By Jonathan Tirone and Brian Parkin

Angela Merkel’s district on the Baltic coast was the site of the last major Soviet military project in communist East Germany and is now at the center of a deepening rift between Cold War allies.

Once a critical linchpin in the Soviet Union’s power network, the low-lying beachhead near the Polish border has become known as a getaway for Germans, who flock to the island of Ruegen to bike along sandy dunes and dip into its chilly sea.

Then came the Nord Stream 2 pipeline.

The European Union’s largest infrastructure project was supposed to give one of Germany’s poorer regions a path to the modern economy. But geopolitics intervened, with U.S. Congress passing a law that sanctions German companies involved in the Russian gas link. That transatlantic wedge is now threatening to splinter, with potentially costly outcomes to businesses.

No less than “democracy in Europe” and the EU’s “image of U.S. companies” are on the line, a German industrial group warned House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi last week in a letter. “The burden on the transatlantic partnership would be immense right at the beginning of Joe Biden’s term.”

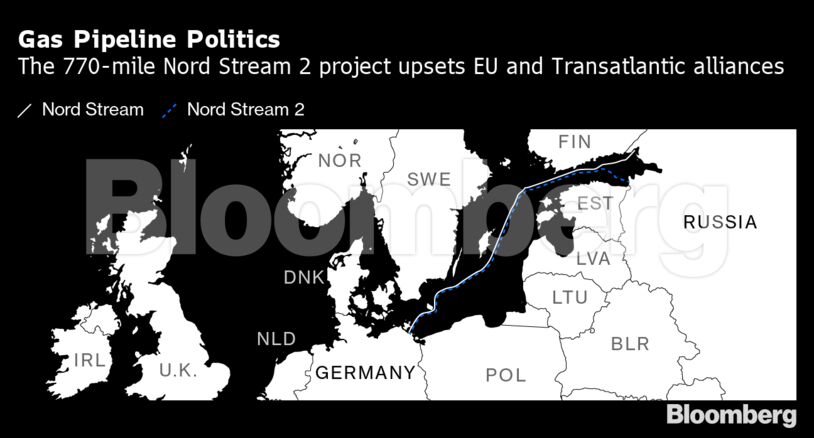

With broad-based opposition to the 1,239-kilometer (770-mile) pipeline in the U.S., German hopes that the president-elect will reverse sanctions may be misplaced. The friction is contributing to an array of issues fraying ties between Germany and the U.S., pushing Europe to chart its own course.

The fallout of the feud is hitting home in Sassnitz, site of Mukran Port — dubbed a “friendship bridge” to the Soviet Union by East Germany’s communist regime. The harbour on Ruegen is the key staging ground for the completion of pipeline, led by Russian gas giant Gazprom. It makes landfall nearby at Lubmin on the mainland, where it’s supposed to flow into the European gas grid.

“We’ve done nothing wrong,” said Frank Kracht, the mayor of Sassnitz, the biggest shareholder in Mukran, where workers and ships have been idled for months.

The question over whether Nord Stream is completed has focused the attention of investors from Europe’s industrial heartlands to the shale fields of Texas. For Germany, it offers critical energy security as the country phases out nuclear and coal power at the same time. For the U.S., there’s the risk of Russia gaining leverage over a key ally and the potential loss of a market for American liquefied natural gas.

Merkel has remained true to the controversial project, even as relations with Russia deteriorate. Germany said Monday it’s coordinating a response to U.S. sanctions with other EU nations, as well as the companies involved in the project.

“People in Mukran who lived under Soviet authoritarianism are completely surprised by the threats that are now coming from the U.S.,” said Wolfgang Klietz, the author of a book about the port. “But the threat of sanctions won’t stop the project. They’re seen as inappropriate.”

After U.S. sanctions forced western European workers to retreat, Russian vessels have been plying the waters in and around Mukran for months, awaiting orders to install the last remaining sections of pipe. A specialized vessel, the Akademik Cherskiy, killed time by meandering the world’s oceans, including rounding the Horn of Africa. It finally arrived in May.

Jutting into an area of the Baltic shared by Denmark, Poland and Sweden, the German base always had strategic value. One of Mukran’s special features is the broad-gauge railroad tracks still preferred by Russia. The world’s biggest train ferries — massive ships built to haul railroad boxcars — ran between Mukran and the Lithuanian port of Klaipedia.

During the last years of the Cold War, the German landing was a waystation for Soviet troops and military equipment, including nuclear weapons. The current dispute has echoes of those past tensions.

While Germany and the U.S. have had high-level policy differences in the past — most notably over the use of force in places like Iraq and Libya — this is the first time that disagreement has led to direct sanctions threats against installations in an allied country.

American policy makers have historically opposed European projects that lock-in economic ties to Russia, arguing that payments flowing toward the Kremlin destabilize military alliances. Donald Trump had repeatedly suggested European treachery at play in choosing Russian gas rather than LNG from an ally.

While Washington, former Soviet bloc countries and even some of Germany’s European allies say Nord Stream 2 will give Russia too much leverage, the country insists the pipeline is critical and have protested U.S. threats of “crushing legal and economic sanctions” against the Baltic Sea port.

Even with the political wrangling, the project shows how deeply integrated the economies of Europe and the U.S are. Austria’s Voestalpine AG manufactured the steel for the pipe with the help of its sponge ironwork in Texas — built in Corpus Christi next to Cheniere Energy, America’s biggest LNG exporter.

But U.S. opposition is likely to remain under Biden. “There’s American cross-aisle agreement” against Nord Stream, Ursula von der Leyen, European Commission president and Merkel’s former defense minister, told Germany’s Die Zeit newspaper earlier this month.

Biden has cautioned against the project in the past. At the Munich Security Conference in 2015, he said the U.S. needs to “ensure that no country — not Russia or any other nation — can use energy as weapon of coercion.”

Amid the stalemate, activity at the Sans Vitesse, a vessel used to house gas and pipeline workers in Mukran, has fallen silent, and locals are feeling their chances of upgrading their economy slipping away.

“With just the threat of sanctions, there can be little doubt that multinational companies with units in the U.S are thinking twice about investments in this region — stuck as we are in the middle of a global political standoff,” said Sassnitz Mayor Kracht.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS