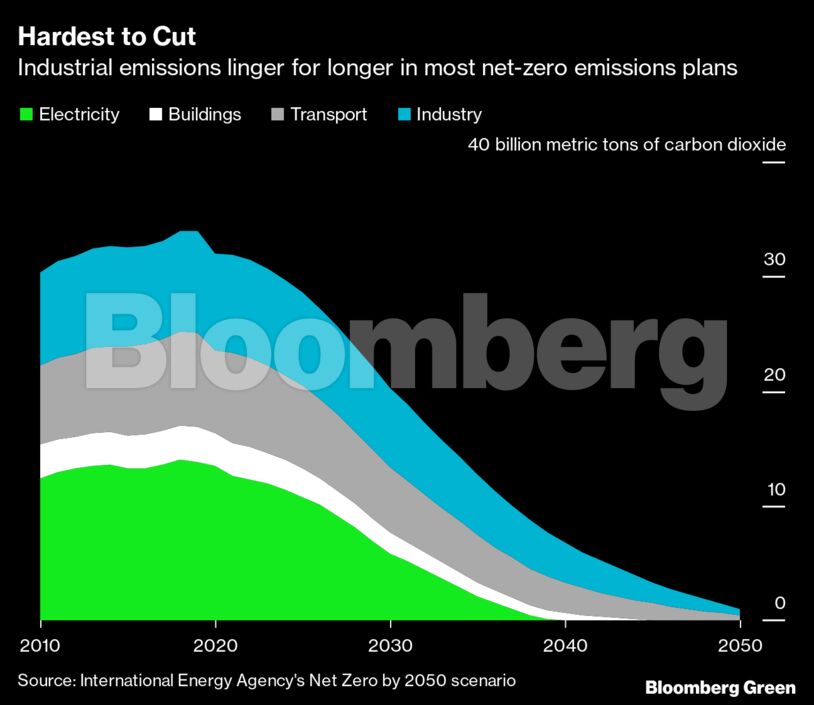

The commitments will target four sectors initially: aviation, shipping, steel and trucking. Technologies to cut pollution from them exists, such as sustainable jet fuel, ships running on methanol, steel made from green hydrogen and electric trucks. But those solutions often are a lot more expensive than fossil fuel-reliant routes, and the product supply isn’t always available at scale.

“These are the most difficult industry sectors for anybody dealing with the climate challenge,” Kerry said in an interview. “Not because it’s inherently impossible, but mostly because it hasn’t had a lot of focus.” At a meeting in Geneva last week, Kerry met chief executive officers of 30 companies that he hopes to convince to join the FMC. The State Department declined to share the full list.

New technologies follow a learning curve. As engineers build more solar panels or lithium-ion batteries, they learn how to make them better and cheaper. While government policies have helped some high-profile solutions like EVs ride that curve quickly, many of the most-polluting businesses haven’t received that kind of support.

Emerging technologies are forecast to account for 50% of the reductions in emissions in 2050, when the world should hit net zero to keep warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius relative to pre-industrial times. Increasing demand for greener alternatives will lower their price tag and help decarbonize the supply chains of the four segments cited by the coalition.

And large companies can make those commitments today without breaking the bank. For example, using green steel would add only about $180, or about 1%, to a car’s sticker price, according to the Energy Transitions Commission. Using a zero-carbon ship to carry a $60 pair of jeans would cost an extra 30 cents.

“There is a chicken-and-egg problem for products from hard-to-abate sectors. Supply or demand, what comes first?” said David Hostert, head of research for EMEA at BloombergNEF. “Purchase commitments give the demand signal that can go a fair way to help these industries scale.”

In Europe, many of these emissions-heavy industries face higher carbon bills after permit prices on the European Union’s emissions trading system doubled this year. That surge already acts as a stick forcing companies to decarbonize, Hostert said. Purchase commitments could be the carrot.

The initial pledges to the coalition also come from Indian companies Dalmia Cement Bharat Ltd. and Mahindra & Mahindra Ltd.; wind-power firm Orsted A/S; fertilizer maker Yara International ASA; utility Vattenfall AB; building technology provider Johnson Controls Inc.; and logistics company DHL Group. The details of those commitments won’t be announced until COP26 or the WEF meeting in Davos, Switzerland, next year.

“No single company can achieve net zero alone,” said Jan Jenisch, chief executive officer of Holcim. “Working together with like-minded companies, we can accelerate our economy’s transition.”

Later in 2022, FMC will expand its remit to cover another four polluting sectors: aluminum, cement, chemicals and direct air capture. Industry-led efforts will be critical for handling the actual work of developing clean alternatives to carbon-intensive materials like steel or cement, said David Victor, a professor of international relations at the University of California at San Diego who has been a lead author of United Nations climate reports.

Although COP26 is for countries to meet and hash out plans to cut emissions, private companies can play supportive roles. Many of the largest corporations earn revenue larger than the gross domestic products of some countries. Apple’s 2020 revenue, for instance, eclipsed Finland’s GDP for that year.

“Business was a critical component of the success of Paris,” said Kerry, who was U.S. Secretary of State in 2015 and played a key role in getting 195 countries to sign the agreement. Perhaps FMC-like coalitions, which are narrowly targeting an industrial sector or super-warming gas methane, could do the same for the Glasgow meeting.

Bill Gates led an effort similar to the FMC through his non-profit Breakthrough Energy. The Catalyst program created a $1 billion fund — including donations or investments from BlackRock Inc., Microsoft Corp., and General Motors Co. — meant to seed the building of plants to make clean jet fuel and green hydrogen. The fund will provide some initial money and expect the startup to raise 90% of the capital needed for the factory.

FMC isn’t directly stumping up cash. Though company announcements may add up to billions of dollars for green products, the commitments are voluntary. That’s not a new route in climate diplomacy. All the country-level commitments under the Paris agreement aren’t binding legally, and yet it’s been enough build global momentum toward reducing emissions.

Still, public monies likely will be needed. Companies that initially may have resisted the costly new approaches eventually will have few reasons not to embrace them as the technologies become cheaper or carbon prices rise, but state backing during that transition is critical, Victor said. “None of these major initiatives could happen without government support,” he said.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS