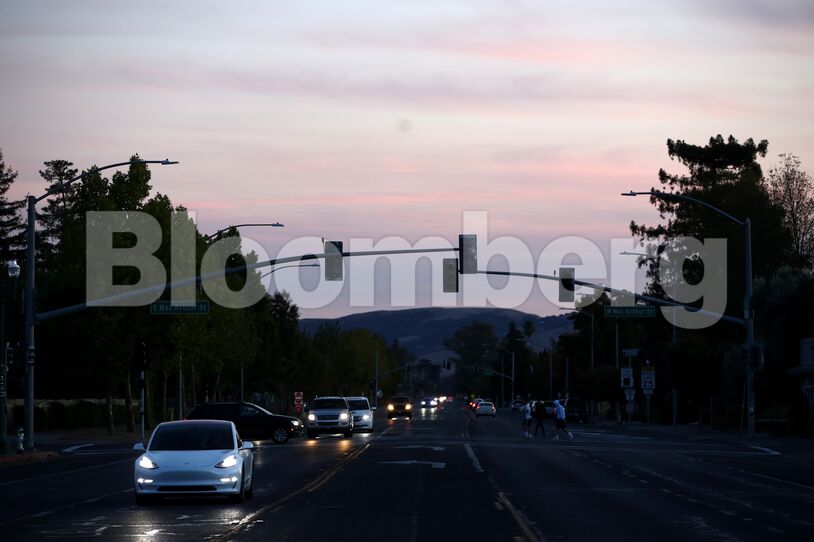

From New Mexico to Washington, power grids are being strained by forces years in the making — some of them fueled by climate change, others by the fight against it. If a heat wave strikes the whole region at once, the rolling outages that darkened Southern California and Silicon Valley last August will have been previews, not flukes.

“It’s really the same case in different parts of the West,” said Elliot Mainzer, chief executive officer of the California Independent System Operator, which runs most of the state’s grid. “It’s revealed competition for scarce resources that we haven’t seen for some time.”

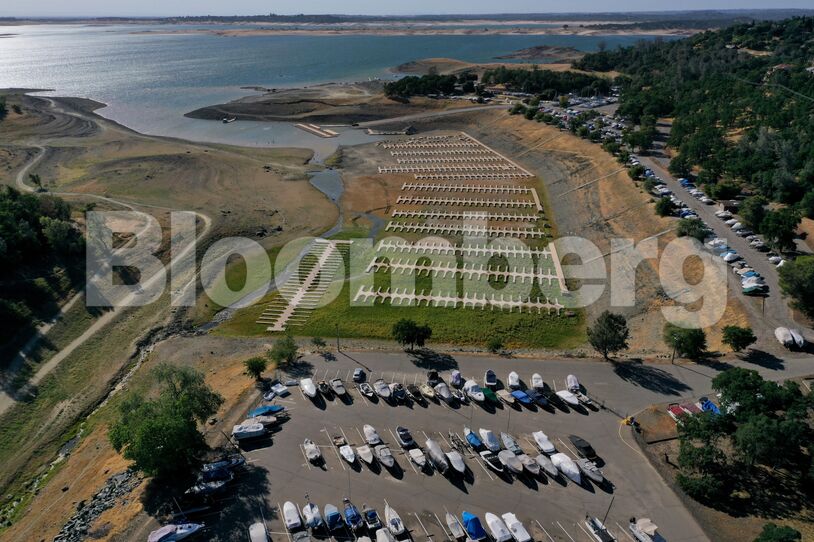

The specter of blackouts highlights a paradox of the clean-energy transition: Extreme weather fueled by climate change is exposing cracks in society’s move away from fossil fuels, even as that shift is supposed to rein in the worst of global warming. States shuttering coal and gas-fired power plants simply aren’t replacing them fast enough to keep pace with the vagaries of an unstable climate, and the region’s existing power infrastructure is woefully vulnerable to wildfires (which threaten transmission lines), drought (which saps once-abundant hydropower resources) and heat waves (which play havoc with demand).

On Wednesday, California’s grid managers warned that while they’re better positioned than last summer, the risk of power shortages during extreme heat remains a clear possibility.

For many, California’s power crisis in 2020 was the first indication of how serious the regional power shortfall had become. While the blackouts highlighted the state’s reliance on solar power — a resource that ebbs in the evening just as demand picks up — an equally significant problem was California’s dependence on imported electricity. Utilities routinely source power supplies from out of state, drawing electricity across high-voltage transmission lines to wherever it’s needed. But last summer, neighboring states coping with the same heat wave as California were straining to keep their own lights on, and imports were hard to come by.

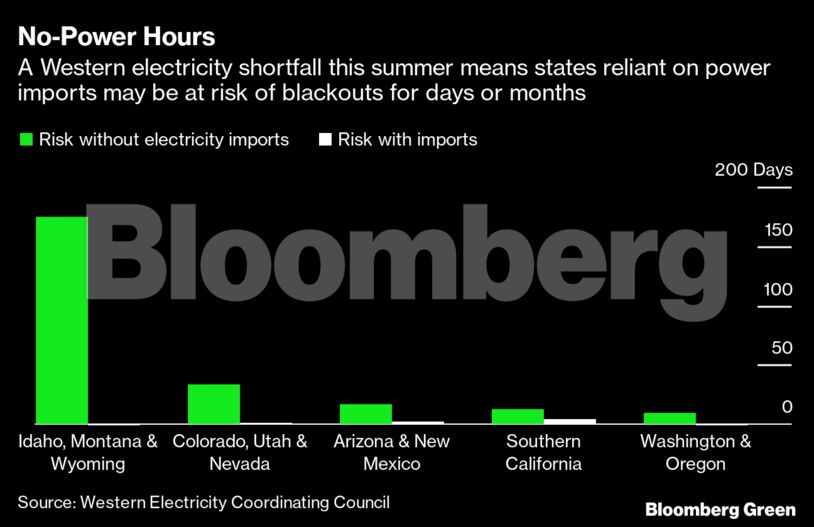

This year, that dynamic is playing out on a larger scale. Across the West, states have grown dependent on importing power from one another. That works fine in temperate weather, when electricity demand is relatively low. But it’s a problem when a widespread heatwave blankets the entire region. The Western Electricity Coordinating Council, which oversees electricity grids throughout the western U.S. and Canada, estimates that without imports, Nevada, Utah and Colorado could be short of power during hundreds of hours this year, or the equivalent of 34 days. Arizona and New Mexico could be short for enough hours to total 17 days, according to a report by the organization that looked at worst-case scenarios to help states develop plans to head off potential outages.

“It’s no longer necessarily a California problem or a Phoenix problem,” said Jordan White, vice president of strategic engagement for the group, known as WECC. “Everyone is chasing the same number of megawatts.”

While blackouts aren’t a guarantee in any region, traders are already betting on supply shortages and sending power prices soaring throughout the West. At the heavily traded Palo Verde hub in Arizona, prices have nearly quadrupled since last summer’s outages, while the Pacific Northwest’s Mid-Columbia hub has tripled.

“We are already seeing record-breaking prices across the West, some of which can be attributed to a fear factor being priced in,” said JP McMahon, a market associate for Wood Mackenzie. “Last year was a bit of a wake-up call.”

The reasons behind the shortfall are two-fold: Climate change is making it harder to forecast demand for electricity while the shift to clean energy is straining power supplies.

Where utilities and grid managers were once able to rely on predictable consumption patterns season to season — more air conditioner use in August, less in October — they’re now reckoning with record-hot summers and historic winter storms that cause great, unexpected surges in demand.

“It’s becoming challenging to take out the crystal ball to know with any level of certainty how hot it it’s going to be,” White said.

At the same time, older coal and gas plants capable of providing power 24 hours a day are being pushed out by climate change regulations and their own dwindling profitability. In the West, power generation from such plants slipped 6% from 2010 through 2018, according to WECC. While wind and solar capacity have more than tripled in the region, the output from those resources varies by the hour, making them harder to rely on during an unexpected demand crunch. Massive batteries can help make up the difference, but their installation is just beginning.

It’s a global phenomenon. Sweden this summer is bracing for power outages and curbing electricity exports after nuclear retirements have left the country with too little spare capacity to balance big swings in demand. In China last winter, even a surplus of coal plants couldn’t keep the lights on during a severe cold blast.

At this point, no subregion in WECC’s coverage area generates enough electricity to meet its own needs during periods of high demand; they all rely on imports to avoid outages.

In the aftermath of the California crisis, utilities have been signing up contracts for more emergency power supplies and are trying to make sure they aren’t relying on the same suppliers as everyone else. Some entities, including the Imperial Irrigation District of Southern California are working to curb their reliance on imports. But it’s not clear that all utilities in the highest-risk areas plan to do much differently.

The situation is, if not dire, getting close. Temperatures in the West are expected to be above average through the summer, with the worst heat slamming the Southwest. More than 84% of land in the 11 Western states is gripped by drought.

Following last summer’s outages, California is among the best positioned going into summer. The state is plugging roughly 1,500 megawatts of batteries into the grid, has postponed the retirement of several aging gas plants and raised the price cap on power trades to incentivize imports if outside supplies are necessary and available.

Even if imports are readily available for those that need them, there’s no guarantee that transmission lines will be able to carry those electrons where they need to go. Extreme weather can take out the high-voltage conduits that stitch the Western states together, and wildfires are notorious for knocking out transmission lines. Although it received little attention at the time, a major transmission line in the Pacific Northwest that suffered damage in a storm last spring limited power flows into California throughout the summer energy crisis.

Energy consultant Mike Florio, who used to sit on the board of California’s grid operator, said other states can learn from the West’s dilemma. They should keep a variety of resources as they decarbonize, learning how to balance the daily rhythms of solar and wind, and not move too quickly to shutter old gas-burning plants that can provide power in a pinch.

“We forget that we’re still learning a lot about how to run a system like this,” Florio said. “We probably want to keep our existing gas capacity, at least in reserve. It may be used less, but something that’s already built is cheap insurance.”

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Where the Fight Against Energy Subsidies Stands – Alex Epstein