The cost of the fuel is already at record seasonal highs in most major markets and looks likely to rise further, threatening to dent the recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic.

The coming winter may give the world a painful lesson in just how pervasive and vital gas has become for the economy. Unaffordable prices could crimp households’ spending and erode their wages through inflation, giving central bankers some difficult policy choices.

Worse still, actual supply shortages could idle swathes of industry, or even trigger blackouts in developing countries, potentially causing social unrest.

“Energy lies at the base of an economy,” said Bruce Robertson, an analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. “High energy prices reverberate through the supply chain” and could dent the nascent recovery, he said.

Energy costs are rising around the world as the recovery in demand from the worst of the Covid-19 lockdowns collides with supply constraints. Oil has already undergone a long rally that started in late 2020 and ended at multi-year highs above $75 a barrel in July.

Gas began to rise in earnest at the start of summer in the northern hemisphere, when it became increasingly clear that there wasn’t enough supply in Europe to allow the usual refilling of storage sites depleted in winter. The continent’s largest supplier, Russia, has been limiting pipeline exports due for a number of reasons including high domestic demand, output disruptions and an agreement to transit less of the fuel through Ukraine.

“We’ve been running behind the storage delay all summer,” said Alfred Stern, chief executive officer of Austrian oil and gas producer OMV AG. Consumers in Europe are now at the mercy of the weather and the trajectory of prices “will now depend on how cold this winter is.”

In Europe, the price of gas has since surpassed oil, but the problem isn’t contained within the region. While the Russian supply constraints don’t directly affect consumers in Asia, they must still compete with Europe for seaborne shipments of liquefied natural gas, forcing them to pay higher prices to secure deliveries.

“High gas prices today are a problem for Europe,” Francesco Starace, the CEO of Italian utility Enel SpA, said in an interview on Bloomberg TV on Friday. “They might be a problem for Asia too.”

The LNG market is what connects Europe, Asia and the U.S., and high prices there feed through to the domestic American market by stimulating greater exports of the super-chilled fuel. Natural gas futures in New York have risen 80% this year to highest since 2018, although they are still far lower than in the other major global markets.

“The European market and the American market are in a similar place heading into the heating season,” said Nina Fahy, a natural gas analyst at Energy Aspects Ltd. in New York. “We could potentially have storage adequacy concerns if we have colder-than-normal weather, given how high LNG exports are expected to be.”

Damaged Industries

Around the world, the economic consequences of the natural gas rally are becoming evident.

Tereos SCA, the biggest sugar producer in France, warned last month that the price of the fuel is affecting sugar processing in Europe, increasing production costs “tremendously,” according to a copy of an email sent to clients and seen by Bloomberg News.

High energy prices are creating “inflationary pressure on every other cost” that will end up being passed on to customers, said Pascal Leroy, senior vice-president of core ingredients at Roquette Freres SAS, a food processing company based in northern France.

In China, the world’s largest gas importer, ceramic factories have been forced to reduce output due to high prices in Guangdong and Jiangxi provinces, according to local reports. Surging utility bills have “sabotaged” the business of Mughal Steels in Pakistan, according to Chief Operating Officer Shakeel Ahmad.

“We consume the gas first and get a high bill later,” he said. “How can I go back to a client saying that I need to add extra cost to the steel that I sold you?”

JPMorgan Chase & Co. said this week that its index of global manufacturing managers fell to a six month low in August, although it still indicated expansion.

Some poor countries, like Bangladesh, can’t afford to procure enough energy supplies to keep their economies buzzing. Some irrigation systems in the country may only be able to run at night because of potential power rationing, according to people surveyed by Bloomberg.

Current LNG prices in Asia are “absolutely not normal,” said Leonid Mikhelson, CEO of Russian LNG producer Novatek PJSC. “There may well be refusals” from customers that can’t afford it, he said.

U.S. manufacturers have yet to see a big hit from the rising cost of gas, because many energy-intensive industries like steel and petrochemicals have also seen the price at which they sell their products surge, said Fahy of Energy Aspects.

Economic Ripples

A crisis that’s largely playing out in heavy industry in Europe and Asia today could soon spread to the political and macroeconomic arenas.

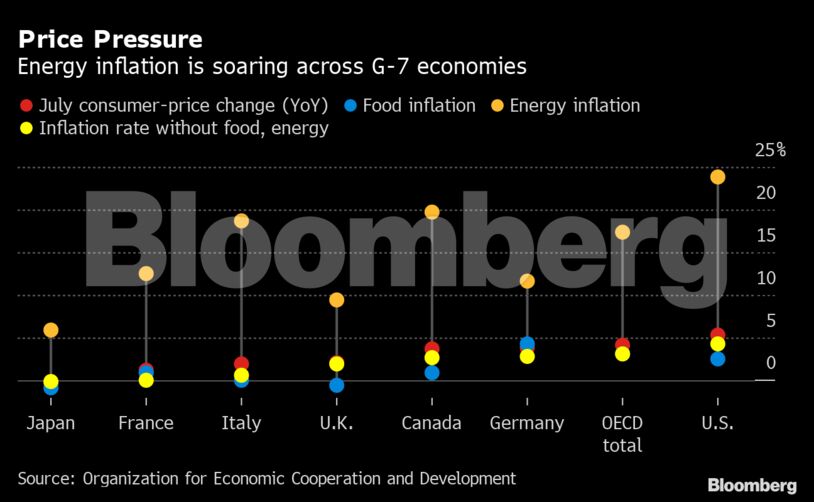

If households and businesses see their utility bills rising, they may seek to push up wages or the price of the goods they sell, compounding the inflationary pressure already resulting from strained supply chains.

The headline rate of inflation in the euro area has already surged to a decade-high of 3%. European Central Bank officials insist that this post-pandemic spike should prove temporary, but a lasting pickup would complicate their ability to keep supporting the economy through ultra-easy monetary policy.

“The likelihood that the producers pass on the costs is very high,” said Carsten Brzeski, an economist at ING Groep NV in Frankfurt. That means inflation may “not be that transitory.”

A lasting period of rising prices for the cost of essential goods can have social consequences.

“In many emerging market economies, even slight increases in retail fuel or energy prices can lead to economic hardship and public unrest,” Eurasia Group analysts said in a note dated Aug. 31.

In Pakistan, the government has come under fire for purchasing the nation’s priciest LNG shipments since they began importing the fuel in 2015. The cost of energy could become a “hot potato” in the upcoming German election, said Ole Hansen, head of commodity strategy at Saxo Bank A/S.

“Public opinion is not yet focused on” rising energy prices, said Julien Hoarau, head of Paris-based consultant Engie EnergyScan. “But at some point, public opinion will react and will start questioning: What is going on here?”

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS