By Liam Denning

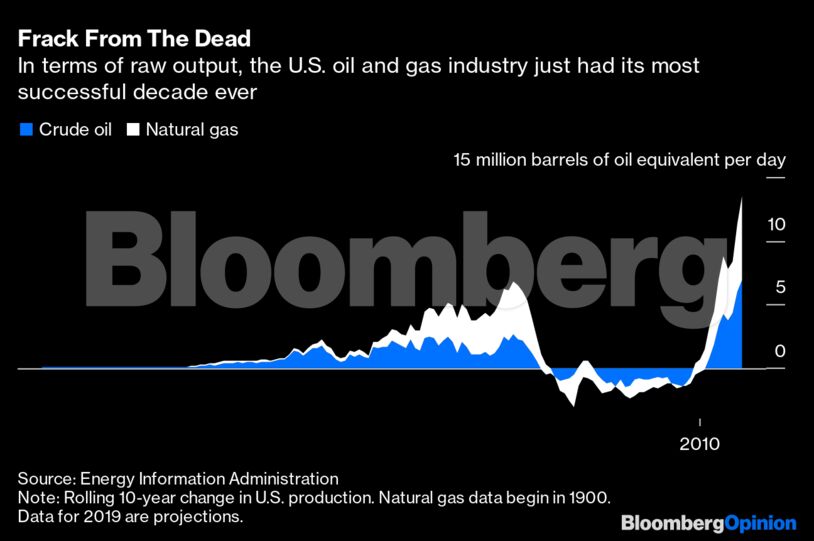

In certain respects, tight oil and gas is ideal for energy dominance. Reserves are vast while output is both prodigious and reacts relatively quickly to changes in oil and gas prices. The wave of supply has flattened those prices, to the benefit of suddenly less-anxious American drivers and, as exports rise, the detriment of bogeymen like OPEC. It doesn’t get much more MAGA than that.

The catch? Many frackers were so busy growing they forgot the part about building sound business models. Even before coronavirus showed up, capital markets had backed away from the sector, withdrawing the funds vital to bridging the gap between income and spending (see this). The twin shocks of coronavirus and the Saudi-Russian price war have hit an industry made vulnerable by its own excesses and reliance on OPEC or capital markets to head off any disruption. With E&P companies now competing on how quickly they can cut budgets rather than spur growth, output will fall, jobs will be lost and some firms will disappear altogether. Hence the turn to Washington.

President Donald Trump’s immediate plan manages to murder irony by buying U.S. oil for the Strategic Petroleum Reserve. The SPR is that ‘70s symbol of vulnerability the administration had been liquidating in our new era of “dominance.”The Feds now aim to buy oil for the strategic reserve in order to shore up the fracking revolution that was going to render it obsolete.

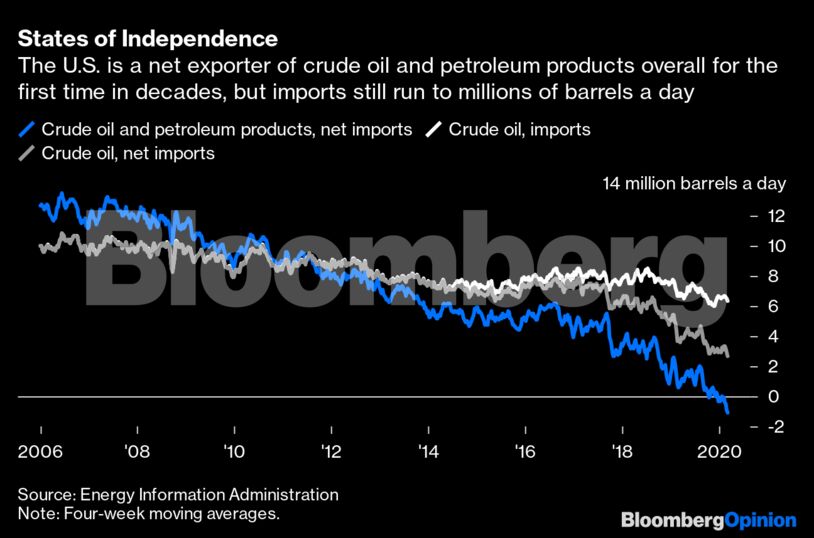

In an extreme supply shock, such as during a major war, America’s capability to cover its own energy needs for an extended period is far stronger today than just 10 years ago. At best, though, that’s a narrowly defined, costly, likely state-directed form of energy independence for a specific situation, not dominance. In the normal course of things, the U.S. remains energy interdependent because, as with most supply chains, that’s a more efficient path. This is why the U.S. is now a net exporter of crude oil and petroleum products but still imports about six million barrels a day of crude; the sort of nuance that gets lost in a political slogan.

As shale’s current predicament shows, fetishizing sheer output comes at a steep price. This is why Russia and Saudi Arabia boast of their ability to withstand the inevitable economic hit that will come from their price war by digging into savings — and both of those remain on my handy list of economies not to emulate.

The contradictions and weaknesses of energy dominance have been evident from the get-go. Trump’s first energy secretary, Rick Perry, expended much energy of his own trying to craft creative regulatory crutches to support the ailing U.S. coal mining industry, which ails in large part because of the fracked natural gas the administration also champions. Efforts on coal’s behalf continue at the state level; just last week the Indiana state senate passed a measure that would give regulators the right to simply block closures of coal-fired plants. Meanwhile, with oil, the Trump administration fights to roll back vehicle-mileage targets, even though efficiency gains, in bending the demand curve down, offer the most sustainable route to anything approaching energy independence.

A mandate here, an SPR-fill there and who knows what else to come. Energy dominance is just a new bumper sticker promoting the same old objective: government support for domestic fossil fuels whenever competition or some other disruption threatens, be it a novel virus or novel energy technologies or usage patterns. It remains deeply strange, if drearily predictable, that this most advanced of economies should have a federal energy policy — in the loosest sense of the word — prioritizing technologies and extractive industries which were cutting-edge a hundred years ago while frequently undercutting emerging ones.

For those vulnerable oil champions nonetheless hopeful of a new handout, there is a bigger question they should be considering. What does it say about the health of their sector that the big three actors on the global stage today consist of a shale industry with a chronic balance sheet problem and two sclerotic petrostates playing chicken with their foreign-exchange reserves?

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

Trump Is Scaring Republicans Away From Saving the Planet