By Julian Lee

Sure, many of us will return to our pre-Covid-19 ways of life just as quickly as we can, but others will gladly give up the daily commute in favor of working from home more often — and employers may be happy to accommodate their wishes. After months of successful teleconferencing, those business trips that helped keep planes full of high-paying travelers may also come under more scrutiny. These changes may push up electricity use while they dampen fuel demand, but that will do little to help the oil industry, which is increasingly struggling to hold onto its fragments of the power-generation sector.

Of course, we could collectively shrug off this latest crisis, just as we did the financial crash of 2008-09, which was consigned to history with barely a backward glance. But the global pandemic feels very different from the financial crisis. It hits at our physical well-being as well as our financial health, and it has forced us all, to one degree or another, to adopt new ways of living and working, whether we like them or not.

The industry can survive a 5% drop in long-term demand, but it will find it much harder to thrive.

A loss like that will cause structural overcapacity, right through the oil supply chain. There will be too many wells to get oil out of the ground, too many ships to move it, too many refineries to process it.

Even before the pandemic, we were looking at a world where oil demand growth was increasingly concentrated in plastics, rather than fuels. That was already darkening the outlook for refiners in Europe and North America, which were also facing growing competition from newer plants in the Middle East and Asia that were more efficient and had beneficial long-term oil supply deals. A prolonged drop in demand will only make that competition stiffer, as more plants seek markets for their excess products.

The upstream part of the business — the bit that’s concerned with finding the crude and getting it out of the ground — may face fewer problems. Oil fields naturally go into decline once they’re brought into operation, requiring producers to create new capacity elsewhere. Nowhere is that more obvious than in the U.S. shale patch.

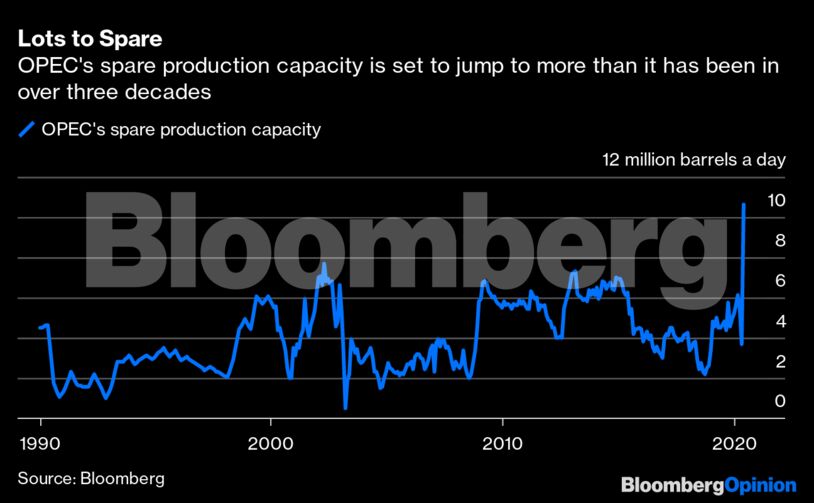

But the second U.S. shale boom was driven by, among other things, several years of robust growth in global oil demand. This led to most of the world’s oil producers, including almost all of the OPEC countries, pumping as hard as they could, and helped to keep oil prices at around $50 a barrel.

But those OPEC producers are now cutting production by more than 20%, and non-OPEC countries are seeing their output fall by similar percentages. True, some of the wells that get shut will never be reopened, but most will sit waiting for their owners to see an opportunity to get them back to work. That overhang of spare production capacity will put an effective cap on oil prices, just as it did throughout the 1990s.

No amount of Saudi-led supply management, or U.S. presidential bullying of foreign oil producers, will be able to remove that spare capacity. And once the current crisis is past, Riyadh may be less willing to play the role of swing producer, restraining its output while everybody else reopens the taps.

Every time oil prices rise, producers will rush to use their idled capacity, undermining the recovery. After the oil-price slump of the mid-1980s, it took two decades for prices to return to their previous levels — longer if you build in the effects of inflation. This time the wait could be even more protracted.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Fossil Fuels Show Staying Power as EU Clean Energy Output Dips – Maguire