“How unprecedented is it? It’s very,” Barclays Plc analyst Eric Beaumont said. “Both sides need to be willing to come to the table.”

Time is fleeting. Cuomo has threatened to revoke National Grid’s license to operate its downstate gas business if it doesn’t have a plan by Nov. 26 to start connecting new customers. The two sides paint starkly different pictures of the problem.

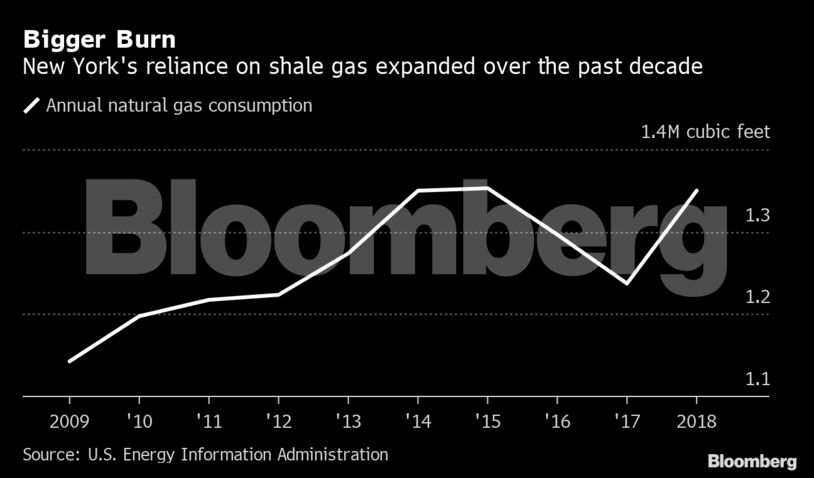

The utility — which provides gas to more than 1.8 million homes and businesses in Brooklyn, Queens and Long Island — says it doesn’t have a choice. Demand for gas is booming. Pipelines are full. Unless the state approves more, there’s not enough gas to serve new customers, the company says.

“We’ve spent the last 10 years looking at the constraints associated with New York state,” National Grid Chief Executive Officer John Pettigrew said on a call with analysts this month.

Cuomo says that’s bogus. In a letter last week, he blasted National Grid, saying its moratorium on new hookups was “either a fabricated device or a lack of competence.” The company, he said, hasn’t done enough to make its system more efficient and encourage conservation.

It’s not easy to sort out who’s right.

New York sits atop rich deposits of gas. But in addition to blocking the pipeline, the state has outlawed fracking, making it all but impossible to produce gas locally. Such moves have crimped supply in the region, Fitch Ratings Inc. analyst Kevin Beicke said.

Yet Karl Rabago of the Pace Energy and Climate Center says Cuomo has a point. There’s already enough wasted gas in the system to accommodate new demand, Rabago said. “We don’t need to force ourselves into the choice of adding more gas or denying people service,” he said.

While Cuomo’s deadline is imminent, it could take months — or even a year — to actually revoke National Grid’s license and bring in another utility. A spokeswoman for the governor, Dani Lever, said the state has several tacks it could take, including opening a case before the state’s Public Service Commission. She declined to discuss any legal strategy in detail.

“I have trouble believing they’re going to lose their license,” Barclays’s Beaumont said. Moody’s Investors Service also said in a note Monday that was unlikely Cuomo would follow through with the threat.

In the meantime, companies including the Samanea Group are caught in the crossfire. The Singapore-based developer is in the midst of renovating a shopping mall in Westbury, Long Island. But the project can’t attract restaurants if it can’t get gas.

“This has really stalled our progress,” said Dave Ackerman, a marketing director for Samanea. “If this was electricity that wasn’t available, people would be up in arms.”

The impasse is rooted in frustrated efforts by Williams Cos. and others to build or expand pipelines that ship gas to the Northeast from shale basins in Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia. The New York State Department of Environmental Conservation denied a key permit for Williams’s project in April 2018. It blocked it again in May, saying the line, which would run under New York Bay, threatens water quality and seabeds.

Two days later, National Grid announced it wouldn’t process any new applications for gas service until the pipeline was approved. A second utility, Consolidated Edison Inc., imposed its own moratorium in Westchester County, north of Manhattan. But the company, whose ban hasn’t impacted development on the same scale as the one in Brooklyn and Queens, hasn’t drawn the same ire from Cuomo.

Gas plays a complex role in fighting global warming. It emits far less carbon-dioxide than coal or heating oil. And because fracking has made it so cheap, the fuel has helped force more than 500 coal plants out of businesses, driving down power-sector emissions about 25% in a decade. But because gas contains methane — one of the most potent drivers of climate change — environmentalists warn its continued use endangers the planet.

The problem is there aren’t affordable alternatives. While an increasing number of Americans are using electricity to heat their homes, it’s expensive in colder climates.

“There’s a generalized belief out there that new fossil fuel infrastructure slows down the transition to a greener energy mix,” said David Spence, a University of Texas professor who focuses on energy regulation. “At the same time, people seem to want natural gas in their homes.”

National Grid has said it’s “confident” it can resolve its dispute with Cuomo.

The clock is ticking.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS

COMMENTARY: Trump’s Big Bill Shrinks America’s Energy Future – Cyran