By Zainab Fattah and Abeer Abu Omar

“Dubai is home for me,” said Sissons, who owned a small cafe and worked as a freelance human resources consultant. But “it’s expensive here and there’s no safety for expats. If I take the same money to Australia and we run out of everything, at least we’ll have medical insurance and free schooling.”

It’s a choice facing millions of foreigners across the Gulf as the fallout from the pandemic and a plunge in energy prices forces economic adjustments. Wealthy Gulf Arab monarchies have, for decades, depended on foreign workers to transform sleepy villages into cosmopolitan cities. Many grew up or raised families here, but with no formal route to citizenship or permanent residency and no benefits to bridge the hard times, it’s a precarious existence.

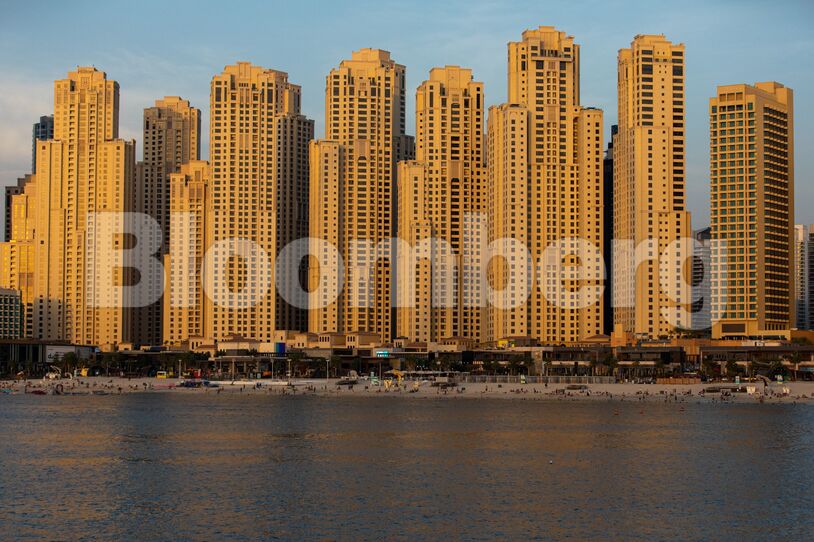

The impact is starkest in Dubai, whose economic model is built on the presence of foreign residents who comprise about 90% of the population.

Oxford Economics estimates the United Arab Emirates, of which Dubai is a part, could lose 900,000 jobs — eye-watering for a country of 9.6 million — and see 10% of its residents uproot. Newspapers are filled with reports of Indian, Pakistani and Afghan blue-collar workers leaving on repatriation flights, but it’s the loss of higher earners that will have painful knock-on effects on an emirate geared toward continuous growth.

“An exodus of middle class residents could create a death spiral for the economy,” said Ryan Bohl, a Middle East analyst at Stratfor. “Sectors that relied on those professionals and their families such as restaurants, luxury goods, schools and clinics will all suffer as people leave. Without government support, those services could then lay off people who would then leave the country and create more waves of exodus.”

With the global economy in turmoil, the decision to leave isn’t straightforward. Dubai residents who can scrape by will likely stay rather than compete with the newly unemployed back home. The International Labor Organization says more than 1 billion workers globally are at high risk of pay cuts or job losses because of the coronavirus.

Some Gulf leaders, like Kuwait’s prime minister, are encouraging foreigners to leave as they fret about providing new jobs for locals. But the calculation for Dubai, whose economy depends on its role as a global trade, tourism and business hub, is different.

The crisis will likely accelerate the UAE’s efforts to allow residents to remain permanently, balanced against the status of citizens accustomed to receiving extensive benefits since the discovery of oil. For now, the UAE is granting automatic extensions to people with expiring residence permits and has suspended work-permit fees and some fines. It’s encouraging local recruitment from the pool of recently unemployed and has pushed banks to provide interest-free loans and repayment breaks to struggling families and businesses.

A Dubai government spokesperson said authorities were studying more help for the private sector: “Dubai is considered home to many individuals and will always strive to do the necessary to welcome them back.”

Dubai’s main challenge is affordability. The city that built its reputation as a free-wheeling tax haven has become an increasingly costly base for businesses and residents. In 2013, Dubai ranked as the 90th most expensive place for expatriates, according to New York-based consultant Mercer. It’s now 23rd, making it the priciest city in the Middle East, though it slipped from 21st place in 2019 as rents declined due to oversupply.

Education is emerging as a deciding factor for families, especially as more employers phase out packages that cover tuition. Though there’s now a wider choice of schools at different price points, Dubai had the region’s highest median school cost last year at $11,402, according to the International Schools Database.

That will likely lead parents to switch to cheaper schools and prompt cuts in fees, according to Mahdi Mattar, managing partner at MMK Capital, an advisory firm to private equity funds and Dubai school investors. He estimates enrollments may drop 10%-15%.

Sarah Azba, a teacher, lost her job when social distancing measures forced schools online. That deprived her of an important benefit; a free education for her son. So she and the children are returning to the U.S., where her 14-year-old son will go to public school and her daughter to college. Her husband will stay and move to a smaller, cheaper home.“Separating our family wasn’t an easy decision but we had to make this compromise,” Azba said.

For decades, Dubai has thought big, building some of the world’s most expansive malls and tallest buildings. From the desert sprang neighborhoods lined with villas designed for expat families lured by sun and turbo-boosted, tax-free salaries. New entertainment strips popped up and world-class chefs catered to an international crowd. But the stress was building long before 2020. Malls were busy but shoppers weren’t spending as much. Residential properties were being built but there were fewer buyers. New restaurants seemed to cannibalize business from old.

The economy never returned to the frenetic pace it enjoyed before the 2008 global credit crunch prompted the last bout of expatriate departures. Then, just as it turned a corner, the 2014 plunge in oil prices set growth back again. The Expo 2020, a six-month exhibition expected to attract 25 million visitors, was supposed to be a reset; it’s now been delayed due to Covid-19.

Weak demand means recovery will take time. Unlike some Middle Eastern countries, the UAE isn’t seeing a resurgence in Covid-19 infections as it reopens, but its reliance on international flows of people and goods means it’s vulnerable to global disruptions.

Emirates Group, the world’s largest long-haul carrier, is laying off employees as it weighs slashing some 30,000 jobs, one of the deepest culls in an industry that was forced into near-hibernation. Dubai hotels will likely cut 30% of staff. Developers of Dubai’s man-made islands and tallest tower have reduced pay. Uber’s Middle East ride-hailing unit Careem eliminated nearly a third of jobs in May but said this week business was recovering.

Dubai-based Move it Cargo and Packaging said it’s receiving around seven calls a day from residents wanting to ship their belongings abroad. That compares with two or three a week this time last year. Back then, the same number of people were moving in too. Now, it’s all outward bound.

Marc Halabi, 42, spent the past week reluctantly sorting belongings accumulated over 11 years in Dubai. Boxes line the rooms as he, his wife and two daughters decide what to ship back to Canada. An advertising executive, Halabi lost his job in March. He’s been looking for work that would allow the family to remain but says he can’t afford to hold out any longer.

“I’m upset we’re leaving,” Halabi said. “Dubai feels like home and has given me many opportunities, but when you fall on hard times, there isn’t much help and all you’re left with is a month or two to pick up and move.”

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS