By David Fickling

Capital markets are taking notice. ConocoPhillips announced Monday that it would buy Concho Resources Inc. for about $9.7 billion in stock, helping consolidate the two companies’ acreage in the Permian. Just three weeks ago, Devon Energy Corp. spent $2.56 billion in shares buying WPX Energy Inc., building its position in one of the lower-cost districts of the Permian. Parsley Energy Inc., one of the remaining minnows in the basin, is in talks about a takeover by Pioneer Natural Resources Co., the Wall Street Journal reported late Monday.

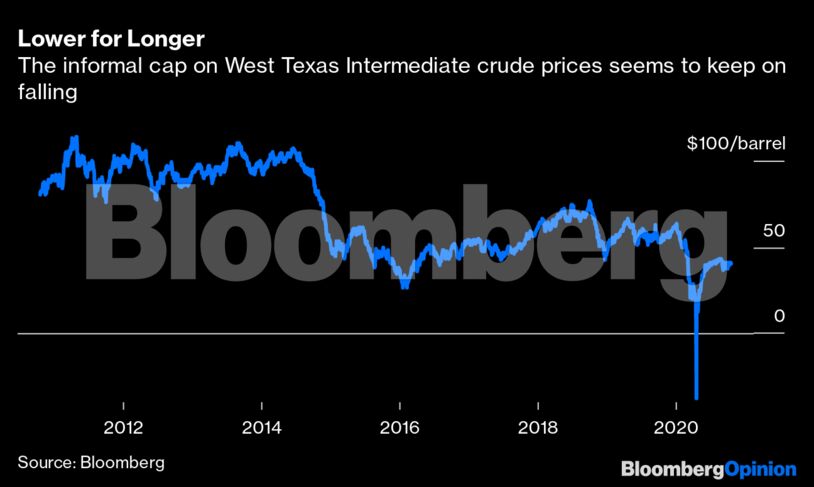

As we’ve argued, life is much more manageable in the range of $40 a barrel than many would have expected a few months ago.

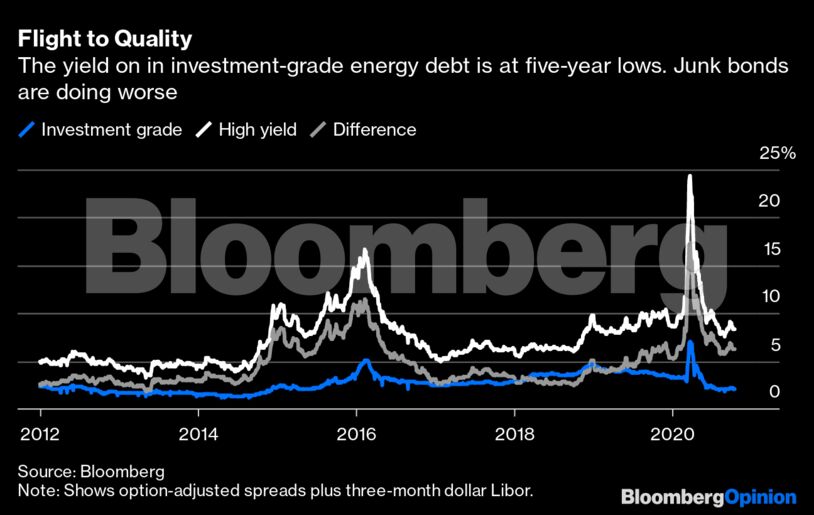

For exploration and production companies, the size of your balance sheet is probably as important as the size of your reserve base at the moment.

Thanks to the slump in interest rates this year, investment-grade energy companies can borrow as cheaply as at any point since before the last oil price crash in 2015, based on the pricing of option-adjusted spreads. Meanwhile, junk-rated energy debt has settled at far higher rates, increasing the advantage for the big end of town. In both the ConocoPhillips-Concho and Pioneer-Parsley deals, we’re seeing companies with relatively comfortable investment-grade ratings buying smaller rivals on the verge of relegation to junk.

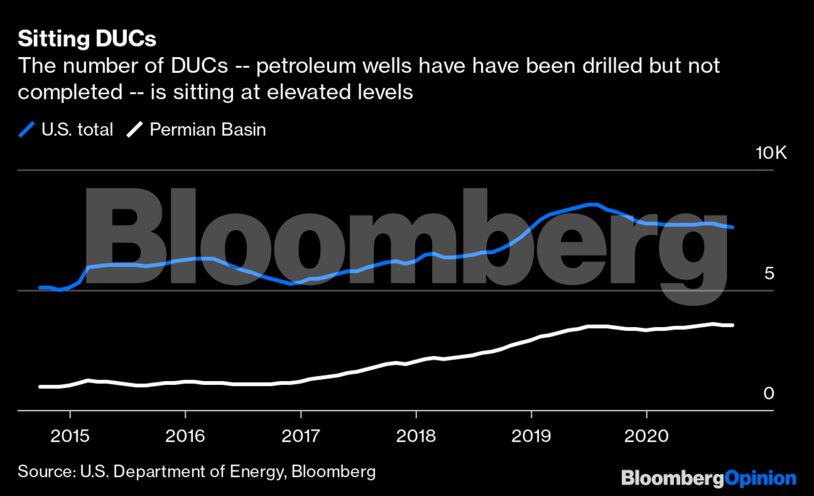

Once borrowing costs are brought under control, it’s not nearly such a challenge to keep pumping out barrels. The so-called fracklog — drilled but uncompleted wells that could be put into action the moment prices rise far enough to cover their operating costs — remains at elevated levels, with July seeing a record number in the Permian basin. Working through that overhang will be enough to sustain output for some time, even in the absence of aggressive drilling activity. Around 80% of the fracklog is able to break even at prices below $25 a barrel, consultants Rystad Energy estimated in March.

That won’t be enough to keep the oil flowing forever, and earlier-stage activity to develop new wells is still relatively subdued. The number of land-based exploration rigs in operation across the U.S. has risen in six of the past nine weeks, but it’s still running at about a third of the levels seen before March’s price crash. Drillers need prices above $50 a barrel before exploration activity picks up substantially, based on the predominant views expressed in a survey of the industry by the Federal Reserve of Dallas last month.

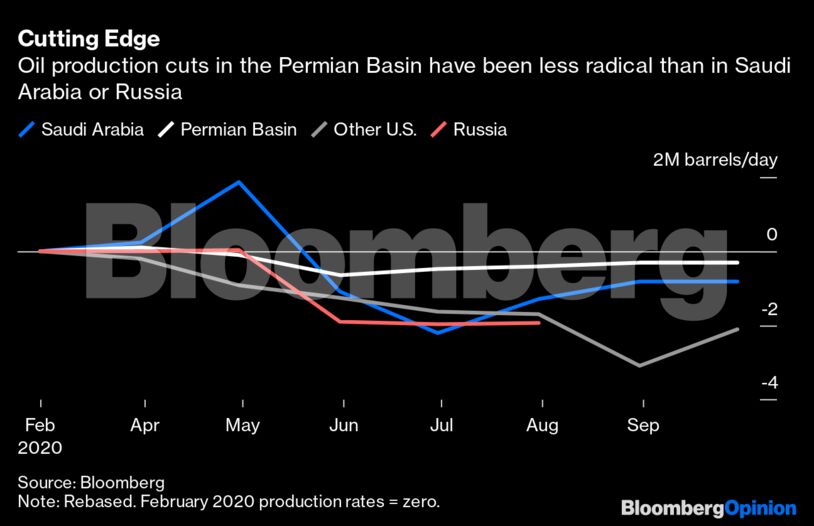

Still, that should be cold comfort to oil producers elsewhere in the world. Most members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries need prices north of $60 a barrel to balance their budgets. If $50 is sufficient to kick off a new flood of supply from U.S. shale basins, OPEC members are going to need to force through spending cuts even more radical than the ones they’re already planning. Meanwhile, the consolidation of the U.S. upstream industry from the current wave of deal-making may further reduce its cost structure into the $40s, or even below that.

The Hail Mary pass made by the world’s oil exporters in March was that a flood of output would be sufficient to squash the U.S. oil patch for good. That would give OPEC members a chance to build their market share, helping them prop up prices through the inevitable decline of oil demand as the world decarbonizes.

It’s not working out that way. Instead, an informal price cap imposed by U.S. shale appears to have grown tighter, from around $60 a barrel between 2015 and 2019 to $50 or less now. Contrary to false statements by President Donald Trump, a Joe Biden presidency won’t ban fracking, either — indeed, as my colleagues Liam Denning and Julian Lee have argued, a more even-handed government may ultimately help the oil industry by pointing a clear path through the transition away from fossil fuels.

That may not be a bad thing for the global climate, either. From the perspective of a planet eking out the last of its carbon budget, an industry skewed toward shale wells that exhaust themselves in a few years may well be preferable to one where large companies are still signing off on major conventional fields that can keep producing for decades.

This year’s glimpse into the abyss of an oil glut didn’t kill the shale industry. Instead, it may have only made it stronger.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Fossil Fuels Show Staying Power as EU Clean Energy Output Dips – Maguire