By Liam Denning

Chevron joins the ranks of Exxon Mobil Corp. — which paid $35 billion for XTO Energy Inc. less than a year before the Atlas deal and has been haunted by it ever since — and ConocoPhillips, which bought Rockies gas producer Burlington Resources Inc. way back in 2006 for $36 billion and then wrote most of that off in 2008.

But there is far more to this than just mistimed forays into the graveyard of optimism that is the U.S. natural gas market — and not just for Chevron.

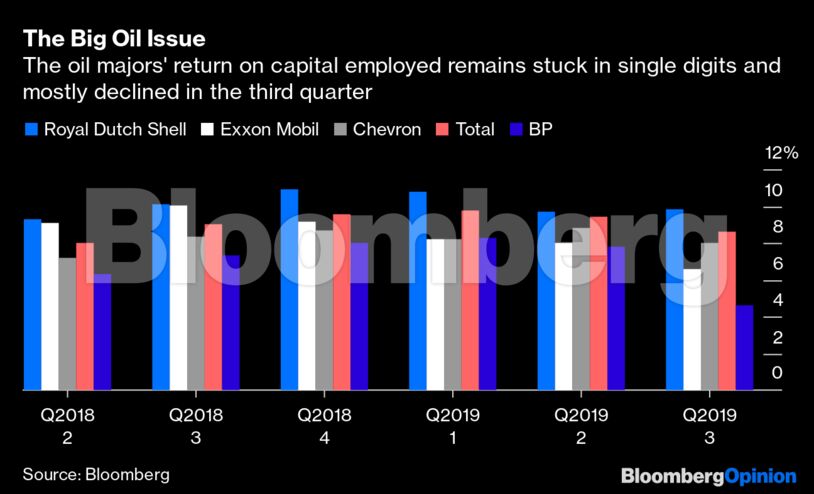

Big Oil just had a forgettable earnings season. Chevron announced cost overruns on the giant Tengiz expansion project in Kazakhstan. Exxon continued borrowing to cover its dividend. Across the pond, BP Plc and Royal Dutch Shell Plc flubbed resetting expectations on dividends and buybacks. What ties all of these together are weak returns on capital.

Chevron’s problems in Kazakhstan are echoed in its impairment of another asset, the Big Foot field in the Gulf of Mexico. This is another mega-project that went awry and, in an era when producers can no longer count on an oil upswing to save the economics, is found wanting. Chevron is also ditching the Kitimat LNG project in Canada that it bought into in 2013.

All this is a particularly sore spot for Chevron given its problems with Australian liquefied natural gas mega-projects earlier this decade. CEO Mike Wirth’s decision to clear the decks seems intended in part to signal that, unlike the experience of his predecessor with Australian LNG development, he will drop big assets that don’t make the cut financially.

Discovering, financing and developing mega-projects is why the supermajors were created at the end of the 1990s. Today, when investors are interested at all, they’re leery of capital outlays, aware the outlook for oil and gas markets is challenged in fundamental ways. So tying up money in big, risky, multi-year ventures is a good way to crush your stock price.

Wirth isn’t abandoning conventional development; Big Foot aside, the Gulf Of Mexico has several new projects in the pipeline, for example. But to offset the drag on returns from the extra spending at Tengiz, he must streamline the rest of the portfolio.

This is the story of the sector writ large. “Too much capital is chasing too few opportunities,” as Doug Terreson of Evercore ISI puts it. Conoco, which remade itself radically after the Burlington debacle, set the tone with its recent analyst day, emphasizing the need to get the industry’s long-standing spending habits under control and focus on returns to win back investors who are free to put their money into other sectors. Chevron’s write-offs and shareholder payouts (38% of cash from operations over the past 12 months) are of a piece with this. While the company has laid out guidance for production to grow by 3% to 4% a year, that is very much subject to the returns on offer. Capital intensity — as in, shrinking it — is what counts.

Chevron’s move throws the spotlight especially on big rival Exxon. While Exxon has taken some impairment against its U.S. gas assets, that represented a small fraction of the XTO purchase. Exxon also sticks out right now for its giant capex budget (bigger than Chevron’s by more than half), leaving no room for buybacks or even to fully cover its dividend.

In the first decade of the supermajors, when peak oil supply was a thing, big projects with big budgets to match were something to boast about. As the second decade draws to an end, only the leanest operators will survive. Chevron won’t be the last oil major to rip off the band-aid, just as we haven’t yet seen the full extent of the inevitable restructurings and consolidation among the smaller E&P companies. On this front, there’s another golden rule: Better to get it done sooner rather than later.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS