By Ben Steverman

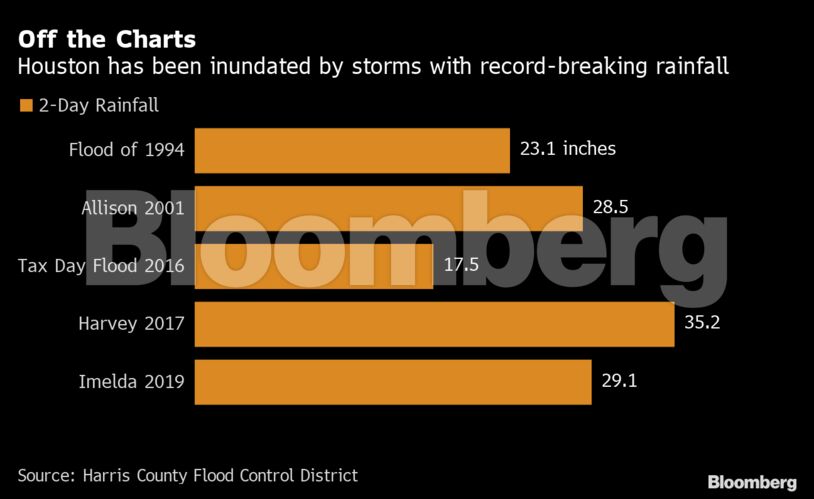

Climate change is a touchy topic in Houston, even if hardly anyone doubts the climate is changing. An already damp city is getting wetter, obvious in the muddy sidewalks and the puddles that linger long after a routine rain. The bigger downpours block highways. The really huge storms—and not just 2017’s Hurricane Harvey, which killed at least 94 people—keep arriving with a size and frequency that meteorologists once insisted was impossible. With initial support from Texas’s governor and U.S. senators (all conservative Republicans), the Army Corps of Engineers wants to spend $23 billion to $32 billion on a coastal bulwark against the rising waters.

Say “climate change” too loudly, though, and you’ll get some looks. Many Houstonians still feel like they’re in a standoff with environmentalists who would love to put the Oil and Gas Capital of the World out of business. And anyway the city is booming, with cranes as common as traffic jams on its ever-widening highways. With a population up 11% since 2010, Houston is destined to overtake Chicago as the U.S.’s third-largest city—unless something goes horribly wrong.

Something horrible like the worst environmental disaster in American history, which is just one of the looming catastrophes that Jim Blackburn won’t shut up about. The environmental lawyer and Rice University professor shows up everywhere in Houston—at society events, on the radio, in op-eds and at government hearings—and blurts out what the city’s elite, its oil and gas executives, only whisper in their board rooms: Climate change is an existential threat to Houston, putting in real danger both its physical survival and its economic future.

In his Texas twang, Blackburn, a 72-year-old native of the Rio Grande Valley, warns that the Army Corps’ coastal barrier is insufficient. The region’s flood maps are wrong, making new infrastructure, designed to last decades, obsolete the day it’s finished. Renewable energy is getting cheaper, and climate activists are getting louder. Without creative thinking, the fossil fuel industry will collapse, and Houston will turn into a warmer, wetter rust belt.

“There’s a void in Houston right now of leadership,” Blackburn says. “That’s what allows a voice like mine to resonate a bit. I’m saying things that other people are not saying.”

He’s backed by hydrologists, weather modelers, engineers, and ecologists, at Rice University and elsewhere, who produce a steady stream of terrifying research. The main takeaway is that the state’s politicians and businesses are still operating on data from the past century, an era before the weather went berserk.

This is hardly the first time that Blackburn has told Houston’s bigwigs that they’re falling short. He’s been suing them for decades. “Jim is a badass,” says Adrian Garcia, a Harris County commissioner and former Houston council member who remembers the prospect of Blackburn’s meeting appearances causing heartburn for city officials. “He is immensely respected and has a reputation for being a hard charger and taking no prisoners.”

What’s unusual lately is the respectful reception that he’s getting not just in city government—long dominated by Democrats—but elsewhere around town. Powerful people are listening—or at least pretending to.

The prophet of Houston’s doom can sound upbeat, even chipper, talking about the opportunities for a greener future. He has two different projects to shrink the state’s giant carbon footprint by storing CO₂ naturally in marshes and ranchlands. The ideas have the advantage of being cheaper than high-tech alternatives and creating a new climate constituency among the private landowners who sign up to get paid for their “ecological services.”

Blackburn is full of other notions, too: Ways to deal with flooding in urban areas, and shore up the local economy by stimulating eco-tourism on the coast, and re-tool the plastics industry—a research project funded by a huge plastics-maker that he once spent years fighting in court.

Blackburn’s secret, says former Mayor Annise Parker, is that he is translating his uncompromising environmentalism into a language that Houston’s establishment understands: money. “If you can make a business argument,” she says, “the business community will hear you out.”

First, though, Blackburn tells everyone who will listen that Texas must deal with a more-immediate danger: The next hurricane.

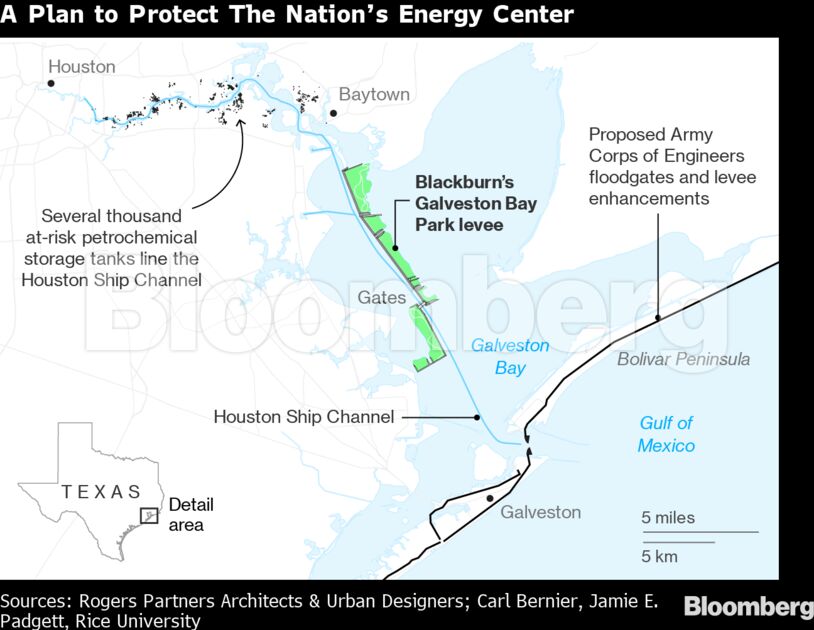

Blackburn’s proposed solution is ambitious, to say the least: Plop a new 10,000-acre land mass in the middle of a bay. It would become public park lined with wetlands, but its main function would be to stop a storm from ruining Houston’s economy with one giant wave.

Houston’s geography was shaped by tragedy. It’s 50 miles from the Gulf of Mexico and from Galveston, formerly Texas’s biggest port and largest city. In 1900, a hurricane drowned Galveston under a 16-foot storm surge, killing roughly 8,000 people. The shipping industry moved inland, and Houston began its rise, eventually becoming the place Texas sends its oil, gas, plastics, and petrochemicals out into the world.

Texans will tell you their state’s economy has diversified beyond fossil fuels. Austin has tech. Dallas has finance. Even Houston, with its sleek office towers and sprawling suburbs, can feel far from the oil patch. Yet the Texas Oil and Gas Association boasts the industry still directly or indirectly accounts for 30% of the state’s economy. Surveying the edges of Houston’s Ship Channel—a knot of refineries, railyards, chemical factories, plastic plants, and storage tanks—that estimate begins feeling rather low.

For decades as a lawyer, Blackburn battled these facilities and anything else that threatened to foul the air, water or land. His adversaries were the world’s largest companies. His clients in the early days were neighbors and nature lovers, who paid him in tamales, raffle proceeds, and shrimp harvested from the bay. (He’s done better more recently. One of his cars is a Tesla Model 3.)

Over the years, his lawsuits have helped close landfills, re-routed pipelines, and got refineries to cut emissions and compensate communities they polluted. He has negotiated settlements that saved thousands of acres from development, and protected endangered whooping cranes. In 2007, he got one of the world’s largest refineries, in Port Arthur, Texas, to cut its emissions while contributing millions of dollars to a development fund for the low-income neighborhood in its shadow.

Still, he’d often lose. He dealt with disappointment through the occasional, and then frequent, drink. When he started attending Alcoholics Anonymous in 1986, he struggled with the idea of relying on a higher power—until he realized Galveston Bay and the other Texas Coast waterways could be his guiding force. When he wanted another drink, he’d launch his kayak into a marsh and fish alongside reddish egrets and tricolored heron.

He self-publishes his own poetry in books illustrated by a painter friend. On a walk along the bay in December, Blackburn spots a white-tailed hawk on the site of a proposed copper plant he helped to quash. “It is an absolute nature wonderland,” he says. Later, he writes a poem about the bird.

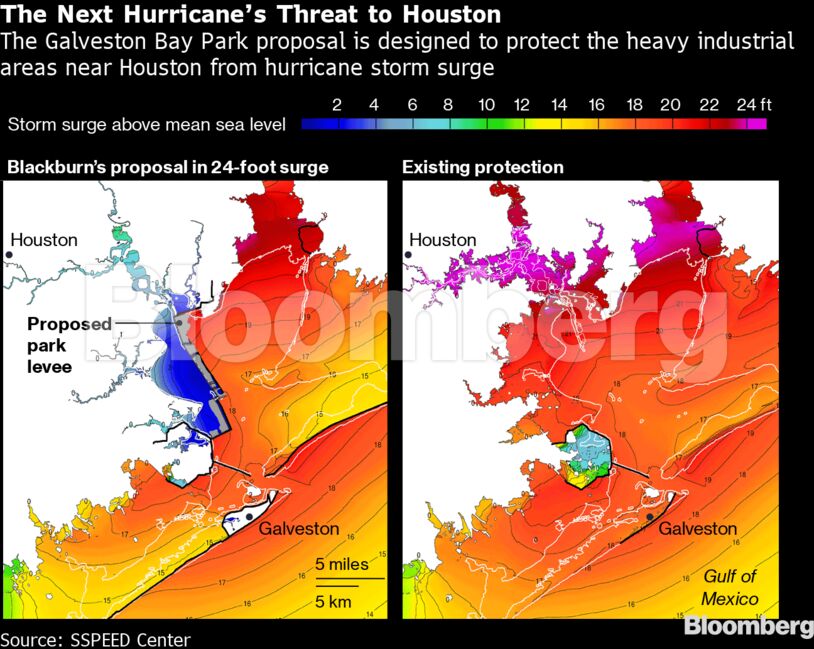

It’s all at risk in the next big storm. Nearby, there are about 4,400 giant storage tanks holding oil and hazardous chemicals, alongside refineries pumping out 2.2 million barrels of fuel per day. Many complexes here are only designed to withstand a 15-foot storm surge. One estimate says a 25-foot surge would inundate half of the area’s storage tanks and spill more than 100-million gallons into the channel and bay. It would take a weak Category 4 hurricane to produce a 25-foot high surge, and that would be smaller than the three Category 5 hurricanes that hit the Caribbean recently—Irma and Maria, in 2017, and Dorian in 2019.

“If this storm comes, this will be the worst environmental disaster in U.S. history,” Blackburn says.

He’s not alone in that assessment. “This is a very real threat,” says Bob Harvey, president and CEO of Greater Houston Partnership, the region’s main business organization. “We need to be doing something. We need to be doing it now.”

A barrier down on the coast isn’t enough to prevent it, according to models from Rice University’s Severe Storm Prediction, Education, and Evacuation from Disasters, or SSPEED, Center, of which Blackburn is co-director. A hurricane could create an unprecedented surge within the bay even if you block water from the Gulf. What’s needed, Blackburn says, is another barrier in Galveston Bay, a string of new islands, created by dredging, that would absorb a storm surge while creating acres of nature and parkland.

Blackburn’s solution follows advice to Houston from the Dutch, who have learned to protect the low-lying Netherlands with “multiple lines of defense,” says Charlie Penland, the director of civil engineering at Walter P. Moore, who helped come up with the plan. “If something fails, we’ve got to have all these back-ups.”

The idea is being taken seriously. “It’s a great plan,” says Ric Campo, chairman of the Port of Houston Authority commission, “but what we need to do is further study it, so you can actually prove that it can be built without significant environmental impacts and at a price that makes sense.” The current, preliminary estimate of $3 billion or more is far less than the cost of the Army Corps’ plan, perhaps unrealistically so.

Federal money, if it comes at all, would likely go toward the coastal barrier, so Blackburn is looking for creative funding. He’s raised the idea of special taxing districts or social impact bonds that would pull money from the industry his plan would protect. He’s hoping Houston’s Harris County, which recently passed a $2.5-billion bond for flood protection, can jump-start serious consideration.

That’s more likely since Blackburn helped clear a major impediment. The Army Corps of Engineers declared his Galveston Bay Park compatible with its own efforts, easing many politicians’ concerns that they had to choose between the two. “It’s not the answer; it’s part of the answer,” says Garcia, the county commissioner who represents areas along the Ship Channel. “We need a multi-pronged approach to dealing with these kind of challenges.”

While Blackburn celebrates this progress, he also worries that everyone is moving far too slowly—setting Houston up for a fate not unlike that of Galveston. “There does not seem to be any sense of urgency,” he says.

“I’ve always sued oil companies,” Blackburn says. Now, however, he’s being invited inside their headquarters to help his old foes grapple with their futures in a warmer world. He’s met with a dozen major and minor oil companies in Houston, including very senior executives, about Soil Value Exchange, his plan to store carbon dioxide by paying ranchers to restore the CO₂ in their depleted soils. (So far, he’s got no takers, and there’s more work to do on the standards and science behind the idea.)

In private, oil-and-gas executives have worried for a while about climate change. They’re only just starting to acknowledge the threat in public.

“It’s an intense dialogue we’re having in Houston about how do we participate in the transition to a low carbon or net zero carbon world,” says Harvey, of Greater Houston Partnership. “We don’t disagree at all on the necessity of addressing the carbon issue.” He acknowledges his members would have objected to that kind of statement even two or three years ago.

Years after major European oil companies proclaimed they were getting serious about climate change, the big American firms now say the same thing. Chevron, Exxon Mobil, and Occidental Petroleum have signed onto the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative, or OGCI, promising to reduce methane emissions and pitching into a $1 billion-plus fund for emission-cutting technologies. One of OGCI’s initiatives would make the Gulf Coast of Texas and Louisiana into a hub for carbon capture, utilization and storage, or CCUS, a method of capturing CO₂ from smokestacks and other emitters and then injecting it into the ground.

Many environmentalists are skeptical, to say the least, of oil-and-gas’s new climate-friendly pose. U.S. fossil fuel companies still spend just a tiny fraction of their research-and-development budgets on green technologies. In fact, most spending on CCUS goes to “enhanced oil recovery,” which is pumping carbon dioxide into the ground in a way that makes wells more productive. Less carbon dioxide in the air now, but more polluting fuel to burn later.

Even as trillions of dollars are expected to pour into renewables, U.S. industry is betting its future on finding new markets for the glut of oil and gas it produces: The Port of Houston, already the U.S.’s busiest by vessel traffic, plans a major expansion so more can be exported abroad.

Blackburn worries about what he believes could be a fatal complacency. “They’re not thinking creatively,” says Blackburn. “We’re going to have to find the solutions and basically put them on a plate for the industry.”

One such solution is regenerative agriculture. The world’s topsoils hold more carbon than the atmosphere. Many environmental groups and scientists believe better farming techniques could pull far more CO₂ into the ground, while also enhancing productivity and biodiversity. By grazing cattle differently, for example, Project Drawdown, a group working on responses to climate change, estimates ranchers could sequester 16.34 gigatons of CO₂ by 2050.

Blackburn’s idea, Soil Value Exchange, is a marketplace to match ranchers, and perhaps eventually farmers, with companies that want to offset their carbon footprints. A Rice University group is working on rules that are flexible enough to work but strict enough to combat the concerns about greenwashing that have plagued some offset programs.

Texas has the largest carbon footprint in the country, but the state also produces more wind power than any other. It’s so sunny that, in theory, a hundred-mile-wide square of solar plants in West Texas could produce enough energy to power the lower 48 states. That makes it crucial for the battle over climate change.

“What happens in Texas will likely determine the future of the U.S. over the next decade,” says Katharine Hayhoe, the co-director of the climate science center at Texas Tech University. Blackburn, she says, “understands, perhaps better than any, the tension between the old, soon-to-be-outdated sources of energy that power our economy and the new, clean sources that we hope will continue to power it for decades to come.”

Take all of Blackburn’s Texas-friendly climate reforms together and you get something he likes to call the Green New Deal for Red States, another in a growing field of “green deals” proposed by lawmakers. A big part of his plan is Texas Coastal Exchange, the latest of many local nonprofits Blackburn has helped found over the years.

The organization, which was granted tax-exempt status in November, asks Houstonians to cover their personal emissions. The price is $20 per ton, and the average Houston family of four creates 27 metric tons of CO₂ each year, excluding air travel. That works out to $540. The money goes to landowners of coastal wetlands threatened by sea level rise, giving them an incentive to maintain and even expand marshes that are very effective in pulling carbon from the air.

Kirksey, a 160-employee architecture firm in Houston, figured it was responsible for 1,300 to 1,400 metric tons a year. After offsetting about half of its footprint with renewable energy and contributions to local tree planting, the firm decided to make up for the rest, 772 tons, through paying to protect 386 acres of marshland on the nonprofit exchange. “It’s really not just writing a check to make yourself feel good,” says Kirksey President Wes Good. “It’s tangible. It’s local.”

Even as more businesses pay attention to Blackburn, he’s still fighting an uphill battle to get Houston to take climate change as seriously as he does.

So far, donors have bought up just a tiny fraction of the exchange’s almost 6,034 acres of inventory. If even a small percentage of the Houston metro area’s 7 million people paid up, Blackburn points out, miles of coast would be protected.

Meanwhile, some oil executives still sound baffled by the very idea of his Soil Value Exchange. One oilman asked how he was supposed to get his pipes out to ranches. Blackburn laughs, but he’s also clearly frustrated, watching as fossil fuel companies fall into old habits, like contemplating a whole new network of pipelines up and down the coast to support CCUS.

“Somehow we always find a way to disappoint Jim,” Harvey, of Greater Houston Partnership, says ruefully. “But the fact that we perhaps don’t respond as aggressively as we might shouldn’t be interpreted as hostility.”

Blackburn may criticize Houston’s business establishment but he’s not ready to give up on his neighbors. He feels Texans’ mood shifting, and he’s seizing the moment. Giving talks in front of Houston’s wealthiest—at the exclusive River Oaks Country Club, for example—he is getting a different reaction these days. “Five years ago, I was the environmental nut,” he says. “Today, they’re very concerned that I may be absolutely right. There is a bit of horror associated with it.”

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS