By Julian Lee

The situation has arisen because there is still simply too much crude being produced in a world that can’t use it.

The output cuts agreed to on April 12, after a four-day standoff between Mexico and the other members of the OPEC+ alliance, haven’t yet made a barrel of difference to supplies. They are only just starting to be implemented by a handful of the participants, with most — including the two biggest, Saudi Arabia and Russia — unlikely to make meaningful reductions before the deal officially comes into force on May 1. Meanwhile, about 40 million barrels of Saudi crude is heading for the U.S., alongside at least 11 million barrels from Iraq, all of it due to arrive by the start of June.

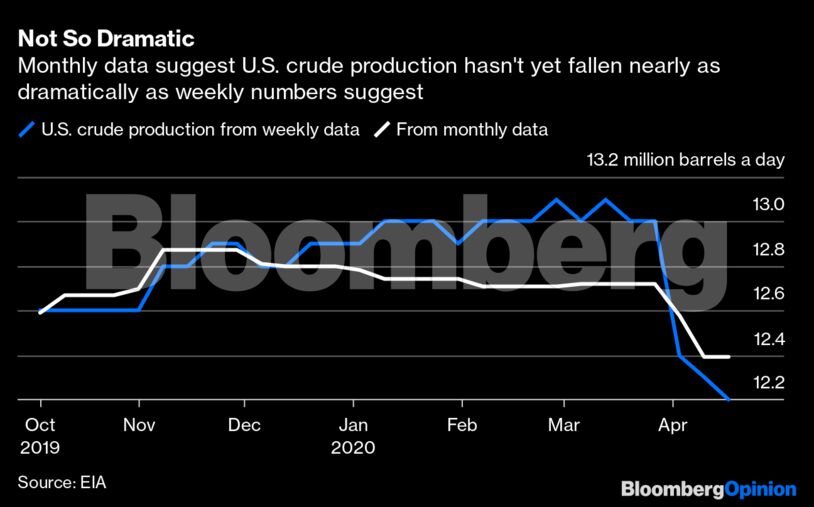

Signs elsewhere are just as discouraging. Non-OPEC producers simply aren’t reacting quickly enough. U.S. production hasn’t fallen nearly as dramatically as weekly data from the Energy Information Administration appear to show. More comprehensive monthly data from the same source suggest the drop is about half of that implied by the weekly numbers and over a period that’s four times as long.

My colleague David Fickling notes that other benchmark crude grades, such as North Sea Brent, don’t have the same physical delivery requirements as WTI, which may give them some protection from falling into negative territory. But Intercontinental Exchange Inc., a leading provider of online marketplaces and clearing services for global commodity trading, is already preparing Brent crude contracts for negative trading. And some physical crudes priced at big discounts to Brent are already very close to zero.

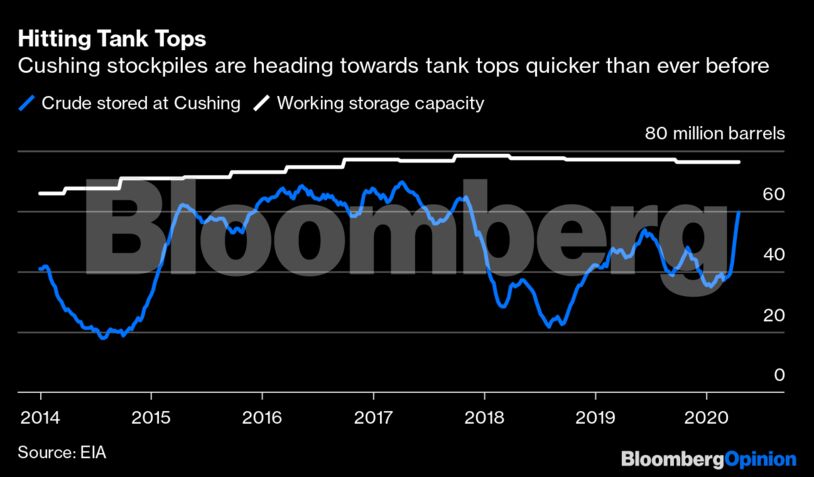

Meanwhile, the lack of storage space at Cushing that triggered WTI’s sub-zero dive doesn’t look likely to improve by the time the June contract expires, although the realization that prices can actually turn negative may help avoid a repeat in mid-May.

But it’s not just at Cushing that storage capacity is running out. Indian storage tanks are nearly full. Tankers full of crude are starting to build up off the coasts of America and well-known floating storage areas like South Africa’s Saldanha Bay. Even where there is still space in tanks, it has mostly already been reserved, making it unavailable for use.

Desperate times call for desperate measures. In Europe, refined products are even being stored on barges. In the U.S., pipeline operator Energy Transfer LP is looking to free up space in its conduits in Texas to store 2 million barrels of crude. And a director of Ukraine’s state-owned oil company Naftogaz Ukrainy has suggested storing non-Russian crude in an underutilized pipeline network, which could theoretically hold as much as 35 million barrels.

Even solutions like these will only delay the inevitable. Unless producers start cutting supply much more aggressively, another bout of negative prices will have to jolt them into action.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Where the Fight Against Energy Subsidies Stands – Alex Epstein