By Kevin Crowley

The malaise is largely attributable to the gush of supply from quick-to-drill shale wells. The shale revolution has made the U.S. the world’s biggest producer of oil and natural gas. In 2019 it became a net exporter of crude for the first full month in at least 70 years. Production was at a record 12.9 million barrels per day at the end of November, more than Iraq, Iran, Kuwait and United Arab Emirates combined.

But independent U.S. oil companies have become a victim of their own success, boosting production via debt-fueled drilling campaigns at the expense of their own shareholders, who have waited in vain for sustainable free cash flow. The message from investors to producers in 2020 is a simple one: Stop spending our money.

Shareholder apathy has seen energy slump to just 4.2% of the overall market value of S&P 500 Index at the end of November, a record low. Even the majors, with operations spread around the world, aren’t immune. Exxon Mobil Corp. dropped out of the top 10 companies in the S&P 500 companies for the first time.

“Absolutely capital discipline is the number one priority, said Jeff Wyll, senior energy analyst at Neuberger Berman Group LLC, which has about $333 billion under management. “Deliver on your promises, don’t raise capital expenditures, stay disciplined. It’s that simple.”

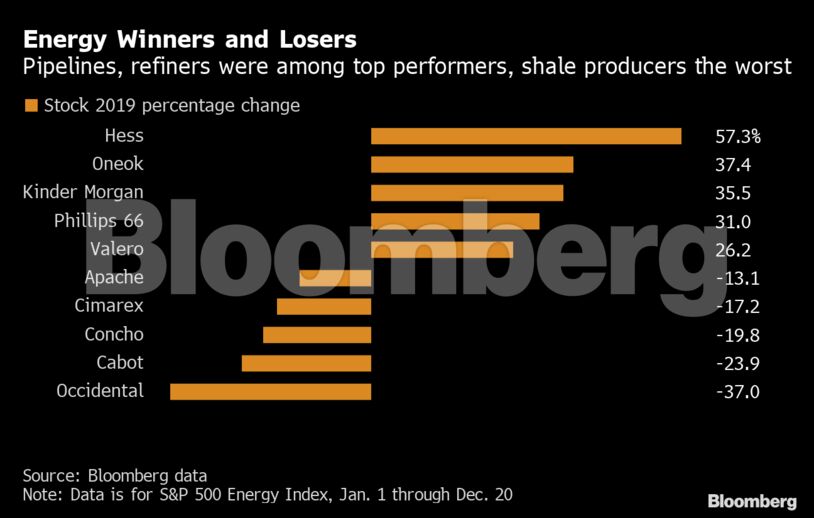

In the broader U.S. energy space, the best performers in 2019 have been pipeline operators, refiners, and companies with big assets outside the shale sector. The worst have been shale-heavy producers, especially those with high levels of debt and spending, or more assets that are more gassy — gas prices are down for a third year.

With energy now such a small share of the broader market, many fund managers are unwilling to devote time to studying individual stocks, according to Jennifer Rowland, an analyst at Edward Jones & Co. Chevron is the go-to stock for energy exposure due to its large index weighting and commitment to financial discipline, she said.

“Pick Chevron, maybe one other, and to heck with the rest of the space,” she said, describing the mindset of energy investors in 2019.

Chevron distinguished itself this year by walking away from its attempt to buy Anadarko Petroleum Corp. rather than top a $37 billion bid from Occidental Petroleum Corp. It was a move unthinkable during the boom times for Big Oil: One of the world’s largest companies allowing itself to be outbid by an independent only a fifth of its size.

But in an environment where investors prize capital discipline above all else, that decision has so far been vindicated. Chevron burnished its reputation for financial prudence, pocketed a $1 billion break-up fee and later boosted its share buyback plan by 25%. Occidental, meanwhile, has plunged to a record low and was forced to cut capital spending and sell assets to pare down the debt incurred buying Anadarko.

“The consolidators so far have been punished by the market,” Wyll said. “Chevron is seen as a leader on the capital discipline front right now.”

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

Trump Is Scaring Republicans Away From Saving the Planet