordinator, said in an interview.

The Sierra Club has received funding from Bloomberg Philanthropies, the charitable organization founded by Michael Bloomberg. Bloomberg Law is operated by entities controlled by Michael Bloomberg.

Eminent Domain

The projects could rely on states’ use of eminent domain to site the pipeline if landowners refuse to grant access to their land voluntarily, some landowners worry.

“If this comes down to eminent domain there will be some big fights, I believe that firmly,” Beulah, North Dakota landowner and resident Kurt Swenson said in an interview.

Summit has asked Swenson to sign a lease agreement for his land. He hasn’t signed yet out of concern of some lease terms, though some of his neighbors have.

“We’re not opposed to the project, but we should have aligned interests with the project developer,” he said. “And while there is a large push for climate change regulations and carbon dioxide reductions around the world, that doesn’t mean you should be stealing someone’s property for private gain.”

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Trump’s Big Bill Shrinks America’s Energy Future – Cyran