The spread of the delta variant has held back millions of Americans from spending on services like restaurants and hotel rooms.

Supply chains are still creaking and Hurricane Ida, which caused havoc in petrochemicals hub Louisiana as well as roughly $20 billion of flooding damage in the Northeast, may have made them worse. And high inflation is stretching household budgets.

The Atlanta Federal Reserve’s real-time estimate of economic activity now predicts growth of just 1.3% in the quarter that ended in September. Two months ago it was forecasting 6%.

Economists surveyed by Bloomberg are more upbeat. Still, the consensus growth forecast for the third quarter has dropped sharply since August.

None of this means the U.S. rebound is heading into reverse, says Nathan Sheets, newly appointed chief economist for Citigroup Inc. “I think recession’s too strong,” he says. “But it’s certainly softer.”

Here are five indicators that illustrate and explain the gathering gloom.

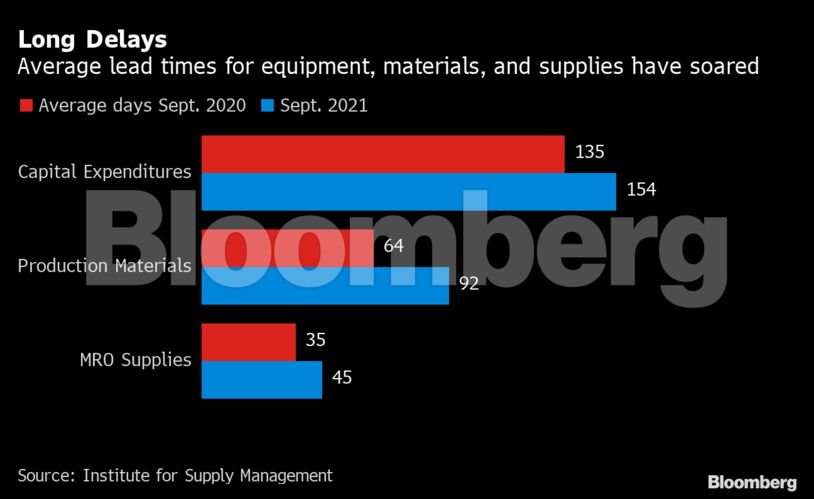

Delivery Delays

Many forecasters use the Purchasing Managers’ Index –- based on a survey of supply-chain managers — to gauge the state of manufacturing, which feeds into their growth estimates. One of its five components is supplier delivery times, and longer waits are typically seen as a sign of robust demand and a strong economy.

But in pandemic conditions, that may not tell the whole story. There have been unprecedented problems with shipping goods to the U.S., and transporting them once they’re here. In other words, the long waits may be as much a sign of supply weakness as strength in demand –- and confusing those two things may have led economists to be too optimistic about growth.

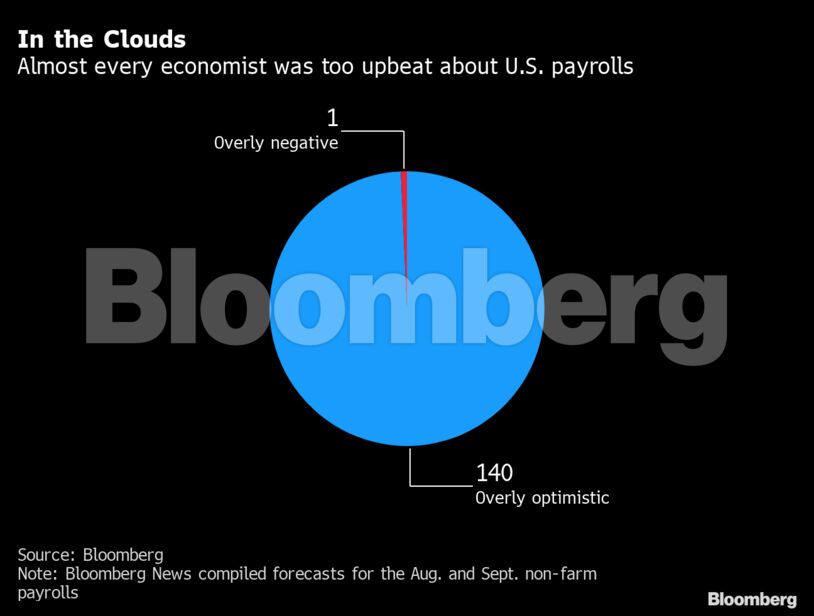

Missing Jobs

Economy watchers have also been flummoxed by the labor market. There are more than 10 million open positions – but the pace at which they’re being filled has slowed sharply. In the past two months, virtually every economist surveyed by Bloomberg over-estimated the number of new jobs.

The lowest-paid Americans are bearing the brunt of the slowdown. Among workers in the lowest quartile of earners, employment was down by 25.6% compared with pre-Covid levels as of mid-August, according to Harvard’s Opportunity Insights project. That’s the worst number since June 2020, a few months after the pandemic started.

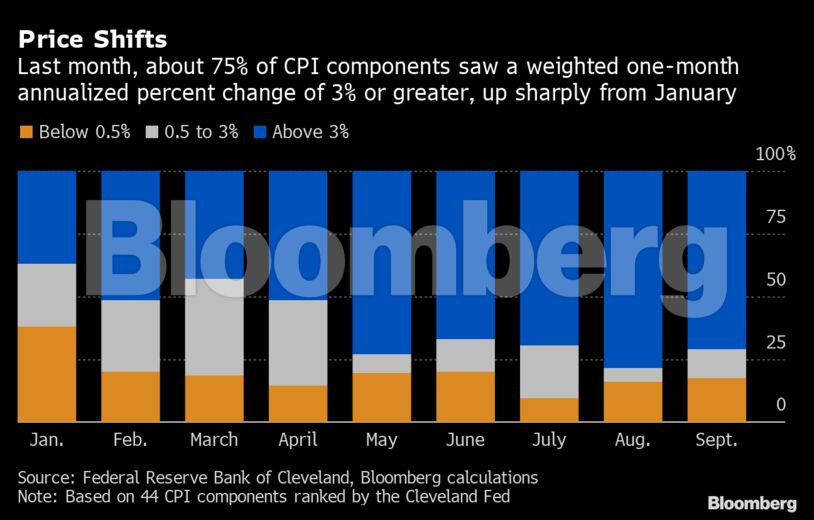

Inflation Bites

Inflation is throwing a wrench into the recovery too. The debate over whether pandemic price surges are transitory has yet to be settled – but they’re reaching ever-deeper into the economy, and crimping the spending power of households. Mark Zandi of Moody’s Analytics estimates the typical household has to pay $175 a month extra.

Energy and commodity costs are spiraling higher. Buying conditions for homes, vehicles and durable goods all deteriorated in August due to high prices, according to the University of Michigan’s latest consumer report. Auto purchases fell from an 18.5 million annual pace in April to just 12.2 million last month.

The first wave of pandemic inflation was confined to a relatively small group of goods and services. That’s no longer the case, according to the Cleveland Fed.

Its researchers found that in recent months, roughly three-quarters of the 44 main components of price baskets were growing at a pace above 3%. That compares with less than one-third of them at the start of this year.

Services Lag

The pandemic upended American spending habits. Households are buying more goods than ever before — a splurge that’s contributing to the strains on supply chains. But economists say a balanced recovery will require more spending on services too, and that’s happening more slowly.

Restaurants are one example. The spread of delta in the summer months halted the revival of dining out, which has settled at levels below what was normal before Covid hit.

Gloom Feeds Gloom

Business leaders and the general public are turning downbeat about the economy –- and those expectations can be self-fulfilling, if they mean that companies invest less and households are more cautious about spending.

The Michigan consumer survey found that only 44% of Americans expect their financial situation to improve, the lowest reading in seven years.

Sentiment among small-business owners deteriorated in September, with the number who expect better business conditions over the next six months falling to the lowest since December 2012. A CEO confidence measure compiled by Chief Executive magazine has also declined for three straight months –- to a level that means all of the gains earlier in 2021 are now gone.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Fossil Fuels Show Staying Power as EU Clean Energy Output Dips – Maguire