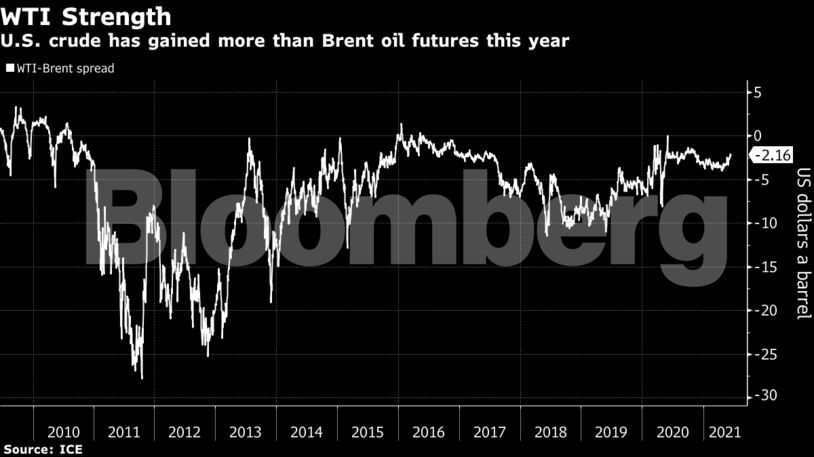

This dynamic is pushing U.S. crude prices higher. It’s even raising the possibility that for the first time in 5 years, West Texas Intermediate oil could get neck-to-neck with global benchmark Brent.

As little as 18 months ago, that would have been unthinkable, but the fact it’s even a peripheral view now underscores the transformation the oil market has seen during the pandemic. The move is already set to have ramifications on U.S. exports. With shale drillers not breaking their vows of capital discipline and the world’s largest economy leading the West’s reopening, U.S. refiners are clamoring to snap up more barrels domestically, rather than see them leave for export.

“It’s a function of U.S. demand accelerating out of the gate,” said Michael Tran, an analyst at RBC Capital Markets, who says that WTI has an outside shot at reaching parity to Brent, but is not his base case. “The market is realizing that WTI needs to price higher to choke off exports and incentivize imports, otherwise regional balances will become too tight by summer.”

Refineries across the U.S. are running at their highest levels since before the pandemic as demand comes back with most of the economy open again. Fuel-making plants in the Midwest that most rely on Cushing, are processing crude at the highest rate since September 2019, adding further support for WTI.

Capital discipline from the shale patch coupled with more domestic demand has done a lot to whittle down inventories in Cushing, Oklahoma, the delivery point for the Nymex WTI futures contract. Seasonal stocks at Cushing are at a three-year low.

The result is a growing backwardation in the U.S. oil futures market where oil for prompt delivery is more expensive than later-dated contracts. That’s prompting traders to sell their barrels now rather than hold them for later.

“This is a sure sign of US crude market tightness,” said Eugene Lindell, an analyst at consultant JBC Energy GmbH.

Because of the lower output, there’s more pipeline space available currently. That’s spurred some operators to discount their transport fees to drum up business. One example is Centurion Pipeline LP and Energy Transfer LP which are asking for under $1 a barrel to move supplies on their joint system this month from Cushing to Nederland, Texas on the Gulf Coast. With cheaper pipeline costs to the region, the WTI-Brent spread doesn’t need to be as wide to sustain crude exports

The relative enthusiasm for WTI is also showing up in where traders are deploying their money. Total open interest across all WTI contracts rose above that of all Brent futures months for the first time since 2018 last month. WTI open interest is up about 15% this year, while Brent is only up 1%.

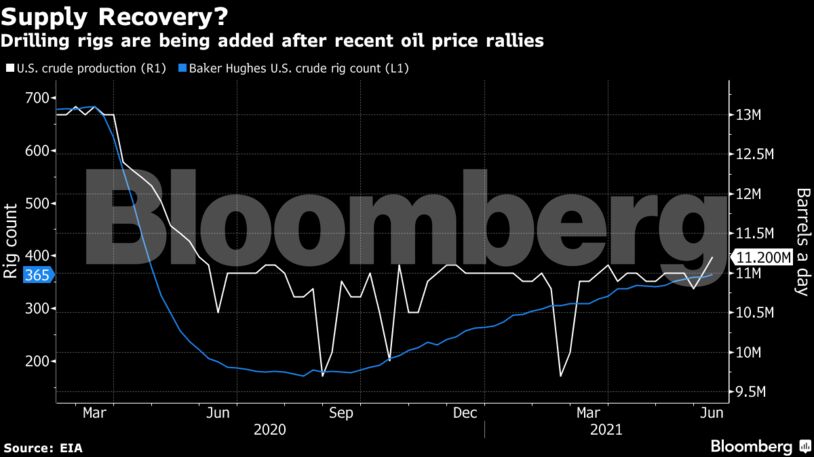

There are expectations that WTI could close its gap further with Brent, but the prospect of reaching parity may be limited. For one thing, the production slowdown across America’s shale patches is seen as temporary especially given the recent price rally where Nymex futures has risen nearly 50%.

Early signs of a production comeback might already be emerging. A weekly government report showed domestic output last week rose by 200,000 barrels a day to the highest level in over a year.

“U.S. oil production will be significantly higher by the end of this year, a good 400,000 barrels a day higher, and some more next year,” Ed Morse, global head of commodities research at Citigroup said by phone.

And while that could dent the spread in the long-term, Morse says the strong levels of U.S. demand right now mean the WTI-Brent spread could tighten for a little while more yet.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS