By Brian Wingfield and Julian Lee

Copying from Iran’s own playbook, at least 20 ships turned off their transponders while passing through the strait this month, tanker-tracking data compiled by Bloomberg show. Others appear to have slightly altered their routes once inside the Persian Gulf, sailing closer than usual to Saudi Arabia’s coast en route to ports in Kuwait or Iraq.

Before the latest increase in tensions with Iran, ships were more consistent about signaling their positions as they passed through a waterway that handles a third of seaborne petroleum. Once inside the Gulf, shipping routes took them fairly close to the Iranian coast, skirting the offshore South Pars/North gas field shared by Iran and Qatar. Most still do, but a growing number appear to be trying something new.

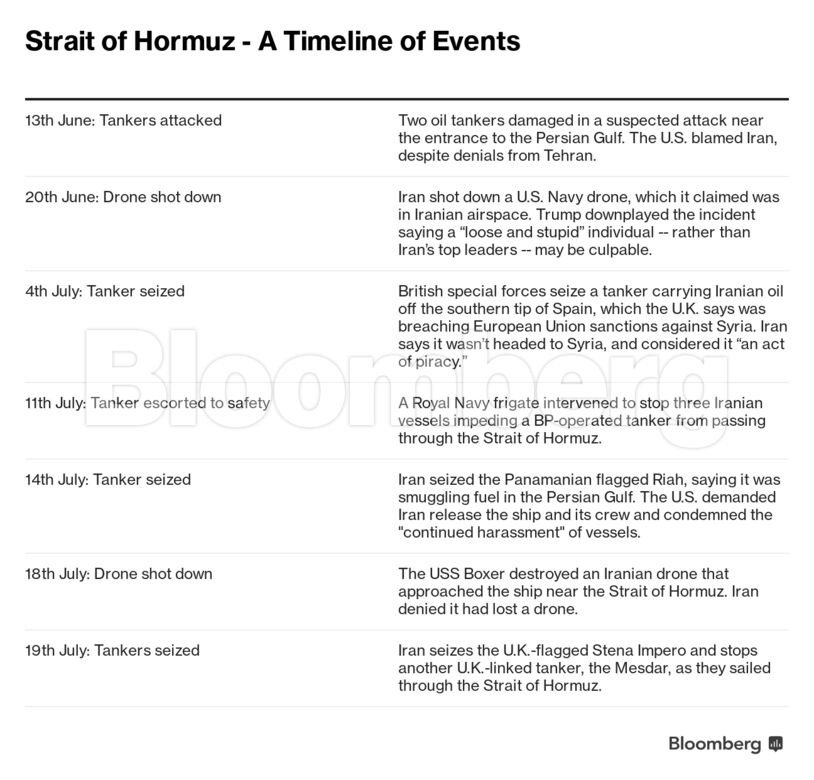

It’s little surprise that ships are doing everything possible to minimize risk. The Gulf region has witnessed a spate of vessel attacks, tanker seizures and drone shoot-downs since May, all against the backdrop of U.S. sanctions aimed at crippling Iran. War-risk insurance soared for tanker owners seeking to load cargoes in the region.

Two British warships are now situated in the waters around Hormuz where they were recently escorting the nation’s ships. The U.S. 5th Fleet also permanently operates in the region. On Wednesday, the Norwegian Maritime Authority advised the country’s flagged vessels to minimize transit time in Iran’s territorial waters. Tanker captains have become increasingly nervous about the risks of getting caught up in the conflict.

See QuickTake on the Strait of Hormuz

At least 12 vessels loaded in Saudi Arabia and shut off their transponders while passing through the strait within the past month. They include the supertanker Kahla, which turned off its signal on July 20 before passing through the strait. It reappeared two days later on the other side of the waterway.

Likewise, at least eight vessels that loaded in Iraq and Kuwait went dark while leaving the Strait of Hormuz. A vessel shipping from the U.A.E. also dropped off tracking systems.

The apparent shutdown of signals coincides with a slew of disruptions in the region. On July 11, the Royal Navy intervened to prevent Iran from impeding a tanker operated by BP Plc from passing through Hormuz. Three days later, Iran seized a Panama-flagged vessel. On July 19, Iranian forces took control of a British-flagged tanker in retaliation for similar action by U.K. authorities. The vessel, the Stena Impero, remains impounded.

Ships go dark when they want to avoid prying eyes — Iranian vessels have been doing it on and off for years because of sanctions that penalized buyers of the nation’s oil. Tankers occasionally turn off their signals when rounding the Arabian peninsula, near flash points in Yemen. This doesn’t make vessels invisible or hide them from radar, though it does make their movements harder to track.

In addition to the signal losses, ships are starting to steer clear as Hormuz increasingly becomes a riskier area. British-flagged tankers have fled the region, and BP is no longer sending its ships and crews through the strait. Some tanker owners have been avoiding sending their ships to the Middle East’s main refueling hub — Fujairah on the eastern side of the United Arab Emirates — due to the perceived threat to commercial vessels.

Al Riqqa, Dar Salwa and Al Funtas are among tankers that stayed relatively close to the Saudi side of the Persian Gulf while en route to Kuwait earlier this month. In addition, at least four ships — the Jaladi, Wafrah, Ghazal and Safaniyah — steered closer to the U.A.E. than usual while passing through Hormuz. It’s not known whether the unusual movements were a response to the mounting tensions or for other reasons.

Share This:

CDN NEWS |

CDN NEWS |  US NEWS

US NEWS