By Julian Lee

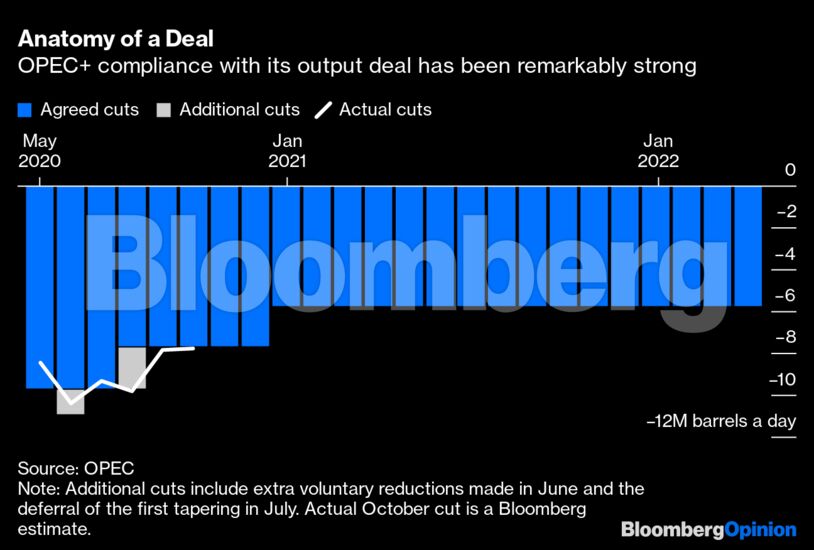

Compliance with the deal has been remarkably good, due in no small measure to the determination of Saudi Energy Minister Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman to hold everyone’s feet to the fire. He’s publicly called out those who have fallen short, demanding they make up for any lapses. Some countries, like Iraq, have struggled to deliver the compensatory cuts, but they’ve probably made more of an effort thanks to the Saudi spotlight.

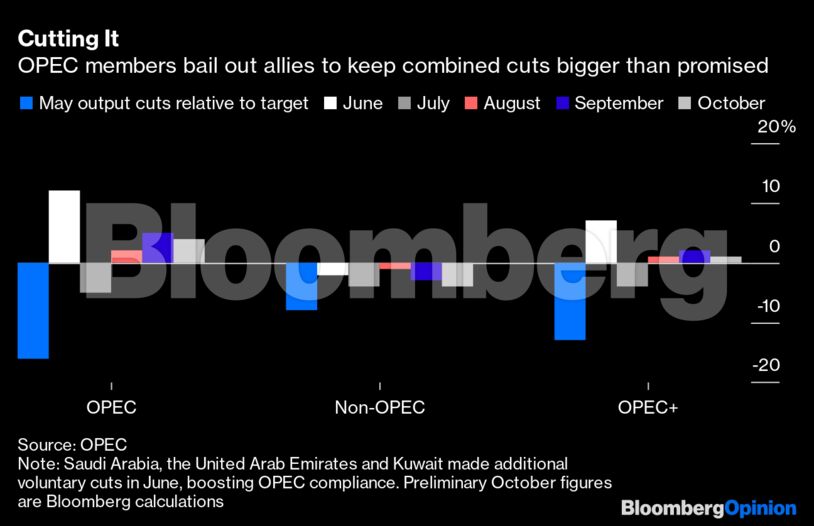

The one non-OPEC country that has escaped reprimand is Russia, even though it has, on average, pumped nearly 100,000 barrels a day more than its target since May. The transgression may be small in percentage terms — the country’s initial output cut was just over 2.5 million barrels a day — but its over-production is the second largest in volume terms among the whole group. You could be forgiven for thinking Russia’s getting special treatment as such an important new ally.

OPEC’s members have been better at meeting their obligations and it is their over-compliance — led by Saudi Arabia — that has helped the wider group to beat its target in each of the past three months.

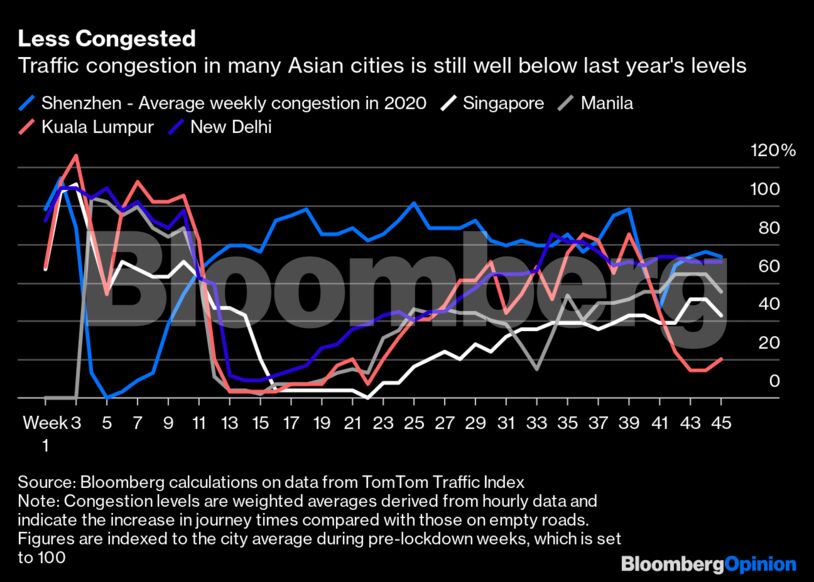

The pandemic’s persistence means the producers can’t relax just yet. Oil demand hasn’t recovered as fully, or as rapidly, as they’d hoped. The coronavirus’s second wave has led to renewed travel restrictions in Europe and may trigger similar moves in the U.S. Even in Asia, where the recovery is seen as stronger, traffic levels remain significantly below year-ago levels in many cities, according to figures from TomTom Traffic Index.

Even though oil demand in both China and India has topped year-ago levels, the picture for crude suppliers remains shaky. In its latest monthly report published on Thursday, the International Energy Agency noted that while refiners in Asia are expected to be operating next year at close to 2019 levels, processing in the Atlantic Basin (mostly Europe and the Americas) will remain at its lowest level for two decades.

And it’s refiners, not motorists, who are the oil producers’ customers. Russia and Nigeria, most exposed among the OPEC+ members to the Atlantic market, have a lot to worry about.

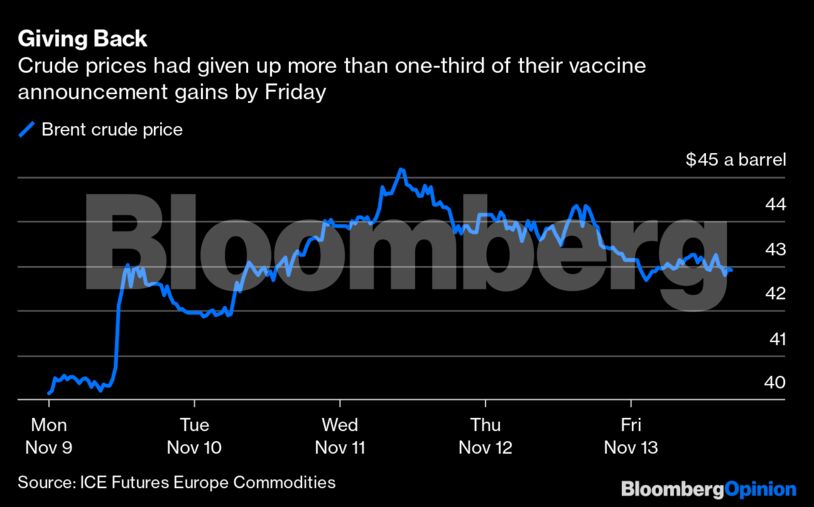

It’s little surprise, then, that the OPEC+ group is getting concerned. More than a third of the surge in crude prices that followed Monday’s vaccine announcement had been given up by Friday.

Even if all the vaccines being tested are as effective as the Pfizer Inc. and BioNTech SE shot — and let’s hope they are — it will still be many months before enough people have been inoculated to alter the pandemic’s path significantly. Until then, the types of restrictions that have slashed oil demand this year remain key tools to slow the virus’s spread. That’s a problem for producers.

Their second big headache, as I mentioned last week, is rising supply. Libya, not shackled by the OPEC+ agreement, is restoring production much more quickly than many anticipated after a devastating civil war. Production on Friday reached 1.145 million barrels, up from the just 90,000 barrels a day it was pumping in September. Now that rival factions in the North African country reached a preliminary agreement with a goal of holding elections within 18 months, there are hopes this peace deal, and the oil production that goes with it, will last.

Suffice it to say that OPEC+ oil ministers can’t afford to relax their output restraint in January. They’re unlikely to try to agree to deepen the cuts — that would open too many arguments at a time when they need to show unity and clarity of purpose. Their only realistic option is to delay the tapering of cuts, with the only real question they have to answer: For how long? Covid continues to provide a major impetus for this often quarrelsome group to show an unusually united front.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Busting Biases, Boosting Innovation – Geoffrey Cann