If the president sticks to his guns, it could mark another milestone in the great policy rethink that got under way after the 2008 financial crisis.

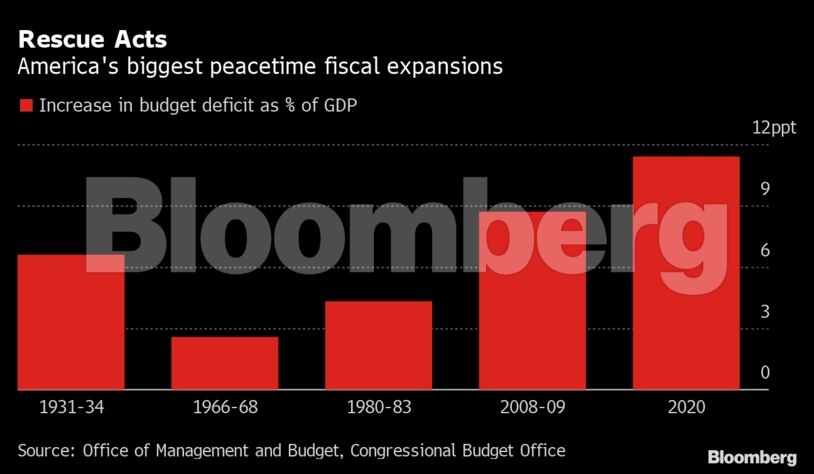

Biden’s $1.9 trillion aid plan would be the second-largest injection of federal cash in U.S. history. Only last year’s Cares Act was bigger — but that came at the start of the pandemic, when the deepest recession in decades lay directly ahead.

The next round of fiscal support, by contrast, will flow into an economy that’s already bounced much of the way back.

Millions of Americans, especially among low-income groups, are still suffering the full effects of the slump, and that’s why the government says another round of spending is vital. But aggregate numbers show that production of goods and services isn’t too far short of pre-pandemic output — thanks in part to households still flush from the last round of checks.

Vaccines may soon make it easier for Americans to spend all that cash. When they do, some form of inflation won’t be far behind, the skeptics say.

It’s a prospect that, not long ago, would have set off alarm bells all over.

For decades, the managers of the U.S. economy had a cautionary bias. Central bankers worried that prices might spike at any time. Budget officials fretted that deficits would get out of hand, trigger the bond vigilantes and send interest rates soaring. Both stood permanently on guard, ready to ward off such threats with tighter policy.

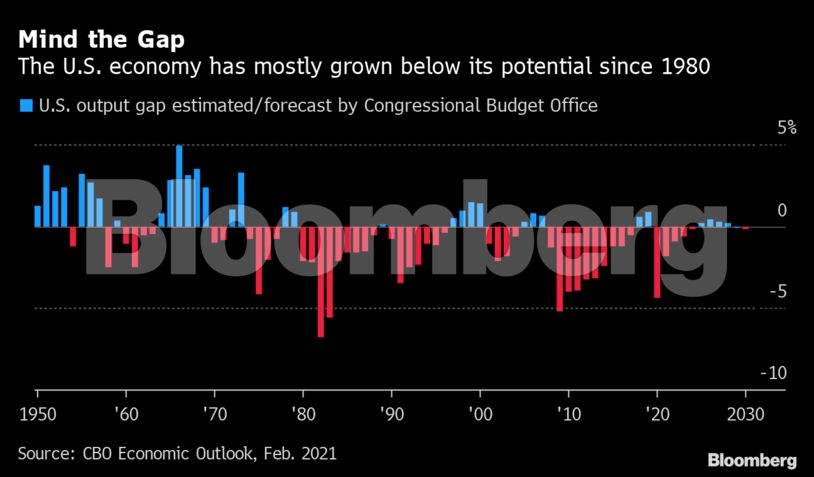

The result was an economy that expanded at below its potential growth rate in three-quarters of the years since 1980, according to the Congressional Budget Office. It grew steadily more unequal over that period too.

Since the financial crisis and the lackluster recovery that followed it, policy makers and economists have slowly come round to a different view. In effect, they’ve decided that it makes more sense to fight today’s problems with all the firepower they have, instead of trying to pre-empt tomorrow’s.

“There were a lot of people who cried wolf over the aggressive stimulus back in 2009,” even though it now looks timid with hindsight, said Jan Hatzius, chief economist at Goldman Sachs. “There was a lot of worrying about much higher inflation, and maybe a run on the currency, and a number of fairly alarmist scenarios — none of which played out.”

That’s one reason U.S. leaders were ready to “really go all out” in the pandemic, said Hatzius, who thinks the experiment has been a success and sees no reason for Biden to hit the brakes just yet. “I do think there are fiscal limits, but I don’t think we’re that close to those fiscal limits,” he said. “We have quite a lot of room to grow.”

By some measures, the U.S. economy is far from completing its virus recovery.

Almost 10 million fewer Americans were working last month than in February 2020. With unemployment that high, an administration committed to fighting inequality is unlikely to withdraw budget support anytime soon, according to Morgan Stanley.

‘High-Pressure Economy’

The Biden administration and the Federal Reserve now share the goal of a “high-pressure economy” that pulls low-income workers back into employment, and won’t take their foot off the gas till they get there, the bank’s economists wrote last week. They contrasted that approach with the one taken a decade ago, when fiscal tightening began with a jobless rate still close to 10%.

But while employment lags, production of goods and services has climbed back much closer to its pre-virus peak. Hatzius and the Morgan Stanley analysts are among those who expect output to reach that level by June -– and then power past it.

Household savings surged in 2020 as expanded benefits replaced lost earnings for millions of Americans while lockdowns left consumers short of spending options.

All of that makes for a combustible mix into which to throw another $1.9 trillion of stimulus, according to the overheating camp. Some worry that people who retained their jobs will get cash transfers they don’t really need, and plough the money into financial markets — contributing to bubbles like the one in GameStop Corp. shares.

Others cite a measure known as the output gap, the difference between what the economy is actually producing and the maximum it could sustainably manage. The CBO estimates a shortfall of some $700 billion through 2023.

Biden is proposing to spend two to three times the amount needed to close that gap, according to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. It said the results could include higher inflation and an economy hooked on stimulus.

Perhaps more surprisingly, Larry Summers -– a top official in the last two Democratic administrations and a longtime advocate of more active fiscal policy –- weighed in with a similar warning. Summers, who’s also a paid Bloomberg contributor, said the extra spending combined with a successful vaccine rollout could result in “an economy that is literally on fire.”

Output gaps are one of those economic concepts, like full employment, that essentially involve guesswork. They’re based on projecting the economy’s potential, which nobody really knows until it’s put to the test.

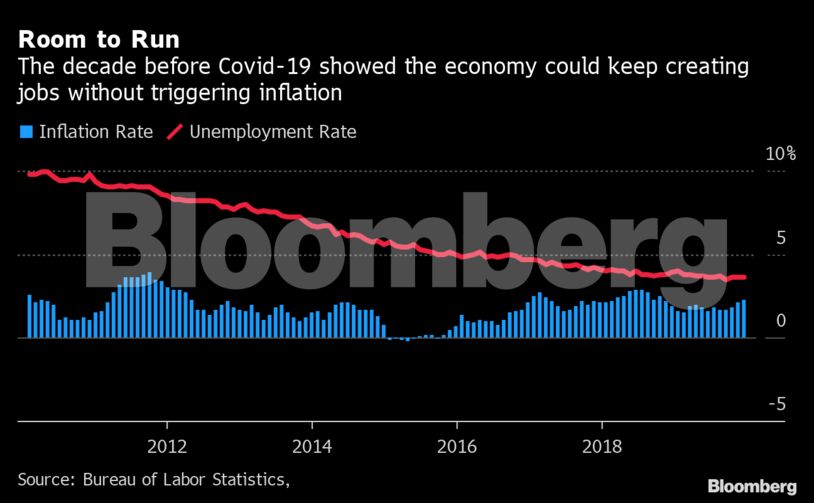

That point was repeatedly driven home in the years before the pandemic. Policy makers were surprised when unemployment kept falling without triggering inflation. Many economists said Donald Trump’s 2017 tax cuts, an unorthodox effort to juice an already growing economy with fiscal stimulus, would drive interest rates and inflation higher, but they didn’t.

Administration officials lined up last week to dismiss the idea that their bill could push the economy past some notional speed limit, and explain that what they’re trying to provide is more relief than stimulus.

“This package was built from the ground up,” by calculating the needs of workers, families, schools and health services, said Heather Boushey of the White House Council of Economic Advisers. “There is deep unused capacity in this economy,” said another council member, Jared Bernstein.

Ambitious Plans

The debate about overheating probably isn’t going away, because the virus package is just the start of Biden’s spending plans. He’s also pledged $2 trillion for clean energy, and almost $1.5 trillion for manufacturing and childcare. Those investments, unlike the transfer payments in the virus package, should expand the economy’s productive capacity — addressing one of the concerns raised by Summers.

But Biden’s Democrats hold the narrowest of Senate majorities, which could put his post-Covid-19 agenda at risk if the economy comes roaring back and enthusiasm for big-ticket spending wanes.

That makes it good politics as well as good economics to pass the biggest relief package that’s possible right now, according to the high-pressure camp.

“You don’t get an endless number of opportunities to do major bills,” said J.W. Mason, an assistant professor of economics at City University in New York.

Pumping up demand with government spending will force business into labor-saving innovation and deliver the biggest wage gains for workers at the bottom of the income distribution, Mason said. “If you care about inequality, you really want to run the economy hot. At least for a while.”

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

Trump Is Scaring Republicans Away From Saving the Planet